One of the most significant achievements of the 26th United Nations climate conference in Glasgow (COP26) three years ago was the launch of the Global Methane Pledge. The goal is to reduce global methane emissions at least 30% by 2030.

Methane (CH₄) is the second most significant climate pollutant after carbon dioxide (CO₂). In the words of one of the architects of the pledge, then US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, John Kerry, “tackling methane is the fastest, most effective way to reduce near-term warming and keep 1.5°C within reach”.

Australia signed up to the methane pledge in October 2022. It was a good start, but a promise is not a plan. To date, Australia has no official methane reduction targets, nor an agreed strategy to deal with this dangerous pollutant.

The Climate Council’s report, released today, sets out actions Australia can take right now to cut methane emissions. We need to get on with it.

Why should we care about methane?

Methane in the atmosphere is rising at a record rate: up about 260% since preindustrial times to a high not seen for at least 800,000 years.

Research just released shows if we don’t act, the problem will only worsen. It suggests increases in atmospheric methane are outpacing projected growth rates – threatening the global goal of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050.

The gas is likely responsible for at least 25 to 30% of warming Earth has experienced since the Industrial Revolution.

Methane is a “live fast, die young” gas, persisting in the atmosphere for a relatively short amount of time. But while it’s there, it punches above its weight in warming. Over 20 years, methane is about 85 times more effective at trapping heat than the equivalent amount of carbon dioxide.

After 100 years, it’s still about 28 times more effective at trapping heat.

This means methane has an outsized impact on warming in the short term, turbocharging unnatural disasters such as floods, bushfires and heatwaves.

Where does methane come from?

Roughly half of global methane pollution comes from human activities. The rest comes from natural sources such as wetlands and soils.

Australia produces more than its fair share of methane because we have such large fossil fuel and agriculture industries. We are the world’s 12th largest methane polluter, producing four to five times as much methane as would be expected based on population alone.

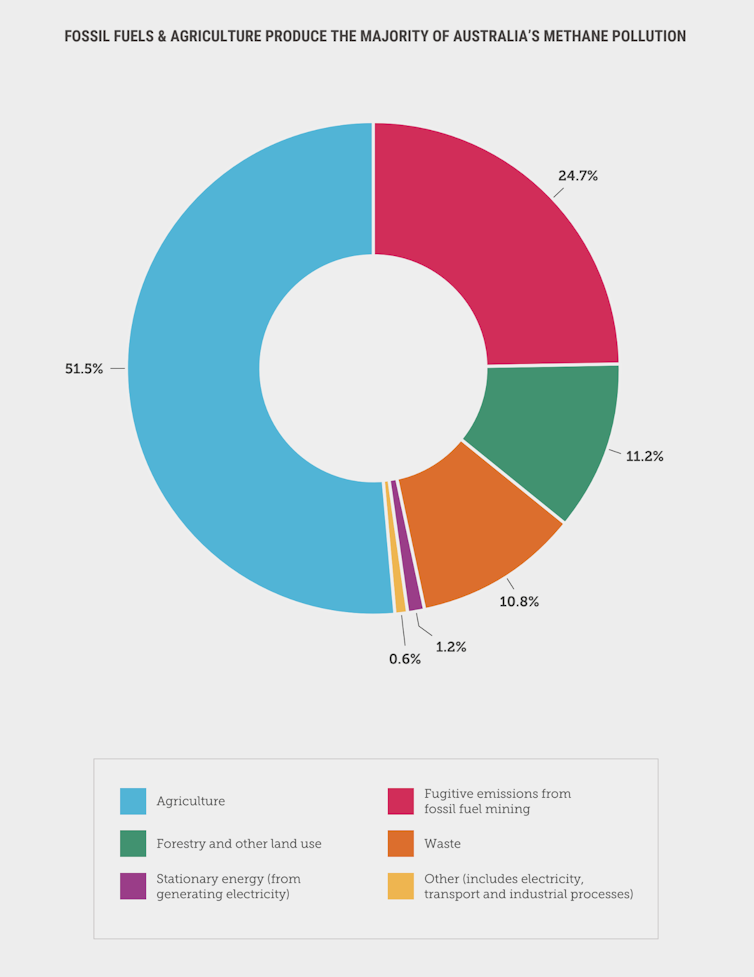

In the year to December 2023, Australia produced nearly four million tonnes of methane. The main sources from human activity were agriculture (52%), fossil fuel mining (25%) and waste (11%). The good news is there are plenty of ways to reduce emissions in each sector that we can and should implement right now.

Agriculture and fossil fuels produce most of Australia’s methane pollution.

The Climate Council, using data from the National Greenhouse Gas Inventory Quarterly Update: December 2023 (DCCEEW, 2024).

Agriculture and fossil fuels produce most of Australia’s methane pollution.

The Climate Council, using data from the National Greenhouse Gas Inventory Quarterly Update: December 2023 (DCCEEW, 2024).

What can we do about it?

The largest source of methane emissions in agriculture is the burps of ruminant animals – mainly cows and sheep.

Promising research suggests each animal’s methane production can be cut by as much as 90% using daily feed supplements. These include supplements from the red seaweed Asparagopsis, and the chemical marketed as 3-NOP.

Other approaches to reducing methane emissions from animals also show promise. They include vaccines that target methane-producing microbes in their guts, methane-reducing pasture species, and selective breeding.

These solutions should be scaled up and farmers encouraged to use them – for instance, by being eligible for carbon credits under the Emissions Reduction Fund.

Providing consumers with point-of-sale information about the climate impacts of their food choices could also serve to reduce the nation’s methane emissions. And the market can be encouraged to develop clear regulatory pathways for securing approval of animal-free protein and other lower-impact foods.

More than 90% of our food waste ends up in landfill where it produces methane when it rots. Composting is much better for the environment. Investing in organic collection services for food and garden waste, and tightening regulations to capture gas at landfill sites, can address much methane pollution from the waste sector.

We can’t control what we don’t measure. Currently, methane emissions are largely reported to the Clean Energy Regulator using indirect and outdated methods. The International Energy Agency estimates Australia could be under-reporting methane emissions from the coal and gas sector by up to 60%.

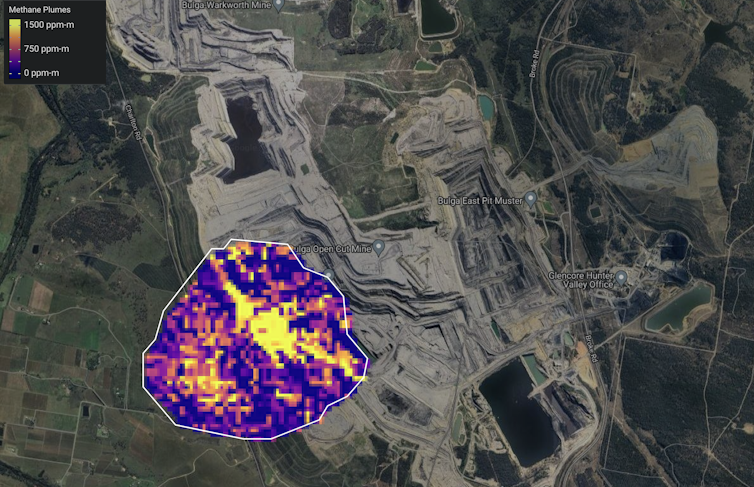

Fortunately, new global satellite capacity and, in Australia, the Open Methane visualisation tool, mean we can measure methane at its source far more accurately than before.

Methane emissions observed by satellite near Glencore’s Hunter Valley Coal Mine in January 2023.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Methane emissions observed by satellite near Glencore’s Hunter Valley Coal Mine in January 2023.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

The federal government should make all coal and gas corporations directly measure and report their methane emissions from existing mines, in line with international best practice.

Every coal mine and gas plant produces methane during mining and processing. While we work towards phasing out fossil fuel mining, a few practical actions can reduce methane pollution:

- require underground coal mines to capture and destroy the methane vented into the atmosphere

- ban all non-emergency flaring and venting of gas

- require all gas mining companies to address leaky infrastructure

- ensure mining companies seal inactive mines.

Time for action

Without concerted action, global methane pollution from human activities is expected to rise 15% this decade. On the other hand, meeting the commitments of the Global Methane Pledge can reduce warming in the next few decades.

If the goals of the pledge are met, we could shave about 0.25°C off the global average temperature by mid-century, and more than 0.5°C by 2100.

The federal government should establish a national methane reduction target and a dedicated action plan. This should be part of our updated national emissions reduction target, due to be set in 2025.

We can’t take our foot off the pedal in cutting carbon dioxide. But at the same time, in the words of United Nations head Antonio Guterres, we have to do “everything, everywhere, all at once”.

Lesley Hughes is a Director and Councillor with the Climate Council of Australia. She has previously received funding from the Australian Research Council. She is a member of the Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists, a Director of the Environmental Defenders Office and a member of the Climate Change Authority

3 months ago

41

3 months ago

41