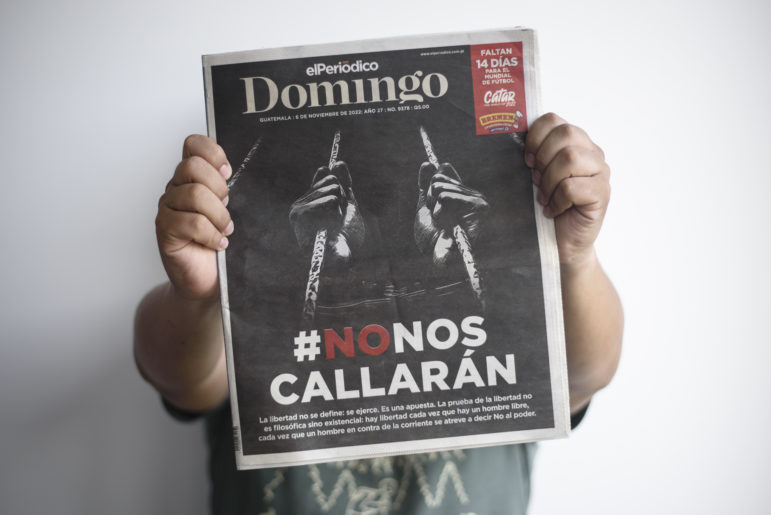

Ramón Zamora, son of detained journalist José Rubén Zamora, holds one of the last printed editions of elPeriódico. The cover reads “We won’t be silenced.” Image: Courtesy of Raúl F. Pérez Lira

When the award-winning Guatemalan journalist José Rubén Zamora was detained at his home in July last year, local and international organizations called for his immediate release, citing press freedom concerns.

But Rafael Curruchiche, the controversial head of the Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Impunity (FECI), addressed the public to say Zamora was being detained as a businessman, not as a journalist. An official insisted the case was “not about political persecution.”

Zamora is the founder and former president of elPeriódico, a print and digital publication known for its critical voice and for its investigations focused on government corruption. Since it was founded in 1996, its founder and staff have been the targets of assassination attempts, kidnappings, raids, and threats.

“The case of José Rubén is paradigmatic… He’s the director of the most important critical outlet in Guatemala and suddenly he’s in jail.” — Journalist Melissa RabanalesThe campaign against elPeriodico is part of a broader assault against independent media around the world. But while journalists in Europe and North America have seen a jump in harassment lawsuits and attacks on the press, what is happening in Latin America is of a different magnitude. The attacks are particularly vicious in Guatemala, a Central American country with a population of 18 million and a volatile past.

More recently, elPeriódico has faced an advertiser boycott, while a number of criminal investigations have been launched against Zamora and the staff of the newspaper, maneuvers widely seen as politically motivated attempts to hinder critical reporting.

“I believe the state has a new repertoire to silence people,” says Ramón Zamora, an anthropologist and one of José Rubén’s sons. “They found very useful and efficient tools in the law.”

José Rubén Zamora, founder of elPeriodico, faces numerous criminal charges that threaten the future of his newspaper. Image: Screenshot, elPeriodico

The main charge against Zamora — a previous winner of the International Press Institute’s World Press Freedom Hero Award and the International Press Freedom Award of the Committee to Protect Journalists — is related to a financial payment he says he received on behalf of the newspaper.

Prosecutors accuse Zamora of blackmail, influence peddling, and laundering roughly US$38,000. Zamora’s defense denies these claims, saying that the money was obtained legally and was intended to finance elPeriódico, which had been losing advertising clients due to government threats. (The defense’s arguments have, so far, been rejected in court.)

But even as this case rumbles on – Zamora is currently awaiting his next hearing — two of his former lawyers were arrested in relation to a second alleged money laundering case.

The timing of the legal assaults against Zamora and those close to him has also raised concerns. The country has a general election this year, which Human Rights Watch has called “crucial for Guatemala’s fragile democracy.”

The high-profile arrest of Zamora ahead of those elections, warns Arlene Getz of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), “sends a chilling message to journalists, especially investigative and independent reporters… amid an ongoing crackdown on prosecutors, judges, and journalists who previously brought corruption cases to light.”

Symptom of a Broader Press Freedom Crisis

A supporter carries a banner that reads, in Spanish, “We are all Jose Ruben Zamora.” Image: Courtesy of Oliver de Ros and the “NoNosCallarán” collective

Across Latin America, journalists are facing a series of threats and challenges. Central American journalists are fleeing their homes in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua to set up newsrooms abroad in the face of safety and security issues. Meanwhile, international organizations are raising the alarm about a deteriorating press freedom outlook: 30 journalists were killed in Latin America in 2022, according to the CPJ, accounting for nearly half of the 67 journalists and media workers killed worldwide.

In Guatemala, the case of Zamora takes place in an environment where journalists, activists, opposition leaders, judges, and prosecutors who are considered problematic by the government are being criminalized.

“Laws are being used to silence the media,” says Hazel Feigenblatt, program manager for Latin America and the Caribbean at the Institute for War and Peace Reporting. “In the case of Guatemala, we’ve seen both threats and fulfilled threats of legal cases against journalists for causes that appear to be politicized.”

In the Reporters Without Borders’ 2022 Press Freedom Index, Guatemala fell to 124th out of 180 countries, a drop of eight places from its 2021 ranking — and nearly 50 places lower than its position 12 years ago, when it was ranked 77th in the world. The group’s researcher noted that “journalists and media outlets who investigate or criticize acts of corruption and human rights violations frequently suffer aggression in the form of harassment campaigns and criminal prosecution.”

The Association of Journalists of Guatemala (APG) has counted nearly 400 cases of harassment and restrictions on journalists during the course of current President Alejandro Giammattei’s tenure, including the use of law to censor, criminalize, and obstruct the work of reporters. The organization claims that Attorney General Consuelo Porras “makes up cases and persecutes journalists.” Complaints by journalists, meanwhile, fare badly. Last year, the Public Ministry shelved 34 complaints (meaning they were accepted, but not investigated more thoroughly) filed by reporters and media workers; 81 others were dismissed.

Besides the money laundering case that keeps Zamora in prison, there are at least 17 open cases against him and other journalists from elPeriódico — including a number being brought under a femicide law originally meant to protect victims of domestic violence.

Guatemala has tumbled down the Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index, ranking nearly 50 places lower than its position 12 years ago.In 2022, a court blocked Zamora and two other journalists from elPeriódico from publishing stories about alleged irregularities in the contract of Dina Alejandra Bosch Ochoa, a controversial employee of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal. Granting Bosch’s petition, the judge extended the restriction to any coverage of her direct family, including a prominent magistrate of Guatemala’s Constitutional Court.

“They are using a law created to protect vulnerable people, in this case, women that live in violent situations, to protect people with a lot of power within the state,” says Ramón Zamora.

The same tactic was used by previous administrations. Back in 2013, former Vice President Roxana Baldetti — who was later jailed for corruption — argued that an article by Zamora examining her lavish lifestyle and questioning her connections was misogynistic. Baldetti got a restraining order imposed on Zamora, and while a judge lifted the measure months later, public servants still apply the same strategy: Investigative journalists like Marvin del Cid and Sonny Figueroa, among others, have had similar experiences.

Dual Threat to Accountability

While on the one hand there are concerns the judicial system is being weaponized against journalists, on the other, there are signs the legal system has itself come under attack. There are at least 30 public officers, judges, and prosecutors in exile.

Reporter Melisa Rabanales decided to dig into the case of Virginia Laparra, the district prosecutor in Quetzaltenango for the prosecuting agency FECI. Laparra had been arrested and put into pre-trial detention after accusations of abuse of power.

“Laws are being used to silence the media.” — Hazel Feigenblatt, Institute for War and Peace Reporting“It was an important case because the criminalization [of political opponents] in Guatemala was moving forward in giant steps,” says Rabanales in an interview. “We knew about the prosecutors in exile, about the judges, but this was the first prosecutor from the FECI being criminalized.”

Rabanales and the podcast team from Agencia Ocote, a multi-platform nonprofit that works at the cross-section of investigative and narrative journalism, got into Mariscal Zavala prison, where Laparra was being held. Although security personnel saw the audio recorder and approved it, a criminal complaint was later filed against the team, arguing it was illegal to take a recording device into a prison.

Anonymous Twitter troll factories, known as “netcenters” in Guatemala, published details from the case and posted personal information about Rabanales, a practice increasingly being used to intimidate journalists in that country. Seeing what had happened to Zamora and fearing she could be in danger, she left the country.

“The case of José Rubén [Zamora] is paradigmatic… He’s the director of the most important critical outlet in Guatemala and suddenly he’s in jail,” explains Rabanales. “This has escalated and it’s a difficult situation for independent media because you don’t have the support that everyone else has. And, if you’re a woman, if you’re Indigenous, or if you live in a community, it’s way worse.”

Rabanales mentions the case of Carlos Choc, a Maya Q’eqchi’ journalist, who was denounced for “incitement to commit crimes” by members of the national police after covering a protest against a mine in his region. Choc and other members of Prensa Comunitaria, a community-based news outlet, have investigated and published reports on alleged irregularities in mining operations in their territories.

But while the work of reporters at places like Agencia Ocote was being shut down in Guatemala, it was being celebrated abroad: last year the team received the prestigious Gabo Award for its podcast “It Wasn’t the Fire” (No fue el fuego), an investigation into impunity and a fire that took the lives of 41 girls in a shelter.

For Rabanales, the award served as a reminder of the importance of their investigative journalism. “Work has results and we must continue speaking out,” she says. Even if in her case, that is from overseas.

Though elPeriódico suspended its print edition in December, Zamora has said he will keep fighting to clear his name. The case against him, he stresses, is “politically motivated,” but he’s promised he will “continue with the struggle and affirm no crime was committed.”

Additional Resources

Under Attack: El Faro’s Gutsy Reporting in Latin America

Editor’s Pick: 2022’s Best Investigative Stories from Latin America

10 Tips for Founding a Successful Investigative Startup

Raúl F. Pérez Lira is a photographer and writer reporting on topics related to human rights violations and environmental struggles in northern Mexico. He is currently part of Raichali, an independent journalism project based in Chihuahua that is part of the Periodistas de a Pie media alliance.

Raúl F. Pérez Lira is a photographer and writer reporting on topics related to human rights violations and environmental struggles in northern Mexico. He is currently part of Raichali, an independent journalism project based in Chihuahua that is part of the Periodistas de a Pie media alliance.

The post In a Hostile Climate, Guatemala’s Journalists Fear the Law Being Turned Against Them appeared first on Global Investigative Journalism Network.

1 year ago

71

1 year ago

71