Mr. Mindbomb is a biography of Greenpeace co-founder Robert Lorne Hunter (1941-2005), told by his friends and family. The book was edited by Bob’s wife, 1970s Greenpeace organizer Bobbi Hunter. Scores of campaign and media colleagues contribute accounts of his life. A picture emerges of a man who deeply touched people’s hearts, inspired commitment, helped give birth to the modern ecology movement, and did it all with extraordinary humility and humour.

A Scots-Irish French-Canadian in London

Greenpeace activist Dr. Myron MacDonald traces Hunter’s family heritage to the Hunterston forests of Scotland, west of Glasgow on the Firth of Clyde. The epigram from the family crest, “Cursum perficio,” or “journey complete,” implies “I accomplish my purpose.” Bob’s brother Don tells of their father who one day stopped coming home, their modest childhood on the Manitoba prairies raised by their French-Canadian mother, Augustine Bernadette, and of Bob reading the newspaper to his mother after she lost her sight. He recounts their mother telling long, rambling stories and how Bob acquired the art of the raconteur. “The big difference was that Bob’s stories were funny,” Don recalls, “interesting, and more to the point. He learned the art of storytelling by improving on Mom’s style.”

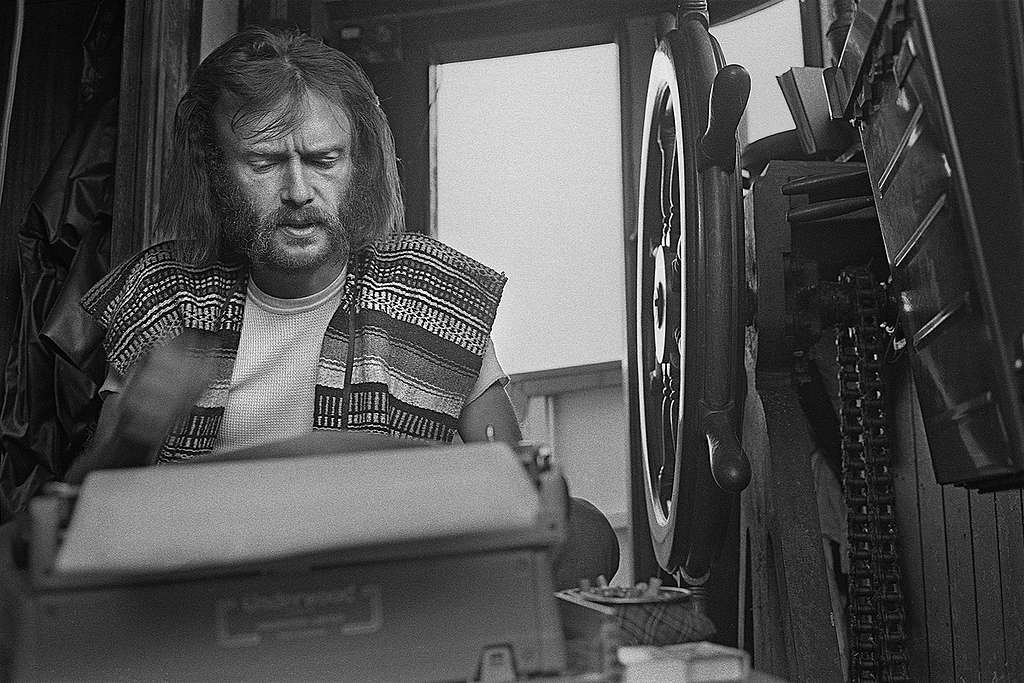

Bob Hunter became a writer as a child, creating his own illustrated books. He set off at age 19 to see the world, packing the typewriter that his mother had given him. Canadian-British physicist Walt Patterson describes meeting Hunter in London in 1962, hanging out in pubs with aspiring writers and living the bohemian life. “Bob was a virtuoso storyteller,” Patterson recalls, “with a vast repertoire, a rich and resonant speaking voice, and impeccable timing.”

In London, Hunter met Zoe Rahin, two years older and active in the peace movement. Zoe introduced Hunter to philosopher Bertrand Russell, a life-changing encounter, and Hunter followed Zoe and the renowned philosopher into the pacifist movement. In turn, Hunter inspired Walt Patterson to use his physics background to support the peace and ecology movements. In 1970, Patterson edited the UK’s first environmental magazine and in 1972 he represented Friends of the Earth at the UN Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm. “Before long I was a full-time and high-profile environmental campaigner,” writes Patterson, “all because Bob had triggered the spark … not only the information and insight he provided but also the burning ardour and headlong exhilaration he brought with it.”

Bob and Zoe married and moved to Canada, where Hunter worked at the Winnipeg Tribune, and their son Conan and daughter Justine were born. Justine Hunter, now a seasoned reporter at Canada’s Globe and Mail, picks up the story there, adding observations from her older brother Conan. She recounts a 1967 trip to Mexico in a Volkswagen van. On a remote desert road, they were pulled over by Mexican police, who concluded that the “penniless gringo in bare feet,” was a poor prospect for a fine or bribe. On the way home, everyone sick with dysentery, US border guards pulled apart the van looking for drugs. Conan’s last memory of Mexico was “the chrome trim of the headlights sitting on the dusty ground.” Zoe grew weary of Winnipeg winters and fled to Vancouver, and Bob soon followed. In 1968, Hunter published his first book, the coming-of-age novel Erebus, nominated for the Canadian Governor General’s Award, boosting his reputation in Canadian journalism circles. Justine explains that on the west coast Hunter “reinvented himself. The former clean-cut newspaper reporter from Winnipeg now sported long hair and a beard, promoted on billboards as the Vancouver Sun’s counterculture columnist.”

Greenpeace

Justine recalls how their modest East Vancouver home became a meeting place for Vancouver pacifists opposing US nuclear testing in Alaska. Conan recalls that, “Not only were they going to change the world, but they were forming the club that would do it.”

Rod Marining, working as a copy boy at the Vancouver Sun met Hunter in the newspaper lunchroom, and they became activist allies. Marining’s group Rent-a-Demo staged protests for worthy causes. “Bob was rising in respect and popularity,” recalls Marining. “I started to notice young people buying the newspaper and going right to his column. They had found an advocate in the Vancouver Sun.”

In 1971, Hunter published The Storming of the Mind, in which he introduced his idea of the “mind bomb.” Activism, he proposed, was not an “armed struggle” such as the storming images of the Bastille that will “explode in people’s heads … and change perception”, but rather a “communications struggle,” with the media as a “delivery system [for] mindbombs.” This idea would become a cornerstone of Greenpeace activist philosophy.

Bob Hunter at work on his typewriter.

© Greenpeace / Robert Keziere

Bob Hunter at work on his typewriter.

© Greenpeace / Robert KeziereIn the Vancouver Sun, Hunter wrote a column suggesting that the underground nuclear tests in Alaska might cause a tsunami that could hit the coast of Canada, and he made a placard that read “Don’t Make a Wave.” Irving and Dorothy Stowe — Quaker pacifists and US expatriates — proposed the group call itself the “Don’t Make a Wave Committee,” and they registered the organization as a Canadian charity. When Irving Stowe ended a meeting with the salutation “Peace,” ecology activist Bill Darnell added quietly, “Make it a green peace,” including the ecological crisis and creating a new image that would soon reverberate around the world. The group borrowed a Quaker strategy, proposed by Marie Bohlen, to sail a boat into the nuclear test site, and in 1971, Hunter joined this voyage, reporting for the Vancouver Sun.

I met Hunter at the press club and began working with the peace and ecology group, which in 1972 changed its name to the “Greenpeace Foundation.” After successful campaigns against US and French nuclear testing, Hunter wanted to stage a global scale environmental action, and we had begun to think about how to publicize forests, rivers, the toxins exposed by Rachel Carson, and the plight of other species. The big idea came to us from a cetologist from New Zealand.

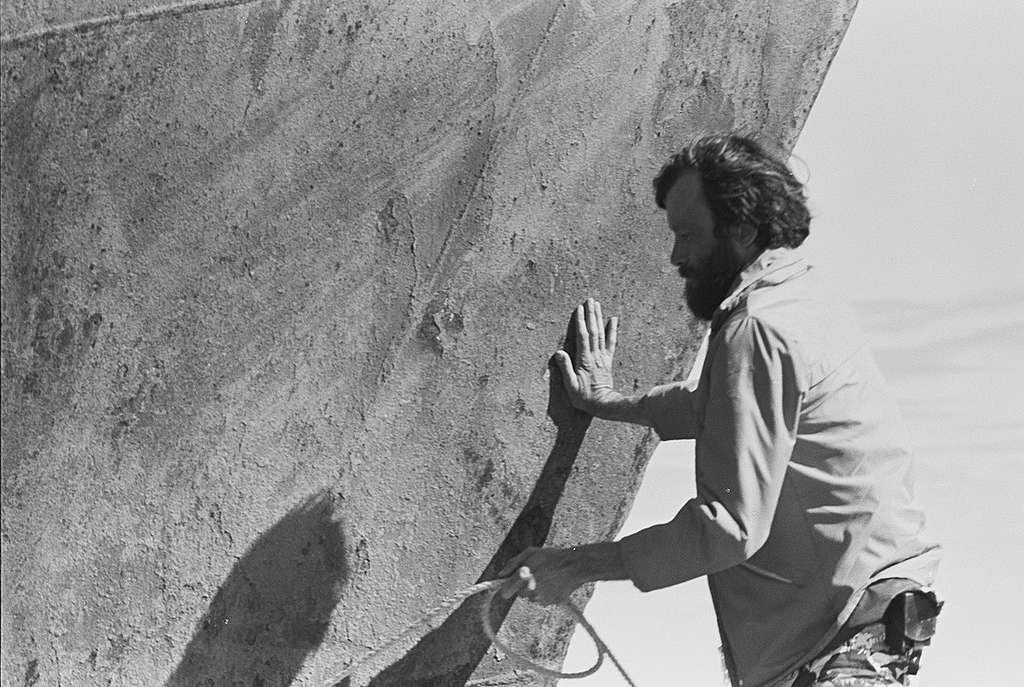

Dr. Paul Spong picks up the story here, telling how he approached Hunter in the spring of 1973 with the idea to “save the whales” using Greenpeace direct action and mindbomb tactics. “We met around the pool table at the back of the Cecil Hotel pub,” Spong recalls, “drank 25-cent beers, and plotted.” He tells of taking Hunter to the Vancouver Aquarium and introducing him to the Orca whale Skana, who playfully “seized Bob’s head in her mouth.” This experience — feeling both the power and gentleness of the whale — left Bob inspired and thoroughly committed. In 1975, we launched the first Greenpeace global ecology action, confronted Russian whalers in the North Pacific, and circulated the photographs and film around the world. Greenpeace had become a global ecology movement, and four years later, in 1979, we formed Greenpeace International, which now includes national and regional organisations in over 55 countries.

Bob Hunter, places his hand on the stopped Soviet harpoon ship in the Pacific near Hawaii. © Greenpeace / Rex Weyler

Bob Hunter, places his hand on the stopped Soviet harpoon ship in the Pacific near Hawaii. © Greenpeace / Rex WeylerStill communicating

In this book, Mr. Mindbomb, campaign colleagues from around the world — Carlie Trueman in Canada, Czech sailor George Korotva, Australian ecologist Chris Pash, and dozens more — tell of their adventures with Bob Hunter during Greenpeace campaigns. Bob never left Greenpeace in his heart, but he stepped away after the formation of a global organization and returned to journalism. Other friends and colleagues pick up the story after Bob’s Greenpeace career. Special education teacher Linda Weinberg tells of how she recruited Bob to help stop an LNG plant in Canada, and how he not only devised a protest plan and wrote media stories in support, but how he made the work fun and inspiring. The LNG plant was never built.

Media pioneer Moses Znaimer, a “Jewish refugee … born in Tajikistan,” and founder of Canada’s CityTV and scores of popular television shows, channels, and stations, hired Hunter to be “the world’s first ecology reporter.” He describes Hunter as “a philosopher of depth and foresight … demonstrating a crazy combination of recklessness and courage. … Bob Hunter didn’t have to hector or browbeat or command, because he could persuade, and what he achieved is far greater than being the founder of a company.” Znaimer writes, ” Hunter galvanized millions in defence of the planet.”

Janine Ferretti, a Professor of Global Development Policy at Boston University, tells how Bob helped her husband lobby politicians for sound ecological policies. She tells how, after Bob’s passing, that she began using his 2002 global warming book, 2030: Thermageddon, with her students. “Bob cut through the complexity of climate science and the noise of climate politics,” she writes. “With his trademark of hard facts, flawless logic and effortless clarity, Bob Hunter asked a new generation to take a stand and to act … I was moved to hear my students reflect on his writing, and I witnessed that, years after his death, Bob is still communicating and inspiring.”

Elizabeth May, former executive director of Sierra Club Canada and Canada’s first Member of Parliament from the Green Party, writes an Afterword, and environmental activist and Sea Shepherd founder Paul Watson writes an Introduction to the book. Editor Bobbi Hunter describes her husband’s message as: “Follow your heart and start walking in any direction, change will happen … any single person can make a difference. Just do something.”

Bob and Bobbi Hunter on board the James Bay entering San Francisco Harbour. © Greenpeace / Rex Weyler

Bob and Bobbi Hunter on board the James Bay entering San Francisco Harbour. © Greenpeace / Rex WeylerBob’s daughter, Emily, embraces the sad but noble task of describing her father’s passing on May 2, 2005, “with his family surrounding him just as he’d wished … We each ceremonially took turns speaking to him and telling him what our love for him meant and gave him permission to let go of this plane of existence. My father taught me a lot about the macro stuff that matters – the planet’s well-being, our collective well-being, independent thinking, and interdependent relationships – but most of all he taught me to love.”

Fourteen years later, her first son was born on May 2, the anniversary of her father’s death. She and her husband Ryan Dyment named the boy Phoenix. “The world we know today is dying,” writes Emily. “But in that same breath, a new world is being born (or reborn). I don’t believe my father is still here. Instead, I believe my father’s spirit had to pass from this realm, perhaps into another. Yet I can’t deny that there is something here – something bigger that my father’s spirit was a part of, that is instilled in me, and now is instilled in my son.”

I last spoke to Hunter by phone, from his hospital bed in Mexico, where he was fighting the cancer that finally took him. He made a comment that still reminds me of his devotion to realism, his upbeat spirit, and his uncanny ability to discover the humour in everything: “Hey, Rex,” he exclaimed cheerfully, “I found out today that my blood type sums up my life’s philosophy!” Yeah, what’s that, Bob?, I asked. “B-positive!”

Bob Hunter plays a flute on the deck of the Phyllis Cormack during the 1975 whale campaign. Off the Canadian coast. © Greenpeace / Rex Weyler

Bob Hunter plays a flute on the deck of the Phyllis Cormack during the 1975 whale campaign. Off the Canadian coast. © Greenpeace / Rex WeylerMr. Mindbomb: Eco-Hero and Greenpeace Co-founder Bob Hunter

Edited by Bobbi Hunter

April 2023

1 year ago

80

1 year ago

80