Yam daisies on the left, cattle on the right Cutting out the cattle, Kangatong/Eugene Von Guerard, 1856 , CC BY-SA

Yam daisies on the left, cattle on the right Cutting out the cattle, Kangatong/Eugene Von Guerard, 1856 , CC BY-SAFirst Nations readers are advised this article contains references to colonial violence against First Nations people.

In 1788 the First Fleet brought two bulls and four cows from the Cape of Good Hope and put them on grass on Bennelong Point, where Sydney Opera House is now. But there wasn’t much grass, and it wasn’t much good, so the cattle took off. Seven years later they were found 65 kilometres southwest, on the Cowpastures near Camden, a flourishing herd. By 1820 they were supporting an abattoir and a couple of tanneries.

The cows had found land that was deliberately made for grazing animals – kangaroos. In small patches and on extensive plains, Dharawal managers had performed cool burns to promote rich grass near water. When the cattle found this grass, they stayed.

It was the start of dispossession. Grazing animals trod on or ate the staple tubers such as murnong, on which local groups relied. These grew in rich beds, but were easily trampled. As colonists moved inland, they took Aboriginal land used for growing grain and ran sheep or cattle on it.

The effects of this upheaval are still with us today.

The Cowpastures at Camden were covered with grass for a reason.

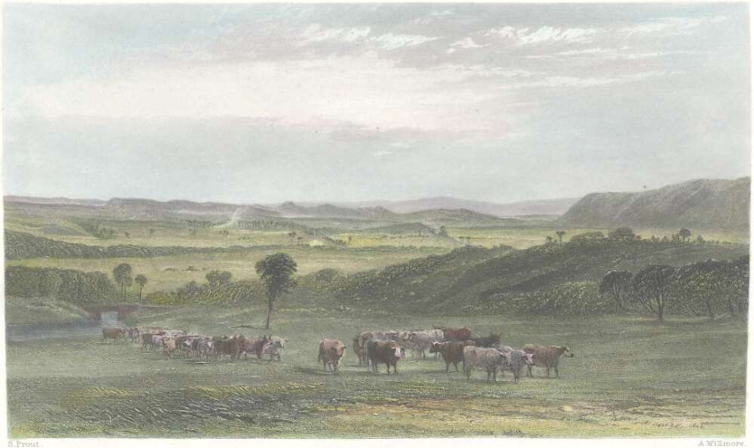

Arthur Willmore, The cow pastures, New South Wales. 1874, CC BY

The Cowpastures at Camden were covered with grass for a reason.

Arthur Willmore, The cow pastures, New South Wales. 1874, CC BY

Without fire, the trees took over

The newcomers who took the Camden country tried to keep it open, without scrub. There, John and Elizabeth Macarthur developed the Australian merino sheep. But they did not understand fire, and the bush got away. As early as 1817, the Macarthurs’ land “had become crowded – choked up in many places by thickets of saplings and large thorn bushes [Bursaria spinosa] and the sweet natural herbage had for the most part been replaced by coarse wiry grasses which grew uncropped”.

In 1848, Thomas Mitchell observed the effects:

The omission of the annual periodical burning by the natives (sic), of the grass and young saplings, has already produced in the open forest lands nearest to Sydney, thick forests of young trees, where, formerly, a man might gallop without impediment, and see whole miles before him. Kangaroos are no longer to be seen there; the grass is choked by underwood.

On good grass, stock fed themselves – they needed only shepherds or stockmen – but European crops grew reluctantly on Sydney sandstone. In 1789, English farmer James Ruse grew corn on better land at Rose Hill near Parramatta, but it still yielded poorly.

In 1794, Ruse sold his block and joined the settlers crowding the rich flats of the Hawkesbury River. Here, he produced the first successful wheat crop.

Soon, corn, English wet wheat and barley were supplying government stores and the Sydney market.

On those Hawkesbury flats, Dharug people had long grown a key staple: tubers. They could not afford to lose the land. They gave some up, but the settlers wanted it all. In 1794, guerilla war broke out. It lasted 22 years – Australia’s longest war – until in 1816 British soldiers finally broke Dharug resistance.

Tubers and grain

Unlike the newcomers, the Dharug rarely ate grain. They preferred tubers. This was common – wherever it was wet enough, people across Australia relied on tubers, notably warran (Dioscorea hastifolia) in the southwest, and the yam daisy, murnong (Microseris lanceolata) in the southeast.

Women regularly dug over tuber fields to make the soil crumbly, and replanted tuber tops for the next harvest. For mile after mile where they had worked, the ground looked ploughed. At Sunbury, near Melbourne, Isaac Batey, a gardener in England, saw a slope of:

rich basaltic clay, evidently well fitted for the production of myrnongs. On the spot are numerous mounds with short spaces between each, and as all these are at right angles to the ridge’s slope, it is conclusive evidence that they were the work of human hands extending over a long series of years.

Yam daisy tubers were a staple for many groups in the south-east.

Shutterstock

Yam daisy tubers were a staple for many groups in the south-east.

Shutterstock

In country too dry for tubers – most of Australia – people grew grain, notably native millet (Panicum decompositum). They chose land near water, burned the ground, spread seed, blocked channels to spread water, watched the seasons to know when to return, reaped the crop by pulling or stripping with stone knives, dried, threshed and winnowed the grain, and stored it in skin bags or ground it into flour.

Native millet (Panicum decompositum) grows happily across most of the arid interior. It was a vital foodstuff.

Harry Rose/Flickr, CC BY-ND

Native millet (Panicum decompositum) grows happily across most of the arid interior. It was a vital foodstuff.

Harry Rose/Flickr, CC BY-ND

On the Narran River, northwest of Lightning Ridge, the explorer and surveyor Thomas Mitchell observed in 1848:

Dry heaps of this grass, that had been pulled expressly for the purpose of gathering the seed, lay along our path for many miles. I counted nine miles along the river, in which we rode through this grass only, reaching to our saddle-girths.

Dispossession and reversal

Even allowing for the modern expansion of irrigation in the north, people probably farmed more of Australia in 1788 than we do now.

But we don’t crop the widespread grainlands of the arid interior. We leave them to cattle or camels. Our crops largely grow on tuber country, so a great many tubers have diminished or disappeared. How people use the land has essentially reversed since 1788, based on my research into the subject.

This upended the lives of many species. It let inland birds such as galahs, crested pigeons, and later, little corellas, expand their range. When Europeans arrived, galahs were typically inland birds. Now they’re common from coast to coast. What changed? My research suggests it was colonisation. Galahs feed on the ground. To get at tall inland grasses, they relied on Aboriginal grain cropping before contact. Afterwards, introduced stock shook or trampled grass – and expanded the galah’s range.

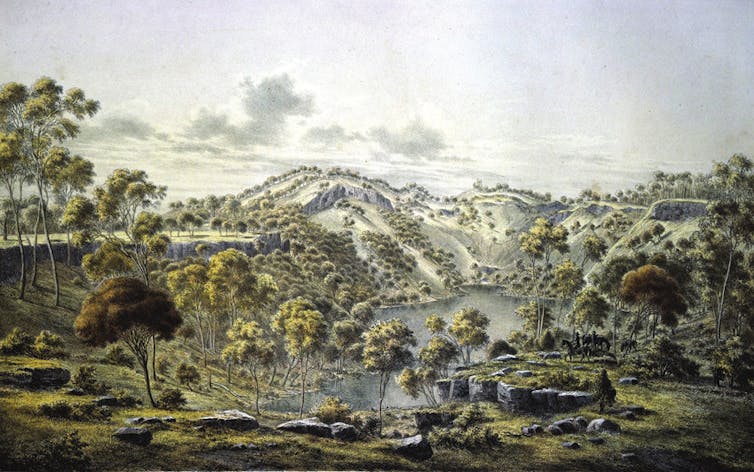

Famed colonial painter Eugene von Guerard captured traditionally managed parkland in many paintings.

The crater of Mt Eccles west from Mt Napier, 1856, CC BY

Famed colonial painter Eugene von Guerard captured traditionally managed parkland in many paintings.

The crater of Mt Eccles west from Mt Napier, 1856, CC BY

But ground-dwelling small and medium-sized mammals and birds declined. Dozens of species became extinct or endangered. The toolache wallaby was gone in less than a century. The lesser stick-nest rat and the paradise parrot disappeared not long after newcomers, their stock, and new predators like cats and foxes invaded their habitats. Today, even the koala is endangered.

Those who had cared for these species – the people of 1788 and after – were devastated by invasion. It’s possible they had more war dead than white Australia’s 103,000 in all its wars.

Survivors were commonly driven or taken from their country, and the land they managed so carefully was made a resource to exploit, or left to burn randomly.

So much was lost. Gone are the stories, the dances, the paintings, the languages of ten thousand campfires, gone knowledge of land, sea and sky, the skill to care for every habitat, to grow local crops and husband native animals, to feel truly at home.

Read more: The biggest estate on earth: how Aborigines made Australia

Bill Gammage does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

1 year ago

57

1 year ago

57