Paul Martinson / Te Papa, CC BY-NC-ND

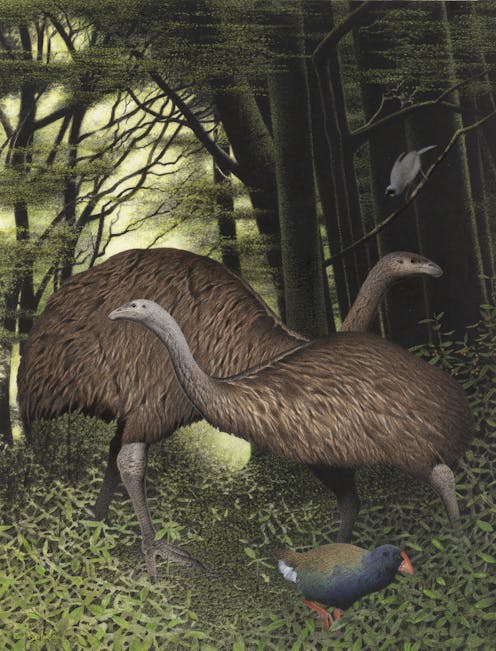

Paul Martinson / Te Papa, CC BY-NC-NDNew Zealand was once home to giant flightless birds called moa. They had grown accustomed to life without predators. So the arrival of humans in the mid-13th century presented a massive – and ultimately insurmountable – challenge to their existence.

Moa were unable to cope with even low levels of hunting by people. All nine species of moa were driven to extinction soon after first contact with humans. These moa populations collapsed and disappeared so swiftly it seemed impossible to trace their declines, until now.

In our new research, we reconstructed patterns of population decline, range contraction and extinction for six moa species. We simulated interactions of moa with humans and their surroundings using hundreds of thousands of scenarios. Then we validated these simulations against information from fossils.

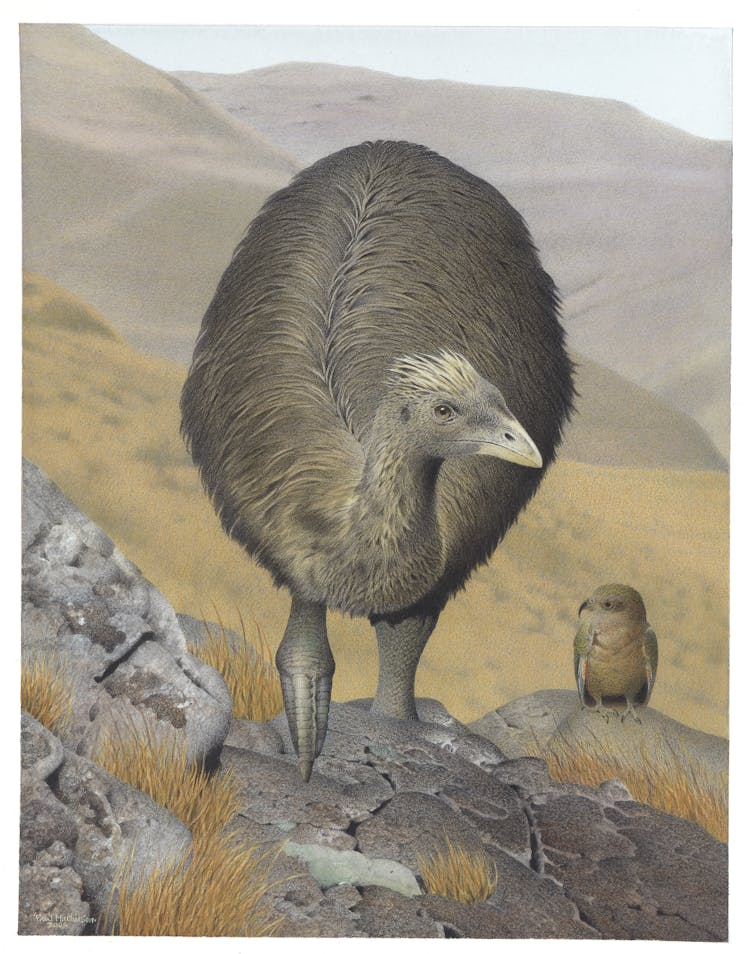

We found all six species collapsed and converged on the cold, isolated mountains of New Zealand’s North and South Islands. These happen to be the same sites where the last of New Zealand’s flightless birds can be found today.

New Zealand’s giant flightless birds, such as the crested moa (Pachyornis australis) shown here, retreated to cold, isolated mountaintops as they headed for extinction.

Paul Martinson / Te Papa, CC BY-NC-ND

New Zealand’s giant flightless birds, such as the crested moa (Pachyornis australis) shown here, retreated to cold, isolated mountaintops as they headed for extinction.

Paul Martinson / Te Papa, CC BY-NC-ND

The Polynesian colonisation of New Zealand

Oceanic islands tend to be hotspots of biodiversity, harbouring some of the most bizarre evolutionary marvels on Earth. They include daisies the size of trees, elephants the size of great Danes, and countless species of flightless birds.

Unfortunately, islands are also hotspots of extinction. This is particularly true for oceanic islands in the Pacific, which were among the last areas on the planet to have been settled and transformed by humanity.

Human expansion across the Pacific began some 4,000 years ago, when people set out on extraordinary sea voyages from Taiwan. They first headed south into the Philippines, and then onto some of the most isolated islands on the planet.

These daring journeys required impressive seafaring vessels and navigational skills to cross thousands of kilometres of open waters.

Migration into central and east Polynesia was the final phase of these ancient voyages. It culminated in the colonisation of the New Zealand Archipelago in the mid-13th century by Polynesians, the ancestors of Māori.

People started fires, hunted animals and introduced invasive species – including Pacific rats. Accordingly, New Zealand’s unique biodiversity was decimated in one of the largest and most rapid collapses of native wildlife in the Pacific.

Moa ate fruit, seeds, leaves and grasses. The North Island giant moa Dinornis novaezealandiae lasted longer than other species.

Paul Martinson / Te Papa, CC BY-NC-ND

Moa ate fruit, seeds, leaves and grasses. The North Island giant moa Dinornis novaezealandiae lasted longer than other species.

Paul Martinson / Te Papa, CC BY-NC-ND

Range collapses and extinctions of moa

Moa disappeared within three centuries of human arrival. But they didn’t all go at once.

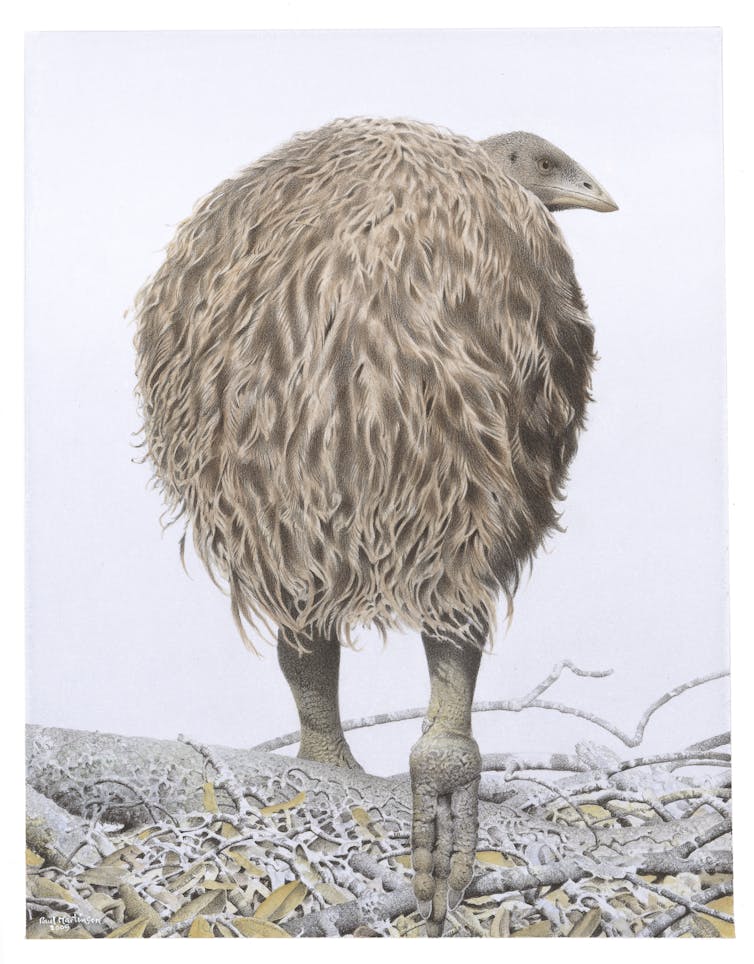

Our research suggests Mantell’s moa went first, within just 100 years. Almost another 100 years would pass before the extinction of any other moa species.

Mantell’s moa was especially vulnerable to extinction because of its slow population growth rate. Unfortunately, even low but sustained harvesting well exceeded the bird’s capacity to reproduce and compensate for these losses.

Other species were slightly more resilient. They benefited from attributes such as higher growth rates, larger ranges, bigger populations or better abilities to live at higher altitudes (far from people).

The stout-legged moa lasted the longest. It finally disappeared some three centuries after human arrival.

Our research suggests all moa disappeared from high-quality lowland habitats first. These were places favoured by people.

The rate of population decline then decreased as you go higher into the mountains and further away from the coastline.

It was previously thought the ranges of species under pressure would contract to their optimal or preferred habitats, where they were most abundant, rather than as far away from people as they could get.

Our research suggests Mantell’s moa (Pachyornis geranoides) was the first moa species hunted to extinction.

Paul Martinson / Te Papa, CC BY-NC-ND

Our research suggests Mantell’s moa (Pachyornis geranoides) was the first moa species hunted to extinction.

Paul Martinson / Te Papa, CC BY-NC-ND

Today’s flightless birds cling to moa refuges

Our research also took a closer look at the distribution of New Zealand’s living flightless birds.

The critically endangered kākāpō.

FeatherStalker Don, Shutterstock

The critically endangered kākāpō.

FeatherStalker Don, Shutterstock

It turns out ancient moa refuges now harbour populations of endangered native flightless birds including the takahē, weka and great spotted kiwi. Moa refuges were also the last mainland habitats for the critically endangered kākāpō.

These sites do not provide optimal habitat for living flightless birds either. Rather, they remain the most isolated and relatively untouched by humanity.

While New Zealand’s remaining flightless birds are no longer being hunted to extinction, threats to their survival still align with human activity.

Habitat loss and impacts of invasive species follows waves of European settlement across New Zealand, which gradually progressed from lowland sites to the less hospitable, cold and mountainous regions.

Efforts to conserve New Zealand’s remaining flightless birds can heed lessons from the ghosts of species past. The sad demise of the moa highlights the immense importance of isolated areas. If we are to prevent future extinctions, we need to protect and preserve these remote, wild places.

Our research also offers a new approach to understanding past extinctions, especially on islands where fossil and archaeological data are limited.

Damien Fordham receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Jamie Wood, Mark V. Lomolino, and Sean Tomlinson do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

3 months ago

47

3 months ago

47