Shutterstock

ShutterstockIf you take a plunge in the sea this winter, you might notice it’s warmer than you expect. And if you’re fishing off Sydney and catch a tropical coral trout, you might wonder what’s going on.

The reason is simple: hotter water. The ocean has absorbed the vast majority of the extra heat trapped by carbon dioxide and other greenhouses gases. It’s no wonder heat in the oceans is building up rapidly – and this year is off the charts.

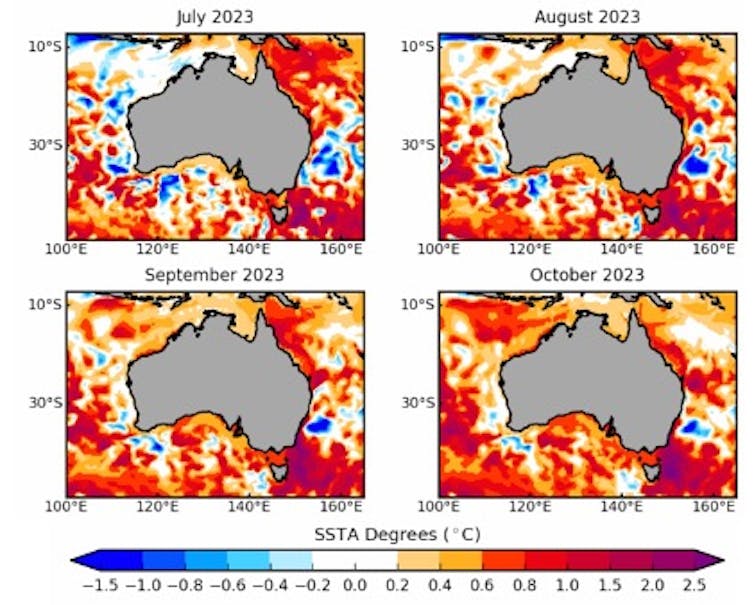

That’s even without the likely arrival of El Niño, where the Pacific Ocean gets warmer than usual and affects weather all over the world. Our coastal waters are forecast to be especially warm over the coming months, up to 2.5℃ warmer than usual in many places.

Oceans around Australia are forecast to be much warmer than usual. SSTA stands for projected Sea Surface Temperature Anomaly, the difference between forecast ocean temperatures and a historical baseline period encompassing 1990–2012.

Bureau of Meteorology

Oceans around Australia are forecast to be much warmer than usual. SSTA stands for projected Sea Surface Temperature Anomaly, the difference between forecast ocean temperatures and a historical baseline period encompassing 1990–2012.

Bureau of Meteorology

Many marine species live within a narrow temperature range. If the water heats up, they have to move, and if they don’t, they might die. So those that can move, are moving. In Australia, at least 200 marine species have shifted distributions since 2003, with 87% heading south.

This pattern is happening all around the world, both on land and in the ocean. This year, the warmer ocean temperatures during winter mean Australia’s seascapes are likely to be more like summer. So, the next time you go fishing or diving or beachcombing, keep your eyes peeled and your camera ready. You may glimpse the enormous disruption happening underwater for yourself.

Here are eight species on the move

1. Moorish idol (Zanclus cornutus)

Historic range: northern Australia

Now: This striking fish can now be seen south of Geraldton in Western Australia and Eden in New South Wales.

This is a great fish for divers to spot on hard-bottomed habitats.

Moorish Idols are heading south to escape the heat.

Shutterstock

Moorish Idols are heading south to escape the heat.

Shutterstock

2. Branching coral (Pocillopora aliciae)

Historic range: northern NSW

Now: Look out for this pale pink beauty south of Port Stephens, not far from Sydney.

Seemingly immovable species like coral are fleeing the heat too. They’re already providing habitat for a range of other shifting species like tropical fish and crab species.

3. Eastern rock lobster (Sagmariasus verreauxi)

Historic range: common in NSW

Now: South, as far as it can get. It’s now found in Tasmania and even in South Australia.

This tasty greenish crustacean doesn’t like heat and has moved south into the territory of red southern rock lobsters (Jasus edwardsii).

4. Gloomy octopus (Octopus tetricus)

Previous range: common in NSW

Now: As far south as Tasmania.

Look out for this slippery, smart invertebrate in Tasmanian waters this winter. You might even spot the octopus nestled down with some eggs, as this looks to be a permanent sea change.

The gloomy octopus is also known as the common Sydney octopus.

Niki Hubbard, Wikimedia, CC BY

The gloomy octopus is also known as the common Sydney octopus.

Niki Hubbard, Wikimedia, CC BY

5. Whitetip reef shark (Triaenodon obesus)

Previous range: northern Australia

Now: South of K'gari (formerly known as Fraser Island).

Classed as vulnerable in parts of the world, this tropical shark is a slow swimmer and never sleeps. It poses very little danger to humans.

6. Dugongs (Dugong dugon) Previous range: northern Australia

Now: As far south as Shark Bay in WA and Tweed River in New South Wales.

Our waters are home to the largest number of dugong in the world. But as waters warm, they’re heading south. That means more of us may see these elusive sea-cows as they graze on seagrass meadows.

Some of the most adventurous have gone way out of their normal range – in 2014, a kitesurfer reported passing a dugong at City Beach, Perth. As a WA wildlife expert says, dugongs may occasionally stray further south of Shark Bay but “given the recent warming trend […] more dugong sightings might be expected in the future”

7. Red emperor (Lutjanus sebae) and other warm water game fish

Previous range: northern Australia

Now: Appearing much further south – especially in WA.

Look for red, threadfin, and redthroat emperors in southwest WA as the Leeuwin current carries these warm water species south. As WA fisheries expert Gary Jackson has said, this current is a warming hotspot, acting like a warm water highway for certain marine species.

These fish are highly sought after by fishers.

8. Long-spined sea urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersii)

Historic range: NSW and Victoria

Now: Tasmania

Look out for these spiky critters in southern and western Tasmania. The larvae of these urchins have crossed the Bass Strait and found a new home, due to warming waters. Urchins are grazers and can scrape rocks clean, creating urchin barrens where nothing grows. That’s bad news for kelp forests and the species which depend on them. In response, Tasmanian authorities are working to create a viable urchin fishery to keep numbers down.

Long-spiked sea urchins are voracious eaters of seaweed.

John Turnbull/Flickr, CC BY

Long-spiked sea urchins are voracious eaters of seaweed.

John Turnbull/Flickr, CC BY

Read more: Sea urchins have invaded Tasmania and Victoria, but we can’t work out what to do with them

You can help keep watch

For years, fishers, snorkellers, spearfishers and the general public have contributed their unusual marine sightings to Redmap, the Australian citizen science project aimed at mapping range extensions of species.

If you spot a creature that wouldn’t normally live in the waters near you, you can upload a photo to log your sighting.

For example, avid spearfisher Derrick Cruz logged a startling discovery with Redmap in 2015: A coral trout in Sydney’s waters. As he told us: “I’ve seen plenty of coral trout in tropical waters, where they’re at home within the coral. But it was surreal to see one swimming through a kelp forest in the local waters off Sydney, much further south than I’ve ever seen that species before!”

How does tracking these movements help scientists? Many hands make light work. These vital observations from citizen scientists have helped researchers gain deeper understanding of what climate change is doing to the natural world in many places, from bird migrations to flowering plants to marine creatures.

So, please keep an eye out this year. The heat is on in our oceans, and that can mean sudden change.

Read more: Sydney's waters could be tropical in decades, here's the bad news...

Gretta Pecl receives funding from the Australian Research Council, CSIRO, FRDC, DCCEEW, Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment, and Department of Primary Industries NSW.

Curtis Champion receives funding from the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation. He works for NSW Department of Primary Industries.

Zoe Doubleday receives funding from the Australian Research Council, Australian Academy of Science, and Fisheries Research and Development Corporation.

1 year ago

94

1 year ago

94