Journalists are collaborating to tell the stories of the Amazon, and what is happening in the region’s rainforests. Image: Shutterstock

The vast interconnected rainforest basins fed by the giant river systems of the Amazon and the Orinoco are at the center of the global crisis of economic degradation and global warming.

For the media, it’s a challenge that’s both critically transnational and profoundly local. To manage the crisis, local media from Venezuela and Brazil are forging alliances to meet the moment as too much of the established media — captured by state-aligned interests — fall short.

Two almost simultaneous events have threatened to hurry on the destruction of this globally critical region: the regime in Brazil of the right-wing Jair Bolsonaro and the creation in Venezuela of the Orinoco Mining Arc by the government of Nicolás Maduro.

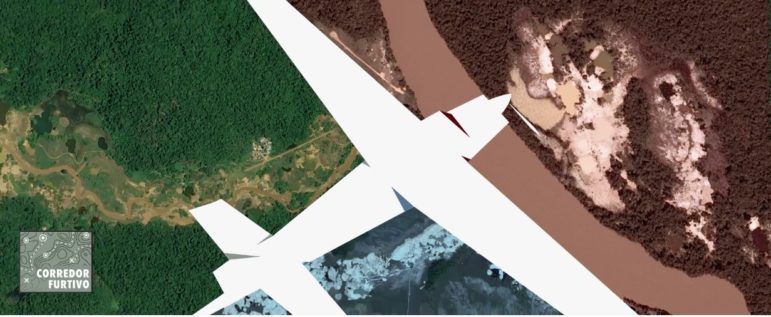

Read GIJN’s behind-the-scenes story about the Corredor Furtivo series, which investigated illegal mining in Venezuela.In Venezuela, as traditional media became captured by the governments of former president Huge Chavez and Maduro, journalist-run new media outlets turned to collaborations to cover the hard-to-report stories of environmental degradation and corruption, particularly in the large Orinoco Mining Arc in the country’s southeast.

The leading digital news organizations, Runrun.es, El Pitazo, and Tal Cual, formed a network with the Star Wars-inspired name La Alianza Rebelde Investiga (ARI) to share content and resources, while the investigative portal Armando.info cooperated with Spain’s El País, the Pulitzer Center, and Earth Rise Media to produce the special report Corredor Furtivo.

Independent local media are getting into the act, with Ciudad Guayana’s El Correo del Caroni working with Runrun.es, the Netherlands’ De Correspondent and the Miami Herald/El Nuevo Herald, the Pulitzer Center, website ProDavinci.com from Caracas, and the investigative platform InfoAmazonia.org, from São Paulo, Brazil.

In ARI’s Canaima: A Paradise Poisoned by Gold, Lisseth Boon and Lorena Meléndez, from Runrun.es, took to a curiara (a dug-out canoe) for several days to navigate the Carrao river upstream in Canaima National Park.

Local media from Venezuela and Brazil are forging alliances when the established media falls short.Canaima used to be a relatively contained tourism paradise, but the Venezuelan crisis almost wiped out the activity and some Indigenous people took up mining. In a 36-hour journey, Boon and Meléndez managed to count 21 rafts with mining dredges in the rivers of Canaima. The mining technique involves dredging earth from the riverbed and extracting gold using mercury, which is then dumped into the river or evaporated in the air.

Mining in rafts was legalized in seven rivers by the government. The journalists found the blackwater being muddied as primitive mining was destroying topsoils, filling rivers with sediment and mercury. The journalists even became stranded on the sandbanks being produced.

They found, too, that gold mining had crept into the western part of this national park. It’s dividing the Indigenous Pemón between those for or against mining. It’s enriched a hotel entrepreneur who has planes to smuggle the gold to the Netherlands Antilles, and who has turned his luxury tourism camp into a base for the Venezuelan military.

Along the course of the Caroní river, patches of devastated land look like beads in a rosary strangling the national park. The crystalline blackwaters have turned brown and murky. Downriver, the water enters the massive reservoir of the Guri dam, one of the largest in the world, which produces 70% of the country’s electricity and powers basic industries in Ciudad Guayana. Sedimentation, mercury, and heavy metals are retained in the reservoir and jeopardize its operation.

Image: Screenshot

Armando.info’s collaboration, Corredor Furtivo, turned to satellite imagery and artificial intelligence to pinpoint 3,718 points of activity and 42 makeshift landing strips. They also tracked the activities of armed groups in the states of Amazonas and Bolivar. Invading ELN guerrillas and FARC dissidents are attempting to recruit young Venezuelan Indigenous people, some of who are in turn organizing into armed self-defense groups.

The work, coordinated by Joseph Poliszuk and Javier La Fuente, found that “the proportion of forest affected and the speed of deforestation in Venezuela surpasses any precedent in the Amazon region” and that while the Venezuelan part of the Amazon, makes up only 5.6% of the total area, it contains 32% of all illegal mines in the biome of the Amazon-Orinoco basin.

The work carried out by all these media groups has helped the story break through globally, raising international awareness and serving as a critical information source for the September 2022 report of the United Nations Fact-Finding Mission reflecting the dramatic situation in the Venezuelan Amazon.

Prioritizing Environmental Stories

With its priority on the environmental crisis, the São Paulo-based portal InfoAmazonia has grasped the importance of transnational collaborations to cover the whole of Amazonia, participating in projects linking journalists and media from Brazil, Venezuela, and Colombia.

It’s a complex and shocking evolving story. As a report in partnership with the Colombian newspaper El Espectador, on the activity of mining rafts in several rivers in Colombia and Peru, found: “Parents have to decide ‘whether the little ones are going to get sick with mercury in 20 years or go hungry tonight.’”

InfoAmazonia looks for linkages beyond the region, too, looking into mercury smuggled into Brazil via Bolivia from Mexico, Tajikistan, the United Arab Emirates, and Russia. They also produced a documentary about the mercury trade in Guyana.

InfoAmazonia received the King of Spain Journalism Award in 2022 for its work on air pollution caused by forest burning in the Amazon and its impact during the COVID-19 pandemic. In an interview prior to the ceremony, editorial director Juliana Mori stated that forest loss increased under the presidency of Bolsonaro.

“It’s has been a time of many incentives for environmental crimes,” she said. “In 2019-2020 the burnings during the dry season have been more than in a decade.” In 2021, Brazil was by far the country that destroyed the largest area of primary forest, with 1.5 million hectares, getting dangerously close to the 20% of forest cover that would mark the point of no return, when the shift of the planet’s largest rainforest into dry savannah becomes inevitable.

Cooperation between media to report the growing crisis in the Amazon biome has only just begun. “I think that these alliances,” says María de los Ángeles Ramírez of El Correo del Caroni, “like the one we had with InfoAmazonia, are now going to expand because the problems are already regional, they are not going to stay local.”

This article was first published by the International Press Institute and is republished under a creative commons license. You can read the original here. The text has been lightly edited for style.

Additional Resources

Abraji: 20 Years Fighting for Investigative Journalists and Journalism in Brazil

My Favorite Tools: How Rafael Soares Investigates Police Killings in Rio

My Favorite Tools: Geo-Journalist Gustavo Faleiros

Andrés Schäfer is a Madrid-based freelance researcher and journalist. This article was written as part of a series profiling innovative local news publishers. The series — the IPI Local Media Project — is telling the stories of how local media around the world are reinventing everything to better serve their audiences and fulfil their key role in democracy.

is a Madrid-based freelance researcher and journalist. This article was written as part of a series profiling innovative local news publishers. The series — the IPI Local Media Project — is telling the stories of how local media around the world are reinventing everything to better serve their audiences and fulfil their key role in democracy.

The post Telling the Stories of South America’s Giant River Basins appeared first on Global Investigative Journalism Network.

1 year ago

70

1 year ago

70