“Is California still in a drought?” is the single most-asked question I hear as someone working daily with water science, advocacy, and policy in California. That question will arise again on April 3 as water officials carry out the season’s final snow survey.

My answer as an advocate is the drought won’t end until everyone in California has access to drinking water. We must recognize that drought impacts and recovery are not experienced uniformly across the state. While some regions may recover faster, others, particularly disadvantaged communities, often face prolonged water scarcity and compromised water quality. These disparities highlight the need for a comprehensive and equitable approach to water management that prioritizes the most vulnerable populations and ensures that every person in the state can benefit from the state’s efforts to fulfill the Human Right to Water.

My answer as a hydrologist is there are different types of droughts to consider. If we’re talking about California’s meteorological drought (based solely on precipitation), I say the drought has likely ended–for now–but we need to advance with caution, as history and climate change tell us that drought periods will return. But if we’re talking about whether the hydrological drought (based on streamflow and soil moisture) is over, we need even more caution, because nearly 45% of California is still abnormally dry.

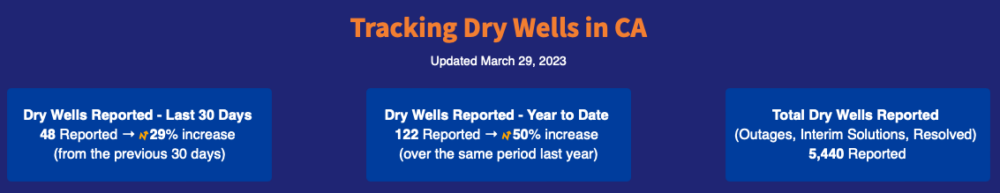

My answer regarding agricultural and ecological droughts is a bit more complicated, as farmers and environmentalists alike continue to advocate for more water to be allocated to their causes, making it evident that our current and projected water supply is still insufficient. Further complicating matters, even with the rain we have had, there are more than 100 reports of wells going dry since the start of 2023 (Figure 1), highlighting that California’s groundwater drought and socioeconomic drought certainly haven’t ended.

Figure 1. There are more than 100 reports of wells going dry since the beginning of the year. That is a 50% increase over the same period last year despite the recent precipitation. Source.

Figure 1. There are more than 100 reports of wells going dry since the beginning of the year. That is a 50% increase over the same period last year despite the recent precipitation. Source.And my answer as someone involved in policy analysis is, unfortunately, in California, the drought is no longer a matter of how much precipitation the state gets but rather how much water it uses. Despite mandatory conservation efforts and more efficient technologies, total water use in the state has barely changed since 1960.

The ongoing megadrought that has afflicted California since 2000 has caused profound challenges for people, agriculture, and ecosystems throughout the state. This megadrought, on top of industrial agriculture’s 100-year history of groundwater overexploitation, particularly in the San Joaquin Valley, has led to land subsidence, reduced surface water, diminished water quality, and low groundwater levels that will take more than one year with above-average precipitation to heal.

The snowpack alleviates some drought conditions, but worsens flooding concerns

Having over twice the average snowpack in the Sierras this year is an opportunity to benefit communities, farmers, and the environment. The increased snowpack is a natural form of water storage that gradually releases water during the spring and summer and fills rivers, lakes, and reservoirs. Some of that excess water is being used to partially recharge groundwater aquifers and serve as water reserves for future droughts. The increased snowmelt could improve the health of rivers and wetlands, supporting the restoration of ecosystems that have been negatively impacted by years of drought and water diversions. The snowmelt going into reservoirs could even help with hydropower production as California transitions towards a more sustainable energy future.

However, while the recent surge in snowpack in the Sierras has temporarily reduced the strain on the state’s water deficit and drought emergencies, it is also unfolding its own set of complications. There is almost twice as much snowpack in the Northern Sierra than average for this time of the year, more than two times in the Central Sierra, and almost three times more than average in the Southern Sierra (Figure 2). Rapid snowmelt this spring and summer could mean more flooding, especially if it coincides with more heavy rain and high temperatures. The increased volume of water may cause rivers, dams, and levees to overflow, inundating nearby communities and farmland.

Figure 2. Snow Water Equivalent in California Sierra Nevada. Data provided by the California Cooperative Snow Survey.

Figure 2. Snow Water Equivalent in California Sierra Nevada. Data provided by the California Cooperative Snow Survey.The lives of people in communities like Planada, Allensworth, and Pajaro already have been turned upside down this year by relentless floods ravaging their communities. The devastation is especially heartbreaking for undocumented immigrants who already grapple with constant fear of exposure and deportation, further compounding their emotional distress. In the face of adversity, these communities have shown remarkable solidarity, extending a helping hand to one another.

Flooding has also affected farmers who have lost part of their crop production. From stone fruits affected by hail in the San Joaquin Valley to almonds affected by cold and wind in the Sacramento Valley and strawberries damaged by floods in the Salinas Valley, the extreme weather has had a profound impact on the agricultural sector. Farmers in these areas are grappling with financial losses and mounting challenges. Small- and medium-sized family farms, in particular, often have fewer resources to sustain damages and don’t have the luxury to prepare for the next growing season.

Drought and flooding amplify farmworkers’ inequities

The same floods affecting agriculture and communities throughout the Central Valley also are disturbing the lives of thousands of farmworker families who rely on agricultural jobs as their primary source of income, exacerbating the inequities they experience during the dry and extreme heat season. With fields submerged and crops damaged during recent storms, work opportunities have become scarce, leading to significant wage losses and financial instability.

While some farmers may receive crop insurance to offset their losses, these compensations do not extend to farmworkers, who often live paycheck to paycheck and now struggle even more to afford basic needs like food, housing, and healthcare. Additionally, the displacement of families due to flooding can result in children missing school and experiencing educational disruptions. The psychological impact of such traumatic events should not be underestimated as families cope with uncertainty, stress, and the prospect of rebuilding their lives.

Farmworkers are predominantly from immigrant communities and they often face additional barriers in accessing support services or government assistance due to language barriers, immigration status, or lack of knowledge about available resources. These challenges exacerbate the vulnerability of farmworkers and their families in the face of these disasters, further highlighting the need for inclusive and comprehensive support systems to mitigate the ongoing crisis.

Unfortunately, the end of the rainy season in April or May won’t mean that communities are safe. All that snow currently in the Sierra will eventually melt and keep stressing water storage and flood management infrastructure.

Even after the floods, there is a multitude of concerns looming over the affected communities, with one of the most pressing issues being the proliferation of mold rendering homes uninhabitable. As the floodwaters recede, they leave behind humid conditions, providing an ideal breeding ground for mold growth within homes and other structures. The presence of mold not only compromises the structural integrity of buildings but also raises serious health risks to residents, particularly those with pre-existing respiratory issues, allergies, and weakened immune systems.

The devastating floods that have affected California this year highlight the urgent need for a coordinated and equitable response to climate-related disasters. To adapt to diverse flood impacts, it is crucial that federal, state, and local governments prioritize health, food, housing, and education for displaced people while their homes are thoroughly dried and cleaned for a safe return. This response must prioritize the needs of affected communities, particularly farmworkers who face disproportionate impacts and barriers to accessing support.

1 year ago

67

1 year ago

67