I have long been a supporter of California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS). The LCFS is the leading example of a Clean Fuel Standard, an approach to transportation fuel policy that holds oil refiners accountable to reduce the carbon intensity (CI) of transportation fuels. The CI is determined through a lifecycle analysis of the global warming pollution associated with the production and use of gasoline, diesel, biofuels, electricity, or other alternative fuels. Oil refiners comply with the LCFS by blending cleaner alternative fuels into the gasoline and diesel they sell, and also by buying credits generated by vehicles that don’t use any gasoline or diesel at all, such as electric vehicles (EVs). The LCFS has delivered important benefits to California, including billions of dollars of support for transportation electrification, and has been a model for other states. Oregon and Washington have enacted similar policies, and Minnesota, Illinois, Michigan, New York, and New Mexico have taken up legislation to adopt similar policies. Federal transportation fuel policy would also benefit from a more comprehensive approach that supports electricity, among other alternatives to petroleum and focuses on emissions reductions rather than simply requiring the use of increased volumes of biofuels.

But California’s LCFS has been struggling and is approaching a treacherous precipice. A flood of credits from renewable diesel and manure biomethane have depressed credit prices, undermining the support the LCFS provides for electrification and more scalable low carbon fuels. A rulemaking process is underway to amend the rules of the LCFS including updating the scheduled increases in stringency. The current rules require a 20 percent reduction in the CI of transportation fuels by 2030, which the proposed amendments would change to 30 percent in 2030 and 90 percent in 2045. The California Air Resources Board (CARB) is set to consider the proposed changes on March 21.

Getting this right is important, both for California and to ensure the LCFS remains a workable model for other states and the federal government. When the Board meets in March to update the LCFS, they should place a cap on vegetable-oil based fuels for four major reasons:

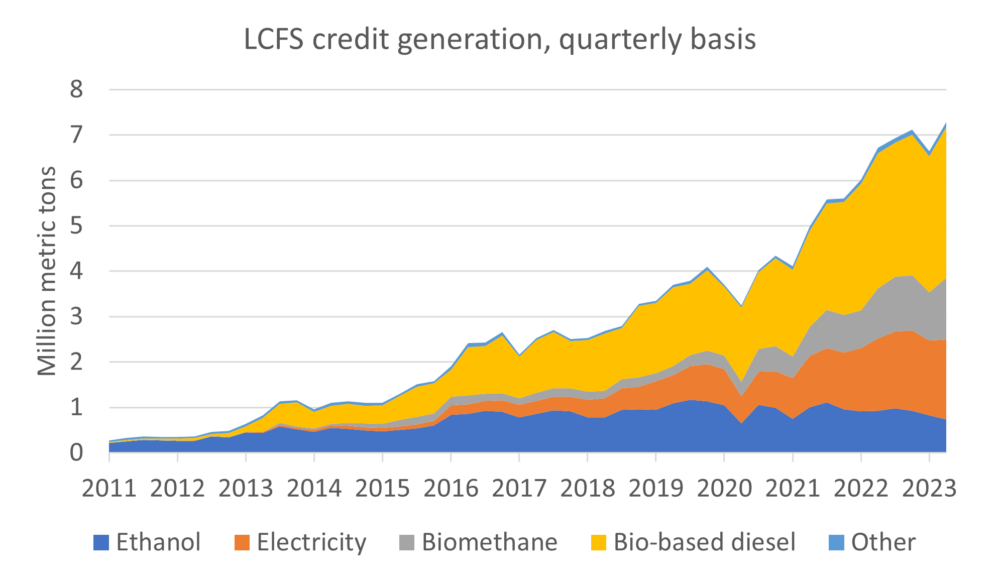

- Broken policies: Counter-productive interactions of the LCFS with federal policy are leading oil companies to redirect most of the bio-based diesel (biodiesel and renewable diesel) they are required to sell in the United States to California, which now consumes more than half of the national supply, even though California consumes only 7 percent of the nation’s overall diesel fuel (bio-based and fossil diesel combined). This is drawing bio-based diesel fuel out of other states and putting California and federal fuel policies into a vicious cycle that is contributing to ever more unsustainable and expensive fuel policies.

- Global hunger and deforestation: Excessive consumption of bio-based diesel fuels has already contributed to the 2022 global food crisis, and is accelerating deforestation caused by increased soybean and palm oil cultivation around the world.

- Gas prices: Without a cap, the flood of bio-based diesel into California will continue, requiring a rapid increase in stringency to stabilize LCFS credit markets, sending 2030 stringency from the 30 percent proposed in the regulation to 34.5 percent or even 39 percent with a commensurate increase in costs for California drivers.

- Credit price stabilization and support for EVs: Limiting the use of vegetable oil-based biofuels, as CARB staff considered in a proposal to cap the use of fuels made from virgin oils, will stabilize LCFS credit markets with less dramatic increases in stringency, supporting a balanced set of clean transportation solutions, including EVs, while reducing costs for California drivers.

This post focuses on the need for a cap on vegetable oil-based fuels, which is one of several necessary reforms to the LCFS. For more information on our position on manure biomethane and other topics, see the feedback we sent Governor Newsom last year.

What broke the LCFS?

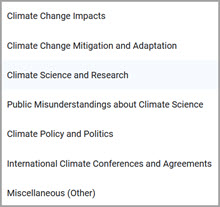

To solve a problem, it is important to understand the root causes. California’s transportation fuels policy creates a market for low carbon fuels, which are tracked using a system of credits and deficits shown in Figure 1 below. The supply of credits from low carbon fuels has been exceeding the requirements of the LCFS, leading to falling credit prices. You might think that low credit prices mean the program is meeting its goals at lower cost than expected, which would be great. Unfortunately, this is far from the truth. More than 60 percent of the credits flooding the program are coming from bio-based diesel and biomethane, crowding out the support the LCFS would otherwise provide to electric cars and trucks to support California’s transition away from combustion fuels.

Figure 1. LCFS credit generation. Source California Air Resources Board.

Figure 1. LCFS credit generation. Source California Air Resources Board.Stabilizing credit prices at a level that supports steady progress (roughly $150 per metric ton) is a key goal of the rulemaking process. Since credit prices are set by the balance of supply and demand, prices could be raised by either restricting the supply of credits or by increasing LCFS stringency to raise demand. During the two years of workshops that preceded the formal proposal, concepts discussed by CARB staff included changes to the rules that would reduce the supply of credits from bio-based diesel and biomethane and increased stringency to increase demand for credits. But the official proposal abandoned any meaningful effort to address supply and focuses almost entirely on increasing stringency.

CARB has proposed increasing the 2030 stringency of the LCFS by 50 percent, from the current requirement of a 20 percent reduction in the carbon intensity in 2030 to a 30 percent reduction in 2030. CARB has also proposed an auto-acceleration mechanism, which could see the 2030 stringency rise to 34.5 percent or 39 percent if the supply of credits continue to substantially exceed demand.

In my feedback over the last 2 years, I argued CARB should cap support for bio-based diesel made from vegetable oil and phase out credits for avoided methane pollution to wind down what has become, in effect, a poorly run offset program. Bio-based diesel and manure biomethane generate a lot more credits than an accurate assessment of their climate benefits would support, and are causing additional problems to boot. Unfortunately, the official proposal ignores the oversupply of low value credits and focuses almost exclusively on increasing demand by accelerating the pace of the program. This won’t work—and will make the LCFS needlessly costly for California drivers, while postponing the needed reforms that would restore the stability of the LCFS. Moreover, absent reform, the LCFS is not a replicable model for other states or the federal government.

Capping the renewable diesel boom

Bio-based diesel refers to two closely related fuels, biodiesel and renewable diesel that are made from vegetable oils and animal fats and blended into diesel fuel. I just posted a detailed article describing the surge in renewable diesel—used mostly in California and made increasingly from soybean oil—that threatens to create major problems in global vegetable oil markets and accelerate tropical deforestation caused by expanding cultivation of soybeans and palm oil.

California may seem like an unlikely driver of deforestation from soybean and palm oil biofuels. The California LCFS has, since its inception, included significant disincentives for the use of crop-based biofuels, including soybean and palm oil-based diesel. Instead, the LCFS encourages the use of fuels made from used cooking oil, animal fats or other secondary fats and oils. For almost a decade, these disincentives effectively kept crop-based diesel fuels out of the California market. However, for reasons explained below, this incentive-based safeguard has become ineffective, and since 2020 California’s bio-based diesel has increasingly been made from soybean oil, some of it sourced directly from South America.

The proposed amendments to the LCFS acknowledge the risks posed by the rising use of soybean oil-based renewable diesel. This reflects concerns raised by many stakeholders, myself included, at LCFS workshops since December 2021 (I submitted technical feedback on this topic six times over the last two years, and coauthored a paper on the subject). The first page of the rulemaking document suggests CARB intends to “[strengthen] guardrails on crop-based fuels to prevent deforestation or other potential adverse impacts.” The proposal considers a cap on the use of fuels made from virgin vegetable oils in Alternative 1, but then rejects it based on flawed arguments addressed below. Instead of a cap, the proposal suggests tracking the chain of custody for crop-based feedstocks, an ineffective approach that will not address the root causes of the problem.

I’ll explain why the cap described in Alternative 1 is the right decision, why the arguments against it are wrong, and why the feedstock tracking proposal is not an adequate safeguard. But first it’s important to understand how the implementation of the LCFS is being distorted by complicated interactions with federal biofuels policy, since this explains the root cause of the renewable diesel problem and points the way to a solution.

The LCFS operates on a playing field shaped by federal policy

If the California LCFS acted without the influence of federal policy, there would be no renewable diesel boom, and there would certainly not be a flood of soybean oil-based diesel. The limited support offered by the LCFS for soybean oil-based fuels would not come close to covering the cost of expensive soybean oil needed to make the fuel. It’s the interaction of the California LCFS with federal policy, particularly the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS), that has led to California’s renewable diesel boom.

The RFS requires oil companies to blend increasing amounts of a few types of biofuels into the gasoline and diesel they sell. In its early years, between 2005 and 2010, the RFS helped launch the massive scaleup of corn ethanol that established 10 percent ethanol as the de facto standard for US gasoline. After 2010, bio-based diesel fuels (biodiesel and renewable diesel) have been the main beneficiary of the RFS.

Bio-based diesel fuels are expensive. Without substantial policy support, there would be little if any bio-based diesel fuel produced or consumed in the United States. Analysis by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the most recent RFS rulemaking finds that more than 90 percent of the costs of complying with the RFS, $7 to $8 billion a year, are associated with bio-based diesel fuels[i]. These costs are spread across all the diesel fuel consumed in the United States, adding 13 to 15 cents per gallon to the cost of diesel fuel in the United States, according to EPA.

The RFS sets national targets, but also includes a system of tradable credits that allow overcompliance in one region (or by one company) to offset undercompliance in another region (or by another company). This flexibility allows for higher levels of biofuel consumption in states with supportive policies to offset lower consumption elsewhere. Economic factors and practical limits on blending keep ethanol and biodiesel widely distributed. In 2020, every state except Alaska blended at least 9.5 percent ethanol into their gasoline versus a US average of 10.3 percent, while 35 states blended at least 2 percent biodiesel into their diesel, versus a US average of 3.8 percent.

Renewable diesel is a different story. Since renewable diesel is a replacement for diesel rather than an additive, there are no practical blending constraints. This has allowed oil companies to meet a rising share of their RFS obligations in California, where the same fuel also provides compliance for the LCFS. In 2022 half of the bio-based diesel consumed in the United States was consumed in California, which accounts for just 12 percent of US population and just 7 percent of the nation’s overall diesel (bio-based and fossil diesel combined). The factors that concentrated half of US bio-based diesel in California are only getting stronger, as more renewable diesel production capacity comes on-line in California, and California raises the targets for the LCFS.

Figure 2: Share of California consumption of US bio-based diesel fuel (biodiesel and renewable diesel) weighted by their RFS compliance value. Source California Air Resources Board, US Energy Information Administration.

Figure 2: Share of California consumption of US bio-based diesel fuel (biodiesel and renewable diesel) weighted by their RFS compliance value. Source California Air Resources Board, US Energy Information Administration.Unless CARB changes course, California is likely to consume well over half of US bio-based diesel, including increasing amounts of soybean oil-based fuel, putting pressure on the EPA to raise RFS targets to unsustainable levels that harm access to food and accelerate deforestation. Concentrating RFS compliance in California reduces oil companies’ compliance costs, but it destabilizes both the RFS and LCFS. It makes no sense for California to consume most of the US supply of bio-based diesel.

Capping vegetable oil-based fuels is the right decision

The CARB rulemaking document called the Initial Statement of Reasons (ISOR) includes consideration of Alternative 1 on pages 88 to 102 that “includes a limit on total credits from diesel fuels or sustainable aviation fuel produced from virgin oil feedstocks.” Because Alternative 1 reduces credit generation, the 2030 stringency is adjusted from 30 percent to 28 percent, but the 2045 stringency remains the same (90 percent). The lower stringency results in lower costs and reduced economic impact of the regulation. The ISOR says, “The macroeconomic impact analysis results shown in Table 23 indicate that Alternative 1 would result in more positive impacts on gross state product (GSP), personal income, employment (Figure 14), output (Figure 15) and private investment when compared to the proposed amendments.” The main reasons CARB gives for rejecting Alternative 1 are the climate and air quality benefits CARB attributes to the higher use of renewable diesel. However, these apparent benefits result from faulty analysis.

According to official analysis from CARB and EPA, soybean oil-based diesel has lower lifecycle carbon emissions than fossil diesel, but this finding is quite uncertain. EPA recently conducted a model comparison exercise that found that the climate benefits attributed to soybean oil biodiesel depend entirely on which model is used to conduct the assessment. While the particular model used by CARB for the LCFS finds that soybean oil biodiesel has lower emissions than fossil diesel, other well-regarded models find that soybean oil biodiesel is more polluting than fossil diesel. But even putting aside this uncertainty, the ISOR overstates the climate benefits of using soybean oil-based fuels because it ignores the fact that use of this fuel in the United States is already mandated by the RFS, so if California uses less, another state will use more. In past rulemakings, CARB accounted for this policy overlap by only including climate benefits that exceed those required by federal law. But in the current rulemaking, CARB ignores the federal requirements, inflating the claimed climate benefits.

The inflated climate benefits attributed to renewable diesel are especially significant because California’s renewable diesel boom has exhausted the supply of low-carbon sources of renewable diesel. Alternative 1 caps fuels made from virgin oils such as soybean oil, which produce few if any climate benefits not already required by the 50 percent emissions reduction requirements of the federal RFS. So Alternative 1 will have little if any real impact on global warming pollution, even putting aside the contested and uncertain benefits of soybean oil-based fuels in general.

The ISOR also attributes health benefits to increased use of renewable diesel in California, especially associated with reduced fine particulate matter, or PM2.5. This is based on a 2011 analysis and ignores a more recent 2021 study prepared for CARB that looks at the NOx and PM from biodiesel emissions in legacy and new technology diesel engines. The key finding is that air quality benefits from older engines are not observed in new technology diesel engines, which are now required in California. This undercuts one of the main justifications offered to reject limits on renewable diesel. Ironically, because renewable diesel does offer PM and NOx emissions in older trucks that are still in use elsewhere in the US, concentrating most of US renewable diesel in California does not help Californians, but it does harm others across the United States.

Finally, the ISOR also claims that Alternative 1 has lower cost effectiveness than the proposed amendments, but this is a direct result of the inflated CO2 and health benefits. A corrected analysis would reduce or eliminate the difference in cost effectiveness.

Without a cap, things could get a lot worse

This ISOR has several deficiencies compared to previous rulemakings, starting with transparency. It is hard to understand precisely how CARB modeled Alternative 1. Based on my current understanding of the information in the proposal, it appears that the total amount of fuels made from oils and fats is projected to peak in 2025 and then to hover at roughly 2 billion gallons a year thereafter[i]. The share of bio-based diesel blend in overall diesel fuel consumption, or blend rate, is assumed to range between 44 and 56 percent through 2035, and then to increase as total diesel fuels consumption falls, as heavy-duty electrification starts to gain traction.

Reality is running well ahead of CARB projections. Bio-based diesel consumption in the first half of 2023 was at 59 percent, a level CARB modeling does not anticipate prior to 2037. I can’t see any reason why bio-based diesel consumption in California would fall while renewable diesel production capacity in California is ramping up and CARB is proposing to substantially raise LCFS stringency. CARB projects total diesel consumption at 3 billion gallons or more until 2035, so actual consumption could be more than 50 percent higher than CARB’s projection if bio-based diesel fully replaces fossil diesel, as a recent study from UC Davis found was 50 percent likely by 2028. If this happens, the extra credit generation beyond what is modelled in the ISOR could trigger the auto acceleration mechanism, pushing 2030 stringency to 34.5 or even 39 percent, with a commensurate increase in costs. Moreover, if all the diesel used in California is bio-based, all of the compliance costs associated with the LCFS will be borne by drivers of gasoline cars.

Alternative 1 described in the ISOR has roughly 25 percent less biobased diesel at the peak in 2025, so roughly 1.5 billion gallons. That is consistent with 2022 consumption of bio-based diesel in California, and since RFS standards are rising gradually, this would result in California consuming a little less than half of the bio-based diesel and related fuels required for RFS compliance in the United States.

The 2 billion gallons of bio-based diesel projected for the ISOR would satisfy about two-thirds of the 2025 RFS requirements, but if actual consumption exceeds the projection, California consumption could push the RFS mandate for bio-based diesel and related fuels into overcompliance. All sorts of weird things would happen if the RFS became non-binding, starting with RFS credit prices falling and the effective cost of renewable diesel available in California rising, with implications for the cost and feasibility of the LCFS[ii]. A non-binding RFS is not a stable long-term situation, for both economic and political reasons. It could also create a lot of turbulence, not just in fuel markets but in food markets for vegetable oil as well.

A vicious cycle of bad fuel policy decisions

My biggest concern is that a feedback loop between California LCFS and the Federal RFS push US consumption of vegetable oil for fuel to ever more unsustainable levels. This feedback loop is influencing fuel policies today and could become a vicious cycle.

Interactions between the LCFS and the RFS have been a major contributor to the renewable diesel boom, which has flooded California with renewable diesel and depressed LCFS credit prices. Increased renewable diesel production capacity to serve the California market was one of the factors cited in EPA’s decision to raise RFS standards for 2022-2025. And even with the higher RFS targets, increased renewable diesel production in and for California has at least temporarily pushed the RFS into overcompliance, sending credit prices down sharply.

If California regulators respond to low credits prices by dramatically increasing the stringency of the LCFS without a workable mechanism to avoid concentrating RFS compliance in the state, it will keep pulling a growing share of US bio-based diesel fuel into California. This puts the Midwestern biodiesel industry under pressure, and puts Midwestern soybean oil producers at a disadvantage compared to used cooking oil imported from as far away as Australia. This will create enormous political pressure on EPA to raise the RFS standards to ensure that they continue to support soybean biodiesel, renewable diesel, and growing consumption of sustainable aviation fuel in states outside of California. The resulting higher RFS standards will increase the use of vegetable oil-based fuels, driving up the cost of the RFS with uncertain climate benefits and very real risks to food markets and deforestation. Meanwhile, higher RFS standards will support ever more vegetable oil-based fuel in California, further diluting the LCFS, and the vicious cycle continues.

This vicious cycle explains why raising LCFS stringency alone will not rebalance supply and demand for LCFS credits. CARB can break this vicious cycle by limiting California’s share of US bio-based diesel consumption to a reasonable level. The proposal described in Alternative 1 to cap virgin oil-based fuels would do the job, while still leaving California as the largest consumer of bio-based diesel in the US. A cap would also leave space in the bio-based diesel market for other states that have or are considering policies like the LCFS.

As I explained in my earlier article on the renewable diesel boom, successful fuels policy in California and the United States requires being realistic about the available resources used to make biofuel. Vegetable oil is an expensive way to make biofuel with limited potential to sustainably increase scale, especially in the short term. A bidding war between the oil companies and people consuming vegetable oil for food already contributed to the recent food crisis, and may do so again. In the longer term, increased use of vegetable oil-based fuels leads to increased palm oil production to replace the soybeans diverted from food markets to make fuel, contributing to deforestation. Capping vegetable oil used for fuel at a reasonable level will encourage fuel producers to look beyond vegetable oil to more scalable feedstocks. A cap will also save California drivers money, by rebalancing supply and demand for LCFS credits without such a steep acceleration in stringency.

The guardrail proposed in the ISOR is inadequate

CARB’s ISOR mentions the risks posed by crop-based fuels, but unfortunately, the proposed guardrail is inadequate. From page 32:

CARB staff are proposing to require pathway holders to track crop-based and forestry-based feedstocks to their point of origin and require independent feedstock certification to ensure feedstocks are not contributing to impacts on other carbon stocks like forests. CARB staff are also proposing to remove palm-derived fuels from eligibility for credit generation, given that palm oil has been demonstrated to have the highest risk of being sourced from deforested areas.

Tracking the chain of custody won’t work because there is more than enough soybean oil produced on existing cropland in the US, Argentina, and Brazil to produce 100 percent of California’s diesel fuel. The problem with chain of custody tracking is that California won’t be tracking the chain of custody of vegetable oils used to replace those diverted from global food markets for consumption in India or China.

As I mentioned in the appendix to my recent post on the renewable diesel boom, the Phillips 66 Rodeo facility is scaling up production of renewable diesel at a converted oil refinery near San Francisco. Phillips 66 filed paperwork recently indicating it plans to produce renewable diesel and other fuels using soybean oil from Argentina. At full capacity, the massive facility would consume 2.5 million metric tons (MMT) of vegetable oil a year. Argentina is the world’s largest exporter of soybean oil, exporting 4-6 MMT of soybean oil in recent years out of total global soybean oil exports of about 12 MMT. This one huge facility could potentially consume about half Argentina’s exports and 20 percent of global exports. To replace soybean oil from Argentina, major vegetable oil importers like India would import more soybean and palm oil that would not be subject to chain of custody tracking.

CARB has long been a leader in biofuel land use change (I served on an expert workgroup on the topic in 2010), so the staff should appreciate the complex and indirect ways demand for biofuel feedstocks can lead to deforestation. It is disappointing to see this obviously inadequate proposal in place of meaningful action to address a real problem. The proposal to remove eligibility for palm oil-based fuels is even more meaningless, given that the land use change values used in the current regulation already effectively do the same thing.

Ironically, the one place chain of custody tracking is needed is for used cooking oil, which the proposal ignores. The LCFS creates a large incentive to pass off virgin palm oil as used cooking oil. And with renewable diesel producers importing used cooking oil from around the globe, extra vigilance is merited.

Capping vegetable oil fuels and investing in alternatives to combustion

The oil industry is in transition. After a brazen display of fossil fuel industry interference at the global climate talks at COP28, it is clear that the only path to a stable climate is phasing out petroleum and other fossil fuels. Biofuels are not made from petroleum, but a realistic assessment of the available resources makes it clear that biofuels can only play a supporting role and must be limited to a sustainable scale to avoid creating more problems than they solve. Vegetable oil is expensive, its availability is limited, and expansion is linked to deforestation, so the large-scale diversion of vegetable oil to fuel production is an especially bad idea. Yet the oil industry has embraced the idea that their existing oil refineries can help solve climate change by tweaking them to process vegetable oil instead of petroleum.

Renewable diesel has recently overtaken biodiesel as the main bio-based diesel fuel used in the United States. Redirecting vegetable oil from biodiesel to renewable diesel does not reduce petroleum use or overall global warming pollution, but it does allow the oil industry to maximize the overlap in state and federal fuel regulations. The predictable next step is to move vegetable oils from renewable diesel production to jet fuel production, claiming generous tax credits while still generating RFS and LCFS credits and trumpeting an innovative new “climate solution.” Shifting the same limited supply of vegetable oil from one fuel to another will not do anything to address climate change, but it does enable misleading hype and greenwashing from the oil industry and airlines suggesting we can address climate change without phasing out combustion. Likewise, shifting more of the US supply of bio-based diesel into California won’t do anything to help the climate, but it is breaking the LCFS.

The oil industry was once the primary opponent of the LCFS, but they have found a way to work the system to their advantage. Oil companies are taking control of the bio-based diesel industry and trumpeting their plans to scale up biodiesel, renewable diesel, and sustainable aviation fuel, despite knowing there is not enough vegetable oil to make the rhetoric reality. The renewable diesel boom is partly a battle for market share as oil companies flush with fossil fuel profits fight to control the largest share of the small but symbolically important market for renewable fuels. But the collateral damage of this clash between the oil giants is not just the stability and viability of fuel policies, but food availability, deforestation, and the prices of food and transportation fuel.

California should modernize the LCFS to align with its goal of transitioning away from combustion to a zero emissions future. A sensible cap on vegetable oil-based fuels will break the vicious cycle between the RFS and the LCFS, make the LCFS less expensive and more effective, and make it easier for other states to adopt and implement LCFS-style policies. It will also help ensure the LCFS doesn’t exacerbate global hunger and deforestation. The board should send the ISOR back to staff and tell them to get this important policy back on track.

[i] While there are a lot of long documents on the CARB rulemaking website, there is not a clear and quantitative description of the various alternatives, which are described inconsistently in different documents. There is no downloadable table of the quantities of fuels and credits associated with the different alternatives, or enough information to reproduce this information using the CATS tool CARB used for modelling fuel projections. In order to clarify what is at stake, I’ll summarize my understanding based on the available documents. In the ISOR CARB projects that bio-based diesel will peak at 2 billion gallons in 2025, fall below 1.8 billion gallons by 2028 and then hover between 1.5 and 1.8 billion gallons thereafter. They also project several hundred million gallons of alternative jet fuel, of which half is made from virgin oils.

[ii] For more on the implications of a non-binding RFS, see Gerveni, M., T. Hubbs and S. Irwin. “Is the U.S. Renewable Fuel Standard in Danger of Going Over a RIN Cliff?” farmdoc daily (13):99, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, May 31, 2023.

[i] US EPA. Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) Program: Standards for 2023–2025 and Other Changes. Regulatory Impact Analysis. Section 10.4.2, specifically table 10..4.2.2-4. Online at nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi?Dockey=P1017OW2.pdf

9 months ago

65

9 months ago

65