Scientists working for General Motors and Ford Motor Co. knew as early as the 1960s that carbon emissions were warming Earth.

Scientists at two of America's biggest automakers knew as early as the 1960s that car emissions caused climate change, a monthslong investigation by E&E News has found.

The discoveries by General Motors and Ford Motor Co. preceded decades of political lobbying by the two car giants that undermined global attempts to reduce emissions while stalling U.S. efforts to make vehicles cleaner.

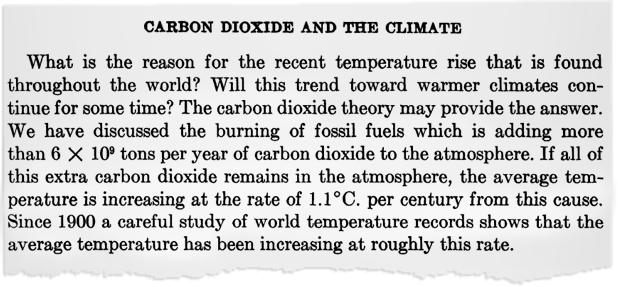

Researchers at both automakers found strong evidence in the 1960s and '70s that human activity was warming the Earth. A primary culprit was the burning of fossil fuels, which released large quantities of heat-trapping gases such as carbon dioxide that could trigger melting of polar ice sheets and other dire consequences.

A GM scientist presented her findings to at least three high-level executives at the company, including a former chairman and CEO. It's unclear whether similar warnings reached the top brass at Ford.

But in the following decades, both manufacturers largely failed to act on the knowledge that their products were heating the planet. Instead of shifting their business models away from fossil fuels, the companies invested heavily in gas-guzzling trucks and SUVs. At the same time, the two carmakers privately donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to groups that cast doubt on the scientific consensus on global warming.

It wasn't until 1996 that GM produced its first commercial electric vehicle, called the EV1. Ford released a compact electric pickup truck in 1998.

More than 50 years after the automakers learned about climate change, the transportation sector is the leading source of planet-warming pollution in the United States. Cars and trucks account for the bulk of those emissions.

This investigation is based on nearly five months of reporting by E&E News, including more than two dozen interviews with former GM and Ford employees, retired auto industry executives, academics, and environmentalists. Many of these details have not previously been reported.

E&E News obtained hundreds of pages of documents on GM's corporate history from the General Motors Heritage Center and Wayne State University in Detroit. Documents on Ford's climate research were unearthed by the Center for International Environmental Law. The Climate Investigations Center provided additional material on both manufacturers.

The investigation reveals striking parallels between two of the country's biggest automakers and Exxon Mobil Corp., one of the world's largest publicly traded oil and gas companies. Exxon privately knew about climate change in the late 1970s but publicly denied the scientific consensus for decades, according to 2015 reporting by InsideClimate News and the Los Angeles Times that spawned the hashtag #ExxonKnew and fueled a wave of climate litigation against the oil major.

The findings by E&E News reveal that GM and Ford were "deeply and actively engaged" since the 1960s in understanding how their cars affected the climate, said Carroll Muffett, president and CEO of the Center for International Environmental Law.

"We also know that certainly by the 1980s and 1990s, the auto industry was involved in efforts to undermine climate science and stop progress to address climate change," Muffett said. "But a different path was available."

Today the companies acknowledge that climate change is a problem and in statements to E&E News outlined their plans to increase production of clean cars.

A Ford spokesman said the company knows climate change is real and is "addressing it right now" by investing more than $11 billion to electrify its bestselling vehicles while aiming to run its manufacturing plants with 100% renewable energy in 15 years.

GM, in a brief response, pointed to steps it's taking to reduce emissions, such as releasing an electric version of its Hummer, which for years has embodied the popularity of gas-guzzling SUVs. The company downplayed its past rejection of climate action.

"There is nothing we can say about events that happened one or two generations ago since they are irrelevant to the company's positions and strategy today," a GM spokesman said.

Ruth Reck and GM

In 1965, a young physicist became one of the first women to join General Motors Research Laboratories in Warren, Mich. Her name was Ruth Annette Gabriel Reck, and she would set the company on a course toward greater scientific understanding of how the greenhouse effect was raising temperatures on Earth.

A Midwesterner, Reck had in 1954 become the youngest person to graduate from Minnesota State University, Mankato, at just 18 years old. After earning a doctorate in physical chemistry from the University of Minnesota, she joined GM with plans to continue studying that subject.

But in her first week on the job, Reck met with Marvin Leonard "Murph" Goldberger, a visiting physicist from Princeton University who later would become president of the California Institute of Technology. Goldberger convinced her to study climate change instead.

"He said, 'You will never regret it. It really is an important topic,'" Reck recalled in one of several phone interviews with E&E News.

Ruth Reck. Minnesota State University

With the approval of her supervisors, Reck began studying global warming in the late '60s. The first topic she explored was aerosols, or tiny particles that can come from automobiles, power plants and factories.

GM executives were optimistic about the research. They believed it would show aerosols had a significant cooling effect on the atmosphere, canceling out the warming effect of carbon dioxide.

The executives thought aerosols "might actually negate the effects of the CO2 coming off. And so they were positively thinking that maybe the use of fossil fuels by the automobile could be neutral," Reck said.

The findings showed otherwise.

"Of course, that didn't happen at all," she said. "First of all, their lifetime is very short, whereas CO2 is very, very long. ... It didn't play out at all the way they wanted it to happen."

The executives nonetheless allowed Reck to publish her findings in several peer-reviewed scientific journals. In a 1975 paper in Science, she asserted that aerosols caused "heating of the atmosphere near the poles."

Reck recalled warning her colleagues that higher temperatures in the Arctic could cause ice sheets to melt, which could trigger sea-level rise and other serious consequences.

"It's all a question of perspective, whether you think ... melting all the ice in the northern regions is bad or not," she said. "And I said, 'Because it disturbs the entire globe and it disturbs what food we can grow and everything else and the whole balance of the entire Earth atmosphere system, yes, I think it is bad.'"

Syukuro "Suki" Manabe. Bengt Nyman/Wikipedia

In the late '60s and early '70s, Reck also collaborated with two prominent scientists at Princeton's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory named Richard "Dick" Wetherald and Syukuro "Suki" Manabe, who had created one of the first one-dimensional models of the Earth's atmosphere.

In a 1974 paper in the Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, Wetherald and Manabe found that in response to a doubling of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the temperature increased at the Earth's surface and in the troposphere, while it decreased in the stratosphere.

The pair allowed Reck to borrow their model and run simulations on the IBM computers at GM Research Labs. At the time, the computers were a relatively new invention, and they were the size of large refrigerators.

Wetherald died in 2011 after more than 44 years at the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, which later became part of NOAA, according to an obituary that noted his work "in the field of greenhouse warming."

In an interview, Manabe — now 89 years old and retired — recalled working with Reck on the cutting-edge research.

"I was one of the first people who started developing climate models," Manabe said, adding, "I'm sure that General Motors' research group was very interested in climate change research, mainly because they produced the car, which emitted a large amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere."

CONTINUE TO READ MORE ON THE ORIGINAL SOURCE