Wildfires across the western United States and Canada have been worsening. Many factors play a role including climate change, human development and forest management. While there’s consensus around the danger and risks of our current wildfire situation, there is often debate concerning why and how we manage our forests. What’s the relationship between fires and forests? And how does that relationship shape current fire risk?

History of fire and forest management

Humans and fire have shaped the forests of the western US and western Canada since time immemorial. Before European colonization, genocide, and the forced removal of Indigenous communities from their land, fires ignited by Indigenous people and those ignited by lightning regularly burned in these regions, creating a mosaic of forested areas, bare ground, woodlands, and grasslands across the landscape.

This mosaic of vegetation changed how fire would spread and flow across the landscape, moving quickly through flashy fuels like grasses and more slowly through woodier fuels on a forest floor. By regularly clearing out undergrowth, these lower and mixed severity fires helped to reduce the risk of high-severity fires that could kill entire stands of trees or threaten Indigenous communities. While its use varied by region, community, and objective, fire was one of many tools used to manage land, favor specific species over others, and maintain a variety of ecosystem types. Indigenous communities also used fire to protect settled areas, signal over long distances, and attract desirable animals for food.

European colonizers and their descendants, however, fundamentally reshaped the relationship between humans and fire in western North America. Many European settlers brought their own ideas about land management, which considered fire to be damaging to forests and bad for timber supply. They also did not trust Indigenous management practices, despite their adoption by some white settlers. The protection of economic resources like timber supply became paramount, heightening concerns about the impacts of fire.

The idea of fire as exclusively destructive was affirmed by incidents like the the Big Blowup, which burned more than 3 million acres and killed over 75 people in 1910. While this conflagration impacted both settler and tribal lands, tribal lands fared better thanks to millennia of regularly occurring fire. Seizing and purchasing large swaths of land allowed settlers to ban, and in some cases criminalize, intentional burning and implement comprehensive policies of fire suppression, with the goal of extinguishing every fire by 10 am the day after detection.

Consequences of fire exclusion

Suppressing all fires and excluding them from forests profoundly changed the underlying character, structure and composition of western North America’s forests.

In the absence of regularly occurring fire, plants, trees, grasses and other types of vegetation, both live and dead, accumulated in the understory. This increases the risk of high severity fire that can climb into the forest canopy, and kill entire stands of trees.

Forests have also become denser and more continuous, filling in non-forest areas like meadows that were previously maintained by fire. This continuity allows wildfires to spread more quickly across the landscape, since the patches and mosaics of landscapes past can no longer moderate fire behavior.

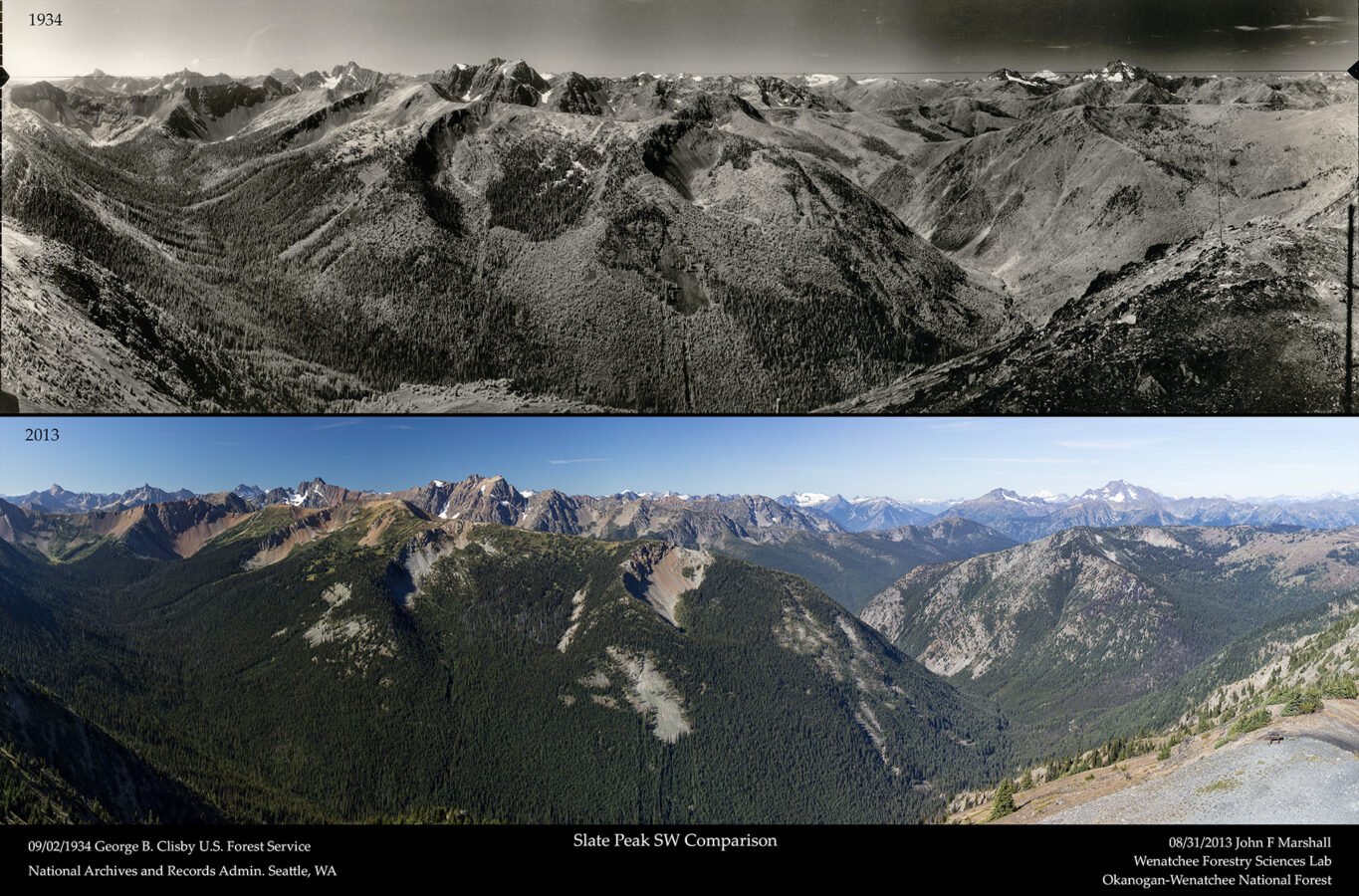

Images of the same landscape taken 79 years apart showing forest in-fill. Image from Hessburg et al 2019.

Images of the same landscape taken 79 years apart showing forest in-fill. Image from Hessburg et al 2019. A focus on timber production also led to the removal of many large, fire-tolerant trees from these landscapes, and reduced the diversity of tree species and ages in forests where logging had occurred. More continuous and densely arranged trees in such forests can easily carry and spread fire, and increase the risk of insect outbreaks like mountain pine beetle, which impacted nearly 40 million acres of forest in British Columbia during an outbreak that peaked in 2004.

Mountain pine beetle killed trees in British Columbia. Image from Government of British Columbia.

Mountain pine beetle killed trees in British Columbia. Image from Government of British Columbia. Climate change as a threat multiplier

The consequences of past forest management continue to reverberate today and are magnified as climate change heats up and dries out western North America’s forests. While the consequences of forest management are readily apparent at the stand and landscape level, the impacts of climate change emerge across regions and metrics.

Using attribution science, which quantifies the contribution of anthropogenic climate change to specific phenomena or the source of emissions that drive climate impacts, we know that climate change is responsible for more than two-thirds of increases in summertime vapor pressure deficit, or VPD, a measure of the drying power of the atmosphere. High VPD conditions dry out vegetation and have led to a near doubling in burned area across forests in the western US since 1984. Climate change has also contributed to an increase in atmospheric drying power at night, which can further burden limited fire-fighting resources.

In addition to climate change, human development into forested areas increases the risk of humans (or our infrastructure) sparking fires. Together, these elements have created dangerous, flammable conditions that threaten the health, livelihoods, and safety of communities across western North America.

Pathways forward

While the legacy of past forest management is clear in western North America’s forests, proactive forest management can also be a tool to address our wildfire problem. Fuel treatments like forest thinning combined with prescribed burns can reduce the risk of crown fire, while allowing wildfires to burn when they can be safely managed can achieve similar objectives. In 2021, many in the wildfire community credited prescribed burns and fuel treatments for changing the Caldor fire’s behavior and helping fire fighters protect nearby communities.

Science-based and Indigenous-led forest management can build and maintain fire resilient landscapes, while using fire-resistant building materials and creating defensible space around homes can reduce risks for communities at the wildland urban interface. Fire will always be a part of these forests, but it doesn’t have to be catastrophic.

1 year ago

73

1 year ago

73