One bird bucks the stereotype of Australia’s raucous parrots – the mysterious and critically endangered night parrot (Pezoporus occidentalis). Rather than flying around in noisy flocks or eating fruit in trees, the night parrot roosts all day in a clump of sharp spinifex grass. When darkness falls, it scurries about on the ground to forage, almost like a little rodent.

For eight decades, we thought it might be extinct. But then, in 2013, it was photographed. Now we know this vanishingly rare nocturnal bird still lives in parts of the remote outback.

Because it’s so rare, it’s very hard to study. In our work in palaeontology, we recently identified some fossil leg bones as probably belonging to the night parrot. Because there were no modern skeletons to compare them with, we had to CT-scan a museum specimen.

What we intended to do was compare the leg anatomy to our fossil leg bones. But then we found something bizarre. The night parrot’s skull was wonky and the ears were asymmetrical. Predatory owls have this too, as a way to boost their hearing and hunt better. But why would a seed-eating parrot need superb hearing?

The night parrot is one of only two nocturnal parrots, alongside New Zealand’s kakapo. This 1890 illustration is by Elizabeth Gould, illustrator and wife of ornithologist John Gould.

Wikimedia, CC BY

The night parrot is one of only two nocturnal parrots, alongside New Zealand’s kakapo. This 1890 illustration is by Elizabeth Gould, illustrator and wife of ornithologist John Gould.

Wikimedia, CC BY

Of wonky skulls and offset ears

In our new research, we offer the first anatomical description of the night parrot’s skull. In this, we were fortunate to be allowed to scan the precious type specimen held by the Natural History Museum in London. This is the original skin used by John Gould, the preeminent 19th century English ornithologist, to formally describe and name the night parrot in 1861.

À lire aussi : Still here: Night Parrot rediscovery in WA raises questions for mining

We used high-resolution CT scans to look inside this museum “skin”, a dried specimen with internal organs removed, feathers on the outside and a partial skeleton on the inside.

The scans showed the left side of the skull did not mirror the right. Skull asymmetry isn’t unheard of in nocturnal birds. Many species of owl have offset ears and dramatically distorted skulls, which allows them to pinpoint any sound made by intended prey. But we certainly weren’t expecting it in a parrot.

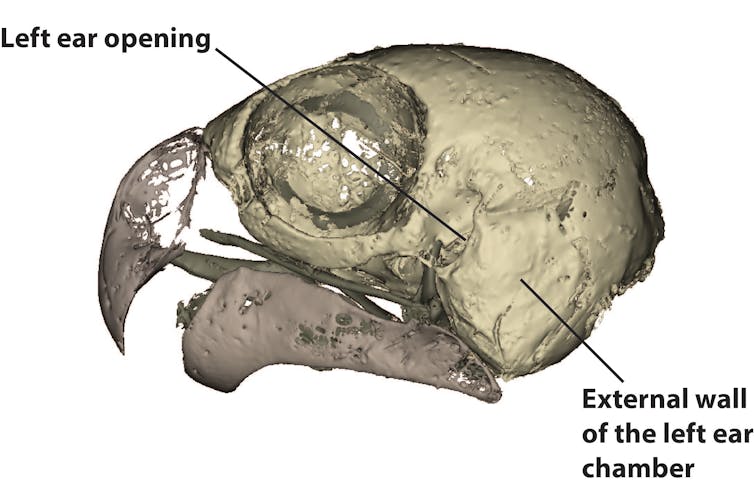

We CT-scanned the night parrot’s type specimen – and found something unexpected about its skull.

Mark Adams, copyright Natural History Museum, UK, Author provided

We CT-scanned the night parrot’s type specimen – and found something unexpected about its skull.

Mark Adams, copyright Natural History Museum, UK, Author provided

Wired for sound?

When we looked closely at the night parrot’s skull, we spotted telltale clues of a bird specialising in hearing. Asymmetry is part of it: the left ear opening is flat while the right one arches out to the side.

In uneven-eared owls, one ear is typically placed higher than the other. In flight, sound waves travelling from ground level hit each ear at slightly different times. This tiny difference in timing allows the owl’s brain to calculate precisely the sound’s origin on a vertical plane.

You can see the ears of the night parrot in this digital model created from a CT scan of the night parrot skull.

You can see the ears of the night parrot in this digital model created from a CT scan of the night parrot skull.

But night parrots don’t hunt fast-moving prey. They mostly eat seeds, so they probably don’t use asymmetrical ears to locate food.

While owl ears are positioned at different heights on the skull, this isn’t the case for the night parrot. The major difference between the parrot’s ears is how far they stick out sideways. This might help them locate the direction a sound comes from horizontally, which would make sense for a bird living almost entirely at ground level.

This could be useful to listen for predators, keep contact with their mates and young, find new potential mates, or to scan their habitat for competitors.

Adding to the evidence for excellent hearing is the size of this parrot’s ear chambers. Compared to other parrots, an unusually large volume of the night parrot’s skull is devoted to the external ear chamber – fully one third of the length of its head. These enlarged ear chambers may act like amplifiers, increasing the volume of sound transferred to the inner ears. This suggests it would be wise to keep the noise down in their habitat until we know more about their hearing.

Bigger ears, smaller eyes

A previous study found the night parrot has small optic nerves and reduced optic lobes in the brain for processing vision. From this, the researchers inferred the nocturnal parrot probably sees poorly in the dark. Despite this, it expertly navigates its dark world, flying up to a 30 kilometre round trip in a night to find food and water, before returning home to the same spinifex hummock where it roosts before sunrise.

Now that we’ve examined the skull, we can see the same clues. Vision appears to have been traded for hearing. Inside an animal skull, real estate is precious. Heads are heavy and cumbersome, and there’s only so much you can evolve to fit inside one. Enlarged ear chambers appear to constrain the maximum size of a night parrot’s eyes.

Even so, this bird has crammed in as much as it can. It has an outsized head compared to its body. Gould described the parrot’s “thick bluffy head” as one of the features defining the species.

When we measured the scleral ring – the circular bone supporting the eyeball – and compared it to other birds, we found telling differences. A night parrot’s cornea is about as small as it can possibly be while still allowing visually guided nocturnal flight. A millimetre or two smaller and they wouldn’t get enough light into their eyes to see in the dark.

This remarkable parrot is one of 22 threatened birds prioritised by the federal government for recovery. We hope ecologists can make the most of this to find out what we need to do to bring night parrots back from the brink. We’re only beginning to learn how unusual they are.

À lire aussi : Found: world's most mysterious bird, but why all the secrecy?

Elen Shute previously received a PhD scholarship from Flinders University and a fee-waiver scholarship via the Federal Government. She is employed by Flinders University and the Nature Conservation Society of South Australia.

Alice Clement receives funding from the Australian Research Council and is employed by Flinders University.

Gavin Prideaux receives funding from the Australian Research Council and is employed by Flinders University.

1 year ago

84

1 year ago

84