For many, the forest is more than just a lush, green backyard to camp, hike, or just get away from the banal of life. In West Papua, the forests are their paradise, their home, and especially, their identity. It’s something that the Papuan peoples have been fighting to protect for decades, as infrastructure development and industrial plantations threaten to take over their paradise. That’s why I needed to meet the community leaders and young people who are working together to save the Papuan forest.

A Cendrawasih (bird of paradise) on a tree in Malagufuk village, located in the rainforest in Kalasou valley, Sorong, West Papua. © Jurnasyanto Sukarno / Greenpeace

A Cendrawasih (bird of paradise) on a tree in Malagufuk village, located in the rainforest in Kalasou valley, Sorong, West Papua. © Jurnasyanto Sukarno / GreenpeaceAfter a long journey, through winding roads, crossing streams, thickly forested areas, mountains and valleys, my colleagues and I reached Berap village in Nimbrongkrang District in West Papua, close to the capital Jayapura. We were greeted with curious children who were jumping off a small wooden footbridge over the deep-blue river. We were soon offered some beverages and were comfortably sitting in a para para – a traditional community room. As we sat feeling refreshed and settled after our journey, the head of Iram Takay (an Indigenous institution) of the Tecuari clan of the Namblong tribe, Mr. Abner Tecuari, presented to us a neatly rolled card paper. As he unrolled it we saw a hand drawn map: this was the community’s visualization of the land, forest, plantations, hamlets, rivers, and surroundings. With more than 42 clans in this tribe they were trying to map clan boundaries to find ways to prevent a permit that would give a private investor the right to cut the intact forest for palm oil plantation.

A Papuan boy, jumps in to the Blue River (Kali Biru) that is located in Knasaimos landscape in Teminabuan, South Sorong, West Papua. © Jurnasyanto Sukarno / Greenpeace

A Papuan boy, jumps in to the Blue River (Kali Biru) that is located in Knasaimos landscape in Teminabuan, South Sorong, West Papua. © Jurnasyanto Sukarno / GreenpeaceThe quest for justice…

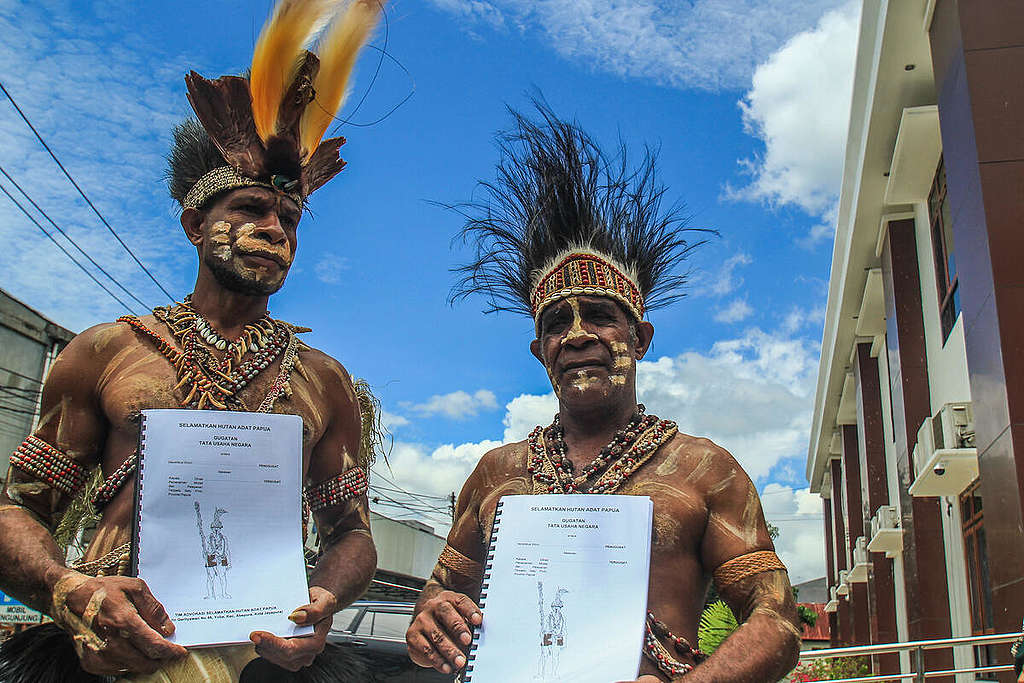

As is the case in many similar situations, decisions that have serious impacts on the lives of Indigenous peoples are often taken in towns, cities, or capitals far away from where they live. Back in Jayapura town, an Indigenous leader, Hendrikus’ Franky’ Woro filed a lawsuit at the Jayapura State Administrative Court challenging the plan by a Malaysian-owned palm oil company to clear tens of thousands of hectares of West Papuan forest. The lawsuit calls for the revocation of a permit issued by the Papua provincial government covering traditional Indigenous land of which Franky Woro is a joint owner, and was filed on behalf of the clan. This is the first forest and land use case brought by an Indigenous peoples in Indonesia. The filing not only represented an administrative act, but a cultural resistance in action, holding the state to account.

Papuan indigenous environmentalist from the Awyu Tribe Hendrikus ‘Franky’ Woro (leftt) and Kasimilus Awe (right), file an environmental and climate change lawsuit at the Jayapura State Administrative Court (PTUN). This lawsuit concerns an environmental permit issued by the Investment and One Stop Service Office of Papua Province for the palm oil company PT Indo Asiana Lestari (PT IAL). © Gusti Tanati / Greenpeace

Papuan indigenous environmentalist from the Awyu Tribe Hendrikus ‘Franky’ Woro (leftt) and Kasimilus Awe (right), file an environmental and climate change lawsuit at the Jayapura State Administrative Court (PTUN). This lawsuit concerns an environmental permit issued by the Investment and One Stop Service Office of Papua Province for the palm oil company PT Indo Asiana Lestari (PT IAL). © Gusti Tanati / GreenpeaceLater in the week, I attend a Papuan cultural festival in downtown Jakarta city. Around me were several young people, attentively listening to speakers in panel discussions, asking questions, learning some Papuan painting, and arts and crafts. The discussions focused on issues like the role of women in forest conservation, violence unleashed by the state in many different forms, issues of identity and race and the active loss of staple food, sago, due to the incentivisation of rice (used part of assimilation with other islands, thereby resulting in artificial dependencies on food not grown locally). These young folks, the leaders of today and tomorrow, seemed to relish the opportunity to better understand and appreciate the rich diversity of Papua (rather distant to the rest of Indonesia) and the social, political, and cultural challenges facing this island, its identity, and its peoples. As the formal session ended, came the beats of music, song, and dance depicting the richness of the Papuan culture. I could not hold myself back and danced to the beats.

The crowd dances as the Papuan reggae group Labadios performs during Ranipa Festival in Jakarta © Jurnasyanto Sukarno / Greenpeace

The crowd dances as the Papuan reggae group Labadios performs during Ranipa Festival in Jakarta © Jurnasyanto Sukarno / GreenpeaceI am.. because you are

The challenges faced in West Papua are very similar to those faced by many Indigenous people and local communities right across the world. Indigenous lands, many of which are of sacred and cultural importance, are being degraded and destroyed in the name of ‘economic development’. They feed the unsatiating greed of the current capitalist system, which manipulates each one of us to over consume and live an unsustainable lifestyle. It also feeds the greed of the top 10% super rich who are responsible for 50% of greenhouse gas emissions.

Good intact forests that have survived for millions of years are being cleared for commodities like palm oil, timber, pulp, beef, and mining for minerals. Nature is seen as just another commodity that can be bought and sold. These forests, and the millions of species which depend on them, once lost, are lost forever. And make no mistake, whilst planting trees, at the right time at the right place can be good, this is not the real solution. What we urgently need is to end all deforestation and to stop clearing land to grow crops for industrial farming for meat and biofuels.

Residents from Mangroholo and Sira village of Sorong, West Papua learn to process sago flour from a villager from Sungai Tohor during a training in Sungai Tohor, Meranti islands, Riau. Sago is a starch extracted from the pith of various tropical palm stems. © Fully Syafi / Greenpeace

Residents from Mangroholo and Sira village of Sorong, West Papua learn to process sago flour from a villager from Sungai Tohor during a training in Sungai Tohor, Meranti islands, Riau. Sago is a starch extracted from the pith of various tropical palm stems. © Fully Syafi / GreenpeaceSaving intact forests and restoring degraded ones needs to be the top most priority for those who are keen to address the biodiversity crisis. Many corporations who continue to rely on commodities that destroy good intact forests, indulge in monoculture tree plantations to compensate for this irreplaceable loss. But such actions are big lies as monocultures destroy biodiversity and local livelihoods yet they continue with the patronage of the state and our political leaders.

What we need is a deeper appreciation of using culture in our struggles for a better planet. What I saw and experienced in Indonesia is how cultural campaigning can be a powerful tool to enhance people’s power to address serious and urgent issues, including loss of forests, and resist state policies that destroy culture and heritage. Many older Papuans have a deep and intimate relationship with the forests, which connects them to their ancestors, spirits, and nature and are passed down through oral traditions. Efforts have to be made to transmit these ancient wisdoms on protecting and restoring nature to younger generations. Starting with the state via the education system, social media influencers, schools, faith-based institutions, and NGOs have to play their part in doing so, especially in the digital world.

Aerial view of primary forest near the river Digul in southern Papua. © Ulet Ifansasti / Greenpeace

Aerial view of primary forest near the river Digul in southern Papua. © Ulet Ifansasti / GreenpeaceOn World Forest Day, continuing to push for systemic change, challenging the current status quo by holding governments and corporations to account is a must. We can also use this day to reconnect and deepen our relationship with nature. The shift we need in our communities, societies and states is to build this deep connection linked to aspects of culture, traditions and spirituality. Once you hope, everything is possible.

Savio Carvalho is a global campaign lead at Greenpeace International, working to protect and promote people’s rights to a sustainable and healthy environment. Follow him on Twitter @savioconnects

1 year ago

77

1 year ago

77