Patrick Webster, Author provided

Patrick Webster, Author providedAustralia’s red goshawk once ruled the skies. But now this almighty raptor, affectionately known as The Red, has become our nation’s rarest bird of prey.

Concern for the species prompted our new research. We completed the first comprehensive population assessment of the red goshawk using a dataset of all known records (1978–2020). The results were even worse than expected.

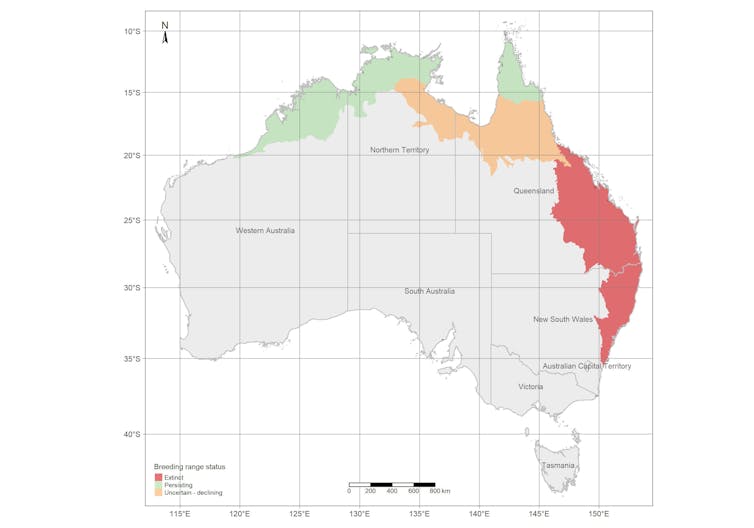

We were shocked to discover The Red had completely disappeared from more than a third (34%) of its range. The species is almost certainly extinct in New South Wales and the southern half of Queensland.

This bird is declining – and probably just barely hanging on – in a further 30% of its range, spanning northern Queensland from the Gulf to the Wet Tropics. The rest of northern Australia is the last stronghold for the species.

Although nationally listed as vulnerable, we argue this species requires urgent uplisting to endangered. High priority must be given to conservation action now, before it’s too late.

Adult female red goshawk with kookaburra prey.

Chris MacColl

Adult female red goshawk with kookaburra prey.

Chris MacColl

A striking bird of prey

The red goshawk (Erythrotriorchis radiatus) is an evolutionary oddity, with no near relatives in this country. It is a top predator, with rainbow lorikeets, sulphur-crested cockatoos, and blue-winged kookaburras its preferred quarry.

Remarkably, the average female is nearly twice the size of the average male, with this relative size difference making it one of the most dimorphic raptors in the world.

This striking bird first came to the attention of Western scientists around 1790, when a specimen was found nailed to an early settler’s hut near Botany Bay.

Since then, it has captivated birdwatchers with its rich rufous (red) plumage, sharp gaze, and immense feet and talons.

Historically, it was found along Australia’s eastern and northern coastal fringe, from Sydney, north to Cape York Peninsula, and across to the Kimberley region of Western Australia. But over the years, keen observers noticed their occasional glimpses of this almighty hawk became rarer. Then suddenly people were no longer seeing them, in certain regions.

Slipping towards extinction

Recording the extinction and ongoing loss of the red goshawk over two thirds of its known range in our lifetime was shocking.

Map showing assessment of the red goshawk’s breeding status across its range.

Chris MacColl, Author provided

Map showing assessment of the red goshawk’s breeding status across its range.

Chris MacColl, Author provided

While the destruction of habitat through land clearing, which is still rampant in both New South Wales and Queensland, is a key reason for this loss, other factors must be at play.

We know that degraded forests, like those that are logged or suffer from inappropriate fire regimes, lose many of their species, particularly those higher up the food chain.

However, this doesn’t aptly describe the loss of red goshawk from seemingly large areas of intact habitat, such as Shoalwater Bay or Conondale National Park.

More research is needed to unpick why this species has disappeared so quickly and over such an immense area. Current efforts focus on potential disease threats, poor breeding, low juvenile survival rates, and developing a better understanding of how they use the Australian landscape.

The Red’s last refuge

Our research reveals northern Australia is the last stronghold for this species. Cape York Peninsula supports the last known breeding population in Queensland. The Top End, Tiwi Islands, and Kimberley regions also sustain vital breeding populations.

This is unsurprising given northern Australia supports the world’s largest intact tropical savanna ecosystem. Yet, despite limited broad scale habitat loss to date, these northern savannas are under threat from inappropriate fire regimes, weeds, cattle, and the onset of climate change. These threats can interact and compound one another, posing increasingly complex challenges for land managers trying to save species like the red goshawk.

For example, the fire-intensive gamba grass, an invasive weed, is spread by livestock. Climate change may extend the fire season, through lengthier dry spells. Hot treetop fires incinerate nests and the chicks inside them. The intensity and seasonality of storms is also increasing, as well as thermal extremes, threatening young during the nesting season.

Two small red goshawk nestlings, the maximum this species can have.

Chris MacColl

Two small red goshawk nestlings, the maximum this species can have.

Chris MacColl

Tropical savannas may be increasingly compromised through large scale vegetation clearing and fragmentation. Preparing land for crops such as cotton or mines for minerals such as bauxite can remove big swathes of habitat. Efforts to obtain other natural resources such as timber and gas also fragment otherwise intact landscapes.

Land clearing remains rife in Queensland, undermining efforts to conserve wildlife and reduce carbon emissions.

Kerry Trapnell/The Wilderness Society

Land clearing remains rife in Queensland, undermining efforts to conserve wildlife and reduce carbon emissions.

Kerry Trapnell/The Wilderness Society

The Red deserves better protection

Australia is blessed with unique bird life. Nearly half of our birds are found nowhere else on Earth.

But the nation’s rarest bird of prey is in trouble. The red goshawk deserves better protection. At the very least, the species needs to be uplisted from vulnerable to endangered by the federal government. This will more accurately reflect current extinction risk and prioritise conservation action. And there’s no time to waste, because red goshawk habitat continues to be cleared – permission was granted to clear a total of 15,689 hectares of red goshawk habitat between 2000 and 2015, which is more than any other threatened species had to contend with.

The Red needs to be recognised as a flagship species for northern Australia, to promote conservation of its remaining habitat. Intervention would benefit many other threatened species, because what’s good for them is good for many others. In this way, the red goshawk is one of the most cost-effective ‘umbrella species’ for conservation action.

To secure the longterm survival of this beautiful bird, we need better protection across the tropical north, expanding both Indigenous Protected Areas and national parks. These areas can be managed directly for conservation, but working with the agricultural and extractive industry is also critical. Low numbers of red goshawks are distributed across a vast area, covering multiple tenures, so all parties need to work together if this species is to persist in the north.

We must not repeat past mistakes and allow habitat in the tropical north to be fragmented, rendering the landscape unable to support native predators like the red goshawk. This means rigorously assessing developments and implementing protections commensurate with the large areas that The Red requires.

If we can’t look after such an ecologically important, charismatic, and iconic species such as The Red, what hope do we have for Australia’s many other threatened species?

Christopher MacColl receives funding and support from Rio Tinto Weipa, the Australian Wildlife Conservancy, the Queensland Department of Environment and Sciences, and the University of Queensland.

James Watson has received funding from the Australian Research Council and National Environmental Science Program and receives funding from South Australia's Department of Environment and Water. He serves on scientific committees for Bush Heritage Australia, SUBAK Australia, BirdLife Australia and has a long-term scientific relationship with the Wildlife Conservation Society. He serves on the Queensland Government's Land Restoration Fund's Investment Panel.

1 year ago

68

1 year ago

68