Journalists are bracing for the outcome of the 2024 U.S. presidential election. CPJ’s research ahead of the November vote finds that the hostile media climate fostered during Donald Trump’s presidency has continued to fester, with members of the press confronting challenges – including violence, lawsuits, online harassment, and police attacks – that could shape the global media environment for decades. A special report by Katherine Jacobsen.

Introduction

In the moments after a would-be assassin’s bullet grazed the ear of presidential candidate Donald Trump, supporters at the July campaign rally where he was injured were quick to seek scapegoats.

“Fake news! This is your fault,” was one accusation noted by Axios reporter Sophia Cai. Cai, who witnessed the assassination attempt from the rally’s media cordon, also reported an ominous warning lobbed at the press section: “You’re next! Your time is coming.”

The threats to the media that day stopped short of the physical assaults endured by several reporters on January 6, 2021, when thousands of Trump supporters attacked the U.S. Capitol in a failed attempt to block the certification of Joe Biden’s election win and keep Trump in the White House.

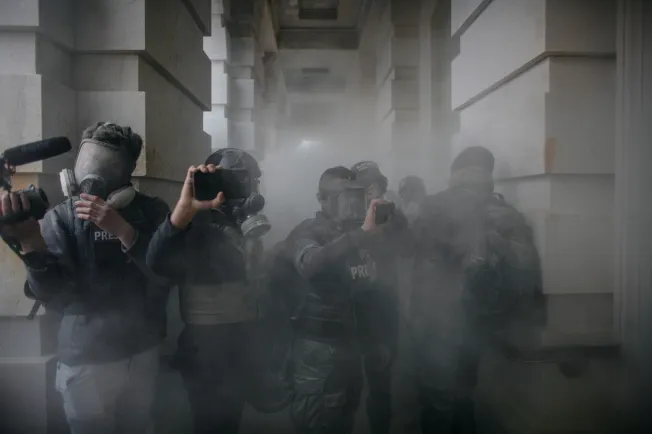

Journalists report from the U.S. Capitol as pro-Trump protesters storm the building on January 6, 2021, to contest the certification of the 2020 presidential election. Some journalists say they are still wrestling with the trauma of covering the riot.

(Photo: Reuters/Ahmed Gaber)

But both events were evidence of the high stakes for press freedom in the 2024 U.S. presidential election – both inside the nation seen as a global standard-bearer for free expression and in countries beyond its borders.

In the years since the Trump administration’s angry attacks on the media and the January 6 insurrection, President Biden’s statements on press freedom have restored some sense of normalcy in the relationship between media and the White House. While some journalists have criticized the reduction in access to his vice president, Kamala Harris, since she became the Democratic Party’s nominee for president, her past interactions with the media, including those dating back to her time as a district attorney and state attorney general in California, suggest she likely would continue that more civil relationship.

Security and police officers restrain a man who jumped onto the media area at a Pennsylvania rally for Donald Trump on August 30, 2024. Trump referred to the press during the rally as ‘the enemy of the people.’ (Screenshot: CPJ/WJAC-NBC-TV)

Security and police officers restrain a man who jumped onto the media area at a Pennsylvania rally for Donald Trump on August 30, 2024. Trump referred to the press during the rally as ‘the enemy of the people.’ (Screenshot: CPJ/WJAC-NBC-TV)But friendlier rhetoric from the top levels of the Democratic administration has done little to eliminate the vitriol against the Fourth Estate that blossomed during the Trump years – and that Trump continues to spread during the current campaign season.

Trump’s presidency has been widely seen as bad for press freedom. A 2020 CPJ report found that his administration escalated prosecution of news sources, interfered in the business of media owners, harassed journalists crossing U.S. borders, and used the Espionage Act – a law that has raised grave concerns about its potential to restrict reporting on national security issues – to indict WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. At the same time, Trump undermined the credibility of news outlets by lashing out at reporters, often on the president’s social media feeds, as “corrupt,” “dishonest,” and “enemies of the people.”

On the 2024 campaign trail, Trump has threatened to further his anti-press agenda by strengthening libel laws; weakening First Amendment protections; prosecuting reporters for critical coverage; and investigating the parent company of NBC and MSNBC for the channels’ “vicious” news coverage. He has also called for National Public Radio (NPR) to be defunded. “They are a liberal disinformation machine,” he wrote of the public broadcasting organization on his Truth Social platform in an all-cap post. “Not one dollar!!!”

The denigration of U.S. media, coming at a time when shrinking newsroom budgets, the shuttering of local news publications, and record public mistrust of mainstream outlets have hampered their ability to counter the anti-press narrative, has continued to resonate in the years since Trump lost the 2020 election, helping to fuel extremist and fringe ideas on both the left and the right. The result is an increasingly precarious safety environment for reporters.

CPJ’s interviews with journalists, lawyers, and press freedom advocates over several months ahead of the November vote found that media workers are confronting challenges that include an increased risk of violence, arrest, on- and offline harassment, legal battles, and criminalization. Political polarization, the legacy of the January 6 assault on the Capitol, and a lack of police accountability for their treatment of journalists emerged as additional causes for concern.

Reporters told CPJ that antagonism toward the media leaves them feeling less safe working in their home environments. Some say they feel as though they are operating in a different reality from their readers; that the “alternative facts” of the Trump years have spun entirely different narratives about current events, including the upcoming election.

Overseas, journalists fear that a second Trump term would again embolden foreign leaders to restrict their own media, negatively affecting the global press freedom landscape and undermining those in regions that rely on U.S. aid and support.

‘January 6th was a warning shot’

John Minchillo was used to covering civil unrest. As a photojournalist for The Associated Press with over 15 years of experience working in places like Ukraine, Gaza, Egypt, and Lebanon, security was something baked into his reporting plan, along with the understanding that even the most seemingly routine assignment could turn volatile.

And so, when Minchillo headed to the Capitol on January 6, 2021, one camera on his hip and another in hand, he was prepared: helmet on, press credentials readily visible, and a gas mask protecting his face as he waded into the crowd of rioters massing around the building’s perimeter.

In the thick of the crowd several rioters took hold of Minchillo’s backpack, yanking him backwards down a set of stairs. The crowd continued to push and drag him, tossing him over a wall and yelling as he waved his press credentials, until he was able to move away from the situation.

As dramatic as the assault was, it is not what continues to disturb him about that day, Minchillo told CPJ.

“January 6 stands as a monument to the times that we are in, not because of the violence, but because of the unwillingness of individuals far and wide to see with their own eyes and know what it is without asking for someone else to define it for them,” he said. That unwillingness to accept truthful images strikes at the very purpose of journalism, Minchillo said. If people didn’t trust his images, then it denied the importance of his work.

The riot at the Capitol has been repeatedly analyzed for its wide-ranging implications for democracy. Less remarked upon is the attack’s impact on freedom of the press. Members of the media were a prime target on January 6, as anti-press venom stoked by Trump on the campaign trail and in the White House reached a fever pitch.

According to the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker, of which CPJ is a founding member, at least 18 journalists were assaulted and tens of thousands of dollars of reporting equipment was destroyed during the January 6 rioting.

Among the victims was a New York Times photographer who was attacked after rioters learned where she worked. Even staff members for the local affiliate of the conservative Fox network were not immune as protesters harassed and assaulted its team.

According to the Tracker, nine people have been charged with the assaults on Minchillo and other journalists. Another five have been charged solely in relation to equipment damage outside of the Capitol. In at least 15 other cases of journalists being assaulted on January 6, no additional charges have been brought.

But even if there eventually is full justice in these cases, January 6 will remain a symbol of the failure to acknowledge and confront the hatred of the press that has gone unchecked in much of the country, even as the Biden administration has tried to restore an air of normalcy around media freedom.

Prior to Trump’s rise on the national stage, serious political contenders who misspoke about a factual matter or just made a verbal stumble would jump to address the error in some way. However, the former president changed the playbook entirely – and with it degraded the concept of facts, as well as the messengers delivering those facts, including journalists, Jay Rosen, an associate professor at New York University’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute, told CPJ.

That disdain for facts and their messengers can be seen in the historical framing of January 6 by Trump and his associates.

“It’s easier in a lot of ways for January 6 to just become a dispute between partisans, which is obscene,” said Rosen. “We all saw what happened.”

Beyond the broader implications for democracy and press freedom, some journalists who were on the ground that day say they continue to wrestle with trauma that impacts their work covering Congress.

“Generally speaking, I’m pretty good at compartmentalizing,” said Amanda Andrade-Rhoades, a freelance photojournalist who was on assignment at the Capitol for The Washington Post. “But hearing the audio of January 6th while covering the committee meetings, that’s still frankly very difficult for me,” she said, referring to the congressional investigation into the attacks. “There was a moment during the hearings where they played a piece of footage where you can see a very close friend of mine running down the hallway…having to hide for her life.”

“I really do think that January 6th was a warning shot. It was a wakeup call to the fragility of our democracy and trust in institutions – like journalism, like the government – that’s been eroding for a very long time.”

– Photojournalist Amanda Andrade-Rhoades

Protesters threatened to shoot Andrade-Rhoades, who was injured by crowd control munitions. She said that the denial in some quarters of the reality of the attack on the Capitol has made moving on difficult.

“You can wave a photo in front of people’s faces as much as you want, but it doesn’t necessarily work with the people who created conspiracies around January 6, or for those who truly believe it was a peaceful gathering,” she said. “It almost feels like you’re being gaslit – I was there, I photographed it, I know what happened.”

Matt Laslo, a freelance journalist with over 18 years of experience covering Capitol Hill, spent about 90 minutes on the afternoon of January 6 barricaded in the Senate press gallery holding a wrench and wooden door stopper next to a colleague, who was having a panic attack. Capitol police eventually helped those in the gallery to exit safely.

Since then, Laslo said, he’s been unable to file from the Senate press gallery. Instead, he goes home to his nearby apartment and files his report in the company of his dog, which he got shortly after the insurrection.

“January 6 is always in the back of my mind, but I try not to let it consume me,” he told CPJ.

Covering the 2024 election has caused anxiety for these and other reporters who feel like they’re caught in a strange feedback loop, as Trump continues, four years later, to make false claims of 2020 election fraud a talking point at his political rallies.

“I really do think that January 6th was a warning shot,” said Andrade-Rhoades. “It was a wakeup call to the fragility of our democracy and trust in institutions – like journalism, like the government – that’s been eroding for a very long time.”

Fears of retaliatory violence

On September 7, 2022, Las Vegas Review-Journal staffers gathered around a police scanner in the paper’s office, fluorescent lights beaming down, as they waited to hear whether officers had arrested Robert Telles, the man suspected of killing their colleague Jeff German. After a tense wait, they learned that Telles, a local county public administrator on whom German had reported, had indeed been apprehended.

The newsroom breathed a sigh of relief, feeling a collective, if momentary, sense of peace after its members had worked tirelessly to piece together the clues of who could have violently stabbed German to death on his front lawn five days earlier, on September 2. “It’s what Jeff would have wanted us to do. It’s what Jeff would have done for us,” Las Vegas Review-Journal Executive Editor Glenn Cook told CPJ shortly after German was killed.

Former Clark County public administrator Robert Telles, shown here in court on August 26, 2024, was found guilty on August 28, 2024, of murdering Las Vegas Review-Journal investigative journalist Jeff German. (K.M. Cannon/Las Vegas Review-Journal via AP, Pool)

Former Clark County public administrator Robert Telles, shown here in court on August 26, 2024, was found guilty on August 28, 2024, of murdering Las Vegas Review-Journal investigative journalist Jeff German. (K.M. Cannon/Las Vegas Review-Journal via AP, Pool)German’s investigation into a hostile workplace environment in Telles’ office had contributed to the administrator’s recent defeat in his primary bid for reelection.

“It was a point of conversation throughout our newsroom – you know, how a politician at the bottom of the ballot could be accused of killing Jeff after all the really bad people he’s covered over the course of a four-decade career,” Cook said.

The fatal stabbing of German in retaliation for his journalism was a relatively rare event in the U.S., where 14 journalists and one media worker have been killed in connection with their work since 1992. Unlike in many countries, where murderers of journalists go free, in the U.S. journalists’ killers are usually prosecuted in transparent legal proceedings. Telles was found guilty of German’s murder in August 2024; the man who killed five Capital Gazette workers in 2018 was convicted in 2021.

While the killings of journalists in the U.S. are often explained away as actions of rogue individuals – a reader who felt aggrieved at coverage, a former staff member who felt he was wrongfully terminated, or an angry business owner – they create a broader ripple effect of worry and fear. That can be exacerbated in communities of color, where there have been fewer convictions in cases of murdered journalists.

No one has been prosecuted in the case of Zachary “ZackTV” Stoner, a Chicago hip-hop journalist who was killed in 2018, despite Chicago police arresting Stoner’s suspected killers. The killings of five Vietnamese journalists working in the U.S. between 1981 and 1990 remain unprosecuted. And reporting has indicated that the mastermind of the killing of at least three Haitian radio broadcasters in Miami in the early 1990s has never been held accountable.

“This [fear and stress] is what the actors who commit these violent attacks want,” said Bruce Shapiro, the executive director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma at Columbia University. “They may think that they’re seeking to silence a particular journalist or reporting team, but the idea really is to shut down independent reporting in and of itself.”

It is a dynamic familiar to Martin Reynolds, who was a lead editor on the Chauncey Bailey Project, an investigative series that played a key role in solving the 2007 murder of Bailey, editor of the Oakland Post community newspaper in California, in retaliation for his reporting on a local business, Your Muslim Bakery.

While the shooter, a bakery employee, was initially charged in Bailey’s murder, the Chauncey Bailey Project’s reporting exposed the role played by the bakery owner, Yusuf Bey IV, and another employee, Antoine Mackey, in ordering Bailey’s killing. The project’s work also revealed irregularities in the initial police investigation. Bey and Mackey were both convicted in 2011.

Former Oakland Tribune editor Martin Reynolds, pictured here in 2019, led an investigative series that helped solve the 2007 murder of Chauncey Bailey. ‘Violence against journalists working in the United States was such an anomaly at the time,’ said Reynolds. (Photo: AP/Eric Risberg)

Former Oakland Tribune editor Martin Reynolds, pictured here in 2019, led an investigative series that helped solve the 2007 murder of Chauncey Bailey. ‘Violence against journalists working in the United States was such an anomaly at the time,’ said Reynolds. (Photo: AP/Eric Risberg)“I remember leaving my house when we were in the thick of all this reporting and wondering, ‘Are they going to drive by and shoot me?’” said Reynolds, now the co-executive director of the Maynard Institute, a nonprofit promoting diversity in journalism. “Violence against journalists working in the United States was such an anomaly at the time.”

Over the past 10 years, violence against journalists in the U.S. has increased as government officials, chief among them Trump, have referred to reporters as “enemies” and sought to scapegoat them as a means to divert attention from what they perceived as unfavorable coverage. This corrosive political environment – aggravated by the stress of reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic and vilification by hostile protesters at partisan protests – has altered safety considerations for journalists working in the U.S.

All of this is compounded by a disturbing rise in online harassment, raising credible fears that online threats might turn into real-world harm.

A 2022 survey from the non-partisan Pew Research Center found that one-third of all journalists surveyed reported being harassed on social media in the previous 12 months. Threats of personal physical harm were the most common form of harassment, followed by sexual harassment, harassment based on race or ethnicity, and threats of exposing personal information, according to the Pew study.

Research by CPJ, PEN America, and other groups shows that online harassment campaigns are most likely to target women, journalists of color, LGBTQ+ reporters, and journalists who belong to religious or ethnic minorities.

“[I]t’s very clear that folks are targeted not only for their profession of practicing journalism, but for their identity,” Viktorya Vilk, director of digital safety and free expression for PEN America, told CPJ.

Beyond the psychological impact, online harassment has the potential to inspire real-world violence, said Vilk. “If you jail, physically attack, or kill a reporter, you’re probably going to get a lot of blowback,” she said, whereas online harassment is “not a direct call to kill someone or to physically harm someone, but the implication is there – it’s a dog whistle to do harm.”

One example: About a year after German’s murder, another Las Vegas Review-Journal journalist, Sabrina Schnur, was targeted in an online harassment campaign after she wrote a seemingly straightforward article about a retired police chief who died after his bike was struck by a car. The initial report described the hit-and-run as an accident; police later announced that it was a homicide.

The online attacks against Schnur and others at the publication started weeks after publication, set off by a social media post that was amplified by Elon Musk, owner of Twitter, now called X. In less than a day, Musk’s tweet had garnered over 55 million views and 70,500 reposts.

Even after the paper updated the report’s headline, hundreds of messages poured in, many of them death threats and antisemitic comments directed at Schnur, who is Jewish, as well as threatening comments against other Review-Journal staff.

“I’ve never seen more dehumanizing vitriol and hostility directed at journalists at any time in my career,” executive editor Cook wrote in an op-ed about the “firehose of hate.”

Noting that German’s killer had targeted the journalist through social media, Cook observed that everyone at the Review-Journal “has a heightened sensitivity to this kind of anger.”

In 2023, the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker documented 45 assaults on journalists in relation to their reporting. By early September this year, the site had documented 68 such assaults. The majority of these cases occurred when journalists were out reporting, rather than in retaliation for their work after it was published.

Source: US Press Freedom Tracker

Source: US Press Freedom TrackerJournalists working for large national media outlets are more likely to receive safety training and tools, as well as institutional support that can help mitigate work-related risks. On the local level, where resources are generally more limited and where journalists usually live in the smaller communities they cover, they are more vulnerable to retaliation from disgruntled reporting subjects.

The homes of New Hampshire Public Radio journalist Lauren Chooljian, her parents, and the station’s news director, Dan Barrick, were vandalized following the publication of Chooljian’s investigation into allegations of sexual misconduct by a local businessman. One man has been sentenced by a federal court to 27 months in prison and three years of supervised release; three others have been indicted by a federal judge. In Tennessee, the office of the local Williamson Herald newspaper was vandalized when someone glued and stapled flyers containing white supremacist material to the office and nearby utility poles. The flyers, posted during a contentious election season, accused members of the press, as well as local politicians and activists, of being members of antifa, a disparate group of far-left activists opposed to what they perceive as fascist activity.

For U.S. journalists, these incidents have forced a shifting safety paradigm.

“In the newsrooms in which I worked decades ago, a safety plan meant identifying one person in the newsroom who was going to be the fire marshal,” said the Dart Center’s Shapiro. Now, he said, it means safety assessments, contingency plans, and technology evaluations, with the very real expectation that journalists, even at local media, can be called upon to cover civil unrest. “It’s a pressure cooker unlike anything we’ve seen in modern American journalism,” he said.

An onslaught of lawsuits

When Mississippi Today reporter Anna Wolfe won the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for her investigative series on a $77 million state welfare scandal during the term of former state Governor Phil Bryant, she was elated. However, the celebratory mood around the digital nonprofit’s first Pulitzer was short-lived.

Two days after the Pulitzer announcement, Bryant set in motion what became an onslaught of lawsuits that could endanger reporters’ First Amendment rights and ability to protect confidential sources. First, Bryant sent Mississippi Today a notice of his intent to file a defamation lawsuit. The letter claimed that the newsroom’s CEO, Mary Margaret White, had defamed Bryant at a media conference by saying the former governor “embezzled” the welfare funds. One week later, White issued an apology for her remark, noting that Bryant had not been charged with any crime. Nevertheless, Bryant filed suit against White, calling her statement a “non-apology-apology.”

“[Now] I can’t even just say basic things about my reporting without the fear of legal retribution for statements that I know are accurate, and that I have a First Amendment right to say.”

– Reporter Anna Wolfe

Wolfe’s series showed how, during Bryant’s time as governor, federal funds intended to help Mississippi’s poorest citizens were rerouted to fund a volleyball facility, a horse ranch, and payments to a multimillionaire professional football player.

Bryant’s suits – now expanded to include Wolfe and the news site’s editor-in-chief – don’t address the alleged expropriation of funds on which Wolfe reported, Wolfe told CPJ. Instead, she said, their goal appeared to be to divert attention from the misappropriation of the welfare funds and prevent Mississippi Today from continuing to report on the story. As part of the lawsuits, Bryant’s legal team has also requested troves of private material from Mississippi Today and its journalists, including information about Wolfe’s confidential sources.

“[Now] I can’t even just say basic things about my reporting without the fear of legal retribution for statements that I know are accurate, and that I have a First Amendment right to say,” Wolfe told CPJ.

Mississippi Today reporter Anna Wolfe (left) won the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for her reporting on a welfare scandal. Two days later, former Mississippi Governor Phil Bryant started a number of legal actions that could endanger reporters’ First Amendment rights.

(Photos: AP/Rogelio V. Solis – left and right)

Mississippi Today appealed to the state Supreme Court against the lower court’s ruling directing them to produce material that could expose the identity of confidential sources, and is awaiting the Supreme Court’s decision before the libel case can proceed.

With Trump’s ascent on the national political stage, politicians around the country have grown more outwardly hostile toward the media, employing anti-journalist rhetoric, limiting access to government proceedings, and – when those tactics don’t stop criticism – using the courts as a means of retaliation in the face of unfavorable coverage. While many of these lawsuits amount to little more than saber rattling – Trump and his campaign have unsuccessfully sued major outlets for defamation, including ABC News, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and CNN – fighting them can have potentially devastating financial implications for local outlets with fewer resources.

The Wausau Pilot & Review, a small nonprofit news outlet in central Wisconsin, nearly went bankrupt from legal fees after Republican state senator Cory Tomczyk filed suit in November 2021 against the paper, its publisher, Shereen Siewert, and a reporter, for reporting that Tomczyk was overheard using a homophobic slur during a county board meeting. If it hadn’t been for a GoFundMe campaign to offset legal costs and national attention from a New York Times story, Siewert told CPJ, she’s not sure they would still be in business.

The legal battles – and the legal bills – continued for nearly three years as Tomczyk appealed the lower court’s decision to dismiss his libel suit against the paper. The state court dismissed his appeal in September 2024.

“There were periods of time when we thought, perhaps naively, that we wouldn’t see the kind of [libel] cases that threatened to wipe out a news organization,” said Bruce Brown, the executive director of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, a nonprofit organization that provides legal assistance to journalists. “We’re in a different phase now, and I think that plaintiffs see a road to success in libel cases in a way they didn’t 10 years ago.”

Kate Bolger, a First Amendment and media litigator who is a partner at the firm Davis Wright Tremaine’s New York office, said there are also increasingly serious threats to overturn the 1964 Supreme Court case New York Times Co. v Sullivan, which for decades has offered strong protections for the press by limiting the ability of public officials to sue for defamation.

Among those challenging the Sullivan standard are Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch, who have both urged the court to reconsider the Sullivan case and subsequent legal precedent built on the case, which could upend the current protections.

The importance of the outcome of these legal challenges in state courts should not be overlooked, said Bruce Brown, executive director of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. “Ultimately, I think this is where press freedom either prevails or is defeated.”

“This idea, which is kind of baked into how we think about defamation law, that the First Amendment is something different, that we should be wary of cases that involve free speech, has really kind of diminished,” Bolger said. Threats to the Sullivan case have in turn created an environment in which judges do not dismiss libel cases as quickly as they used to, leading to more protracted and costly legal proceedings, Bolger told CPJ.

Reporters also face vulnerabilities from other legal orders – notably, subpoenas demanding they turn over reporting materials, as in the case of Mississippi Today – as well as orders to third-party providers, such as telecommunication and tech companies, to turn over material that could expose details of journalists’ work, such as text and phone records.

By mid-September 2024, the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker had recorded at least 240 such cases since it began monitoring attacks on the press in 2017. In 2023, at least 35 subpoenas were issued against journalists in relation to their reporting, with another nine documented in the first eight months of 2024. The Tracker notes that the secrecy surrounding many of these cases means that the numbers are likely an underestimate. “Newsrooms don’t always want to bring attention to something they may need to comply with and, importantly, are sometimes legally obligated to not publicize a subpoena,” said Kirstin McCudden, the Tracker’s managing editor.

In one recent case that captured national attention, law enforcement bypassed the use of a subpoena altogether and used a search warrant to conduct police raids on the Marion County Record, a small newspaper in central Kansas, and the home of Eric Meyer, its co-owner and editor-in-chief. Following the raid, Meyer told CPJ that he has heard from other journalists around the country who faced similar pressures from local authorities. Lacking community support and financial resources, Meyer said those journalists were forced by “the bullies” to comply with pressures from law enforcement to self-censor or turn over reporting materials.

While laws and legal precedents protect confidentiality of doctor-patient and lawyer-client communications, there is no similar federal legal protection for communications between journalists and their sources, despite ongoing, decades-long efforts by organizations, including CPJ, to create a federal shield law.

In a rare move, a federal district court judge earlier this year held former Fox News reporter Catherine Herridge in civil contempt of court for refusing to divulge her source in a story about an FBI investigation. The judge’s decision cited limitations on the scope of the reporter’s privilege. Herridge faces fines of up to $800 for every day she does not divulge her source, though enforcement of the fines has been stayed pending her appeal in the case.

While 40 states offer some protection for journalists and their sources, as well as for their reporting materials, the state laws are a patchwork.

In Nevada, a state with some of the strongest shield protections in the country, the Las Vegas Review-Journal was caught in a year-long legal battle to protect decades of reporting material from being examined by local law enforcement investigating the murder of journalist German. The state Supreme Court ultimately recognized German’s reporter privilege, even after his death, but the legal battle was both costly and time consuming for the newsroom.

In contrast, Mississippi – one of the few states without a shield law – has relatively weak protections for reporters, leaving Mississippi Today and its staff vulnerable to penalties if they refuse to comply with a potential court order to turn over reporting material.

The importance of the outcome of these legal challenges in state courts should not be overlooked, Brown said. “Ultimately, I think this is where press freedom either prevails or is defeated.”

Police attacks on journalists

The shots came quickly, peppering the bodies of three photojournalists, Nicole Hester, Matt Hatcher, and Seth Herald, who were on the way back to their car just after midnight on May 31, 2020. The trio had spent the day in downtown Detroit covering some of the Black Lives Matter protests that erupted across the country after a Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd six days earlier.

They were laden with cameras and easily-visible press badges when two police officers stopped them several blocks away from the car. The journalists identified themselves as press, put their hands up, and complied with orders they heard to cross the street, Herald and Hatcher told CPJ days after the event. But as they crossed, they said, Daniel Debono, a police officer positioned approximately 50 to 75 feet away, fired rubber bullets at them, leaving angry welts on the journalists’ torsos and narrowly missing Hester’s eye.

At around 10 p.m. that evening, the Detroit police chief had declared an unlawful assembly and ordered law enforcement to disperse protesters from the city’s downtown, according to court records. The court documents state that when police encountered the photographers, the journalists had just observed a confrontation between police and a protester and had paused to observe and “potentially” take photographs. But Herald and Hatcher said they had stopped photographing and were on the way to the trio’s car when they encountered Debono and his colleague.

After the shooting, Hester said one of the officers told her, “Maybe you’ll write the truth some day, lady.”

When his initial shock had passed, Herald said that he was hopeful police would be held accountable for their actions.

But more than four years later, there has been little accountability. The felony charges against Debono were initially dismissed, but the dismissal was then overturned on appeal. Debono was arraigned in November 2023 on three charges of felonious assault, but the trial has not yet begun.

“Now, I just don’t believe in [accountability] at all,” Herald said. “You can see us standing in the video footage with our hands up. And he [Debono] still shot us. So it’s like, to me, that’s enough evidence. What else do you need?”

Hester, Hatcher, and Herald are among at at least 459 journalists who were physically attacked, hit with “less lethal” weapons, such as rubber bullets and teargas, or otherwise assaulted while covering protests that erupted across the country in the wake of Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, according to the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker. Of the 459 assaults against journalists that occurred in the four months following Floyd’s murder, the Tracker said police targeted journalists in at least 273 cases.

Within three months of Floyd’s murder, over 100 journalists were arrested or detained in what the Tracker described as an unprecedented show of aggression against the media. The overwhelming majority of these assaults were at the hands of police.

Journalists assaulted by law enforcement during this time have sued at least 44 times in civil cases, 13 of which are ongoing, and 22 class action suits, 16 of which are open.

The scale and violence of law enforcement’s response during the 2020 protests, documented by journalists across the country, prompted a national discussion about policing, including the way police interact with the media and what rights journalists have in protest situations.

“The press serves as the public’s eyes and ears, and if the press is removed completely from the scene, the public’s blind to what’s happening on the ground,” said Gabe Rottman, a senior attorney at the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, who helped lead the nonprofit organization’s response to police violence against journalists in 2020. “It’s really important that you have both policies in place that ensure journalists can continue to do their jobs [in protest situations] and a legal framework that protects their ability to do that,” said Rottman.

Photojournalist Olga Fedorova is arrested by police on August 20, 2024, in the midst of pro-Palestinian protests in Chicago during the Democratic National Convention. (Photo: Reuters/Adrees Latif)

Photojournalist Olga Fedorova is arrested by police on August 20, 2024, in the midst of pro-Palestinian protests in Chicago during the Democratic National Convention. (Photo: Reuters/Adrees Latif)However, there is no across-the-board set of policies and legal protections covering the right to report on protests, so journalists are left with the need to bring their own lawsuits to court to hold law enforcement accountable for wrongdoing.

California took a step toward changing that when civil society and media groups harnessed public outrage over the case of Josie Huang, a reporter for NPR member station LAist 89.3, who was assaulted and arrested by police while covering a 2020 dispersal of a protest in Los Angeles. The groups’ advocating successfully led to the enactment of Senate Bill 98, SB-98, which exempts journalists from police dispersal orders in the state.

Elsewhere, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) helped a group of journalists who were assaulted during the Minneapolis protests to sue the city. The journalists won a $950,000 settlement, though the city and police department did not agree to make reforms part of the settlement. And in New York City, a group of five photojournalists detained and assaulted by police during the Floyd protests reached a settlement that compelled the city police force to undergo media training and limited restrictions police can place on media access.

However, lawmakers in other jurisdictions have put new restrictions on journalists’ – and the public’s – ability to document police activity.

Indiana adopted a law in July 2023 that makes it a crime to approach an officer within 25 feet after being told to stop. The law is currently being challenged in court by a citizen journalist represented by the local ACLU chapter. The Reporters Committee, along with press organizations in Indiana, also sued to block the law; their suit is pending.

Despite these lawsuits and wider concern about the First Amendment implications of such restrictions, other states – notably Louisiana and Florida – have followed Indiana’s example, adopting laws that also restrict proximity to police. A similar law in Arizona was found to be unconstitutional by a federal judge after a group of media and civil society organizations sued the state.

The 2023-24 protests in the U.S. in response to the Israel-Gaza war offered hints of yet more shifts in the safety paradigm for journalists. As of late September 2024, at least 58 journalists have been assaulted and at least 42 detained, arrested, or charged at those protests, according to the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker, though in contrast with 2020, over half of these assaults were by private individuals, rather than law enforcement. The Tracker has not documented any lawsuits in relation to these assaults.

For photographer Herald, the police response to protests relating to the Israel-Gaza war was just further proof that little had changed since he and his colleagues were shot on the streets of Detroit in 2020.

“I think what happened to us in Detroit and to other [journalists] across the country in 2020 was [a] foreshadowing of what’s to come,” Herald told CPJ. “There are police departments across the country who face no reprimand, no repercussions for how they treat a journalist or protesters, who are entitled to their First Amendment rights. If you don’t reprimand the police force, what’s going to stop them from doing it again, or doing it worse than they did before?”

Global impact

November’s U.S. presidential election has been framed as an existential choice that will chart America’s future democratic course. The results will also have long-lasting global implications, including for freedom of the press and journalist safety abroad.

Over the past three decades, CPJ has documented how major policy shifts and the curtailment of civil liberties in the U.S. have been used to justify similar measures curbing press freedoms for journalists in other countries. Post-9/11 anti-terror laws in Morocco, for example, were used to shut down newspapers and detain journalists, while Russia began citing terrorism concerns to justify restrictions on critical reporting. Washington’s resurgent implementation of the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) in 2018 inspired other countries to approve “foreign agent” laws used to target journalists, and COVID-19 era attacks on “fake news” by then-president Trump seemed to set an example for authoritarian leaders trying to discredit media coverage in their own countries.

Brazilian journalists were deeply affected when their former President Jair Bolsonaro closely modeled his populist politics – including pointed anti-media vitriol and baseless claims of a stolen election that prompted an attack on the Brazilian legislature – after his U.S. counterpart.

“Bolsonaro was absolutely using Trump’s playbook, to the point where he was called ‘Trump of the Tropics’,” said Cristina Zahar Eggers, CPJ’s Latin America program coordinator, who served as executive director of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (ABRAJI) from 2018 to 2023.

Former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro speaks with the media on October 18, 2023, as he leaves the Federal Police headquarters after testifying about the January 8 riots, in Brasilia. Bolsonaro was known as ‘Trump of the Tropics’ for modeling his populist politics after his U.S. counterpart. (Photo: Reuters/Ueslei Marcelino)

Former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro speaks with the media on October 18, 2023, as he leaves the Federal Police headquarters after testifying about the January 8 riots, in Brasilia. Bolsonaro was known as ‘Trump of the Tropics’ for modeling his populist politics after his U.S. counterpart. (Photo: Reuters/Ueslei Marcelino) The former Brazilian president operated with the understanding that Trump’s behavior signaled a sort of carte blanche for populist leaders, said Eggers. During Bolsonaro’s time in office, ABRAJI documented a spike in violence against journalists, an increase in judicial harassment, and an uptick in online smear campaigns against reporters.

Roberson Alphonse, the head of national news at Le Nouvelliste, Haiti’s oldest newspaper, has closely followed U.S. politics since the days of former President George H.W. Bush. It’s a necessity, said Alphonse, given the outsized impact that U.S. policy can have on his home country, whose leaders – like those elsewhere in the world – look at the U.S. to “see if there is a green light” for actions such as calling journalists enemies of the people, as Trump has done.

“Those people who use that rhetoric are playing with fire – and they need to stop,” Alphonse said.

In contrast to the Trump campaign, which has shown no signs of deviating from the anti-media rhetoric of Trump’s first term, the Harris campaign is seen as likely to continue the Biden-era trend of a more civil relationship with the media.

The recent prisoner exchange between Russia and the U.S, which led to the return of Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich and Alsu Kurmasheva, a reporter for the U.S. Congress-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/ RL), as well as prominent Russian dissidents, was seen by some as a reassuring sign that the Biden-Harris administration cares about human rights, including freedom of the press.

By contrast, Trump’s ardent praise of Russian President Vladimir Putin sends a very dangerous signal, said Anna Nemzer, a journalist at the independent Russian station Dozhd TV (TV Rain) and a co-founder of the Russian Independent Media Archive project.

“The United States is a very powerful country with a very powerful president. If that president is somehow supporting Putin, it would negatively affect people who are protesting Putin and just trying to survive,” said Nemzer, who went into exile following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. Nemzer and scores of other Russian independent journalists were labeled “foreign agents” in retaliation for their critical reporting on the Russian government.

A journalist’s camera covered in dirt and broken glass lies on the back seat of a damaged car outside a hotel struck by Russian missiles in central Kharkiv, Ukraine, in January 2024. Ukrainian journalists are among those concerned about how the outcome of the US election could affect their work. (Photo: Reuters/Sofiia Gatilova)

A journalist’s camera covered in dirt and broken glass lies on the back seat of a damaged car outside a hotel struck by Russian missiles in central Kharkiv, Ukraine, in January 2024. Ukrainian journalists are among those concerned about how the outcome of the US election could affect their work. (Photo: Reuters/Sofiia Gatilova)While journalists in many countries worry primarily about the tone and the example set by the U.S. president, others are concerned that shifts in U.S. foreign policy positions more broadly would change their ability to report – and simply to live safely – in their home countries.

For Ukrainian journalists, shifting politics in Washington play an outsized role in their ability to work. Sevgil Musaieva, the editor-in-chief of the independent news website Ukrainska Pravda, said that the difference between Harris and Trump is the difference between having independent journalism in a country well-equipped in its fight for independence – or journalists working in a country critically weakened by a lack of U.S. support.

Musaieva, a recipient of a 2022 CPJ International Press Freedom Award, told CPJ of concerns about the effects on Ukraine’s media if Trump is able to carry out his threats to cut off the Biden administration’s military aid to Kyiv, Ukraine’s ability to continue defending itself against would be hamstrung – and any discussion about journalism could become moot.

“I remember the first days of the war and how it was scary and dangerous for journalists,” she said. “But for us, it’s not just about the ability to work. It’s about the ability to remain safe, for the country to remain safe.”

While there is a growing partisan divide over support for Ukraine, both Democratic and Republican parties have signaled that they plan to continue their support for Israel. For journalists in Gaza, this is seen as an indication that the harrowing conditions they have faced since the Israel-Gaza war began on October 7, 2023, are unlikely to improve regardless of the outcome of the election.

“There is a kernel of hope that a Harris administration could be slightly better. But I wouldn’t go as far as saying it will be hugely different,” Daoud Kuttab, a veteran Palestinian journalist and columnist with Al Monitor and Arab News, told CPJ. “I can’t imagine things getting worse for journalists in Gaza.”

A press-unfriendly White House could also affect U.S. government funding that plays a key role in supporting journalists and media outlets reaching vast audiences around the world. U.S.Congress-funded Voice of America, for example, recorded weekly global audiences of more than 350 million in 2023, and RFE/RL reaches more than 40 million people in 23 countries every week. Both platforms are overseen by the United States Agency for Global Media (USAGM), the federal agency established to provide uncensored news and information in countries where the press is restricted. The agency also subsidizes annual training for hundreds of media professionals around the world.

As president, Trump set his sights on USAGM, waiting two years for Congressional confirmation of his pick of loyalist Michael Pack as the agency’s CEO. Pack promptly took steps to force the agency’s long-autonomous networks to promote Trump’s “America First” agenda, tried to eliminate the “firewall” law guaranteeing editorial independence, and ordered investigations into journalists and coverage decisions. Pack’s agenda was stalled by lawsuits, and Biden removed Pack immediately after taking office.

Given these stakes, it’s hardly surprising that many foreign journalists are watching the Trump-Harris race with apprehension.

Conclusion

A Pew Research poll from April 2024 shows that 73% of U.S. adults say freedom of the press is extremely or very important to the well-being of society.

In a presidential race dominated by immigration, abortion, and other issues, that broad support probably won’t decide the outcome of the election. Nonetheless, the next person in the White House could determine whether independent media function as a cornerstone of U.S. democracy – including holding politicians accountable by fact-checking their claims and following up on their promises – or whether journalists will be at increasing risk from a fresh siege of legal and verbal attacks.

Harris alluded to the stark choice in her acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention, citing Trump’s “explicit intent to jail journalists, political opponents, anyone he sees as the enemy.” Though the Democratic nominee has not specifically focused on media freedom during her time as a presidential candidate, the party’s platform includes a section describing freedom of the press as “foundational to our nation” and explicitly rejects “Trump’s denigration of the free press.” Harris’ running mate Tim Walz cultivated a generally positive relationship with the press as Minnesota governor, notably apologizing to CNN reporter Omar Jimenez after the journalist and his crew were arrested during a live broadcast of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests in Minneapolis.

In contrast, the Republican Party platform makes no mention of freedom of the press, and Trump continues to blast critical media and individual journalists at campaign rallies and on social media, as he did throughout his four years as president. During his presidency, Trump praised a Montana Republican congressman for body-slamming a reporter, publicly mocked a disabled New York Times reporter, and regularly launched personal attacks against journalists, prompting Chris Wallace, then a Fox News anchor, to observe: “I believe that President Trump is engaged in the most direct sustained assault on freedom of the press in our history.”

Journalists watch the televised debate between Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump and Democratic candidate Kamala Harris in Philadelphia on September 10, 2024. (Photo: Reuters/Evelyn Hockstein)

Journalists watch the televised debate between Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump and Democratic candidate Kamala Harris in Philadelphia on September 10, 2024. (Photo: Reuters/Evelyn Hockstein)More recently, Trump has been accused of dismissing questions from Black reporters as “stupid” or “racist.” When a reporter asked Trump at the July conference of the National Association of Black Journalists, why Black voters should trust him, the former president responded, “I don’t think I’ve ever been asked a question in such a horrible manner. … You don’t even say, ‘Hello, how are you?'”

Project 2025, a policy agenda published by the conservative Heritage Foundation think tank and seen by many as a blueprint for a second Trump administration, contains proposals that would end public funding for NPR and the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) and dismantle or drastically overhaul the USAGM. While Trump has sought to distance himself from Project 2025, sections of it were written by former members of his administration, and the media plans are consistent with the former president’s efforts to defund public media and reshape the USAGM.

“In Trump’s first term, he tried repeatedly to roll back press freedom,” Joel Simon, founding director of the Journalism Protection Initiative at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism and a former CPJ executive director, in an August report for Vanity Fair. “And if elected once more, he will try, yet again, to go after the press.”

Through decades of tracking threats to freedom of the press around the world, CPJ has documented how the behavior of U.S. political leaders affects the realities faced by journalists, both domestically and abroad, on a local level.

Staff at the U.S.-based Haitian Times diaspora publication, for example, experienced an alarming escalation in racist harassment, online threats, and intimidation after Trump amplified Republicans’ debunked claims that Haitian immigrants were eating people’s pets in Springfield, Ohio. “The message is pretty clear that they [the harassers] know where we live,” the publication’s editor-in-chief, Macollvie Neel, told CNN after a hoax message sent police rushing to her home.

Politicizing and denigrating journalists, rather than respecting their watchdog role as the Fourth Estate, has a profound impact on democratic institutions and curtails the public’s ability to stay informed through trusted sources. The outcome of this November’s election will, in no small measure, determine the health of the media environment globally for decades to come.

CPJ’s letter to US presidential candidates

Against this backdrop, CPJ CEO Jodie Ginsberg has written to Trump and Harris asking them to affirm their support for fostering an environment in which media freedom is protected in the U.S. and overseas.

The letter called on the candidates to pledge to abide by the following principles:

- Adopt a respectful approach to engaging with journalists, with discourse and actions that promote journalist safety in public events, closed-door discussions, and online spaces, and eschew reprisal against journalists, while granting the media adequate access during the electoral campaign and into a new administration;

- Enact and enforce policies that effectively hold perpetrators of threats or violence against members of the media accountable to deter future aggression against journalists and media workers;

- Codify legal protections, such as the PRESS Act, for journalists in the U.S. to do their work without fear of surveillance from authorities, or forced disclosure of their sources in court, and refrain from using judicial processes to undermine the functioning of a free and vibrant press in the U.S.

- Promote press freedom and defend journalist safety through global diplomacy, recognizing journalists’ indispensable role in democracies worldwide. This effort includes working to free wrongfully detained journalists and securing justice for those killed in retaliation for their work.

The Harris campaign acknowledged receipt of CPJ’s letter, but neither candidate had signed the pledge by CPJ’s requested deadline of September 16.

(Editor’s note: This report has been updated to correct one of the locations from which AP photographer John Minchillo has reported and to clarify the role of Martin Reynolds in the Chauncey Bailey Project.)

Katherine Jacobsen has been CPJ’s U.S., Canada, and Caribbean program coordinator since 2021. She joined CPJ in 2017 as the news editor. Previously, Jacobsen wrote for The Associated Press in Moscow where she reported on nuclear waste dumping, climbing HIV rates among drug users, and Russia’s air campaign in Syria. She has also worked in Ukraine where she covered the Maidan protests, Crimea’s annexation, the separatist takeover of Donetsk, and reform efforts in Kyiv for outlets including Businessweek, U.S. News and World Report, Foreign Policy, and Al Jazeera English. Jacobsen has a bachelor’s degree in Slavic languages and literature from Northwestern University and a master’s of science in journalism from Columbia University. She speaks Russian and is proficient in French.

1 month ago

10

1 month ago

10