Recently, the states of Oregon and Massachusetts have proposed delaying enforcement of state truck engine emissions standards originally put in place to protect the health and welfare of their residents, standards stronger than what is enforced by EPA at the national level, and we’re seeing truck manufacturers push for even more delays around the country. The rationale for this delay is largely based on industry disinformation, with manufacturers choosing to gin up anxiety among truck dealers to wage a war on the regulations by proxy. We heard this all in full effect at recent meetings of the California Air Resources Board (CARB) and Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, where some in industry advocated for delays all the way out to 2027.

This path taken by industry is a game of chicken with the regulators, a refusal to comply with the regulations as they stand and a dare to enforce them. Below, we walk through this cynical industry action and why it’s critical that regulators hold firm in the face of this market manipulation. Lives are on the line.

Industry is compliant with state regulations and agreed not to oppose them

There are two separate state regulatory actions that manufacturers are fighting at the moment, the Advanced Clean Truck (ACT) rule, which requires an increasing share of electric trucks to be sold, and the Heavy-duty Omnibus (“Omnibus”) rule, which requires new heavy-duty engines achieve a 75 percent reduction in health-harming NOx emissions, on average, compared to the current federal standards that have been in effect since 2010.

California is the only state in which those standards are in effect in model year 2024, and manufacturers are overcomplying with both standards at this time, thanks in large part to electric truck sales that well exceed what is required by ACT and flexibilities in the Omnibus rule that were agreed to with the manufacturers.

Truck manufacturers, however, are now throwing a temper tantrum behind the scenes in order to try to renegotiate a rule they promised to follow. Because they’ve agreed not to oppose adoption of these standards, they are waging that war by proxy, pushing dealers to oppose the regulations through lies and market manipulation. The dealers themselves made clear they are feeling the pain of these actions and are struggling to fight back against the manufacturers, embodied best in a plea from one dealer to CARB at the recent hearing to get the manufacturers to “act in the spirit of the Clean Truck Partnership agreement and stop putting politics ahead of public services.”

Truck makers are manipulating the market with draconian rules

In order to gin up anxiety among dealers, manufacturers are wreaking havoc on state truck sales by putting the burden for compliance exclusively on the backs of dealers and ignoring the many flexibilities in the regulation aimed to reduce compliance burdens. Such tactics represent a new anti-regulatory approach to compliance that seem more like a political statement than sound business strategy.

This tactic only makes sense if the goal is not to comply with the regulation but to maximize the pain felt by dealers. And, because increasing a company’s compliance costs is bad for business, this strategy is dependent upon one’s competitors also pursuing this uneconomic strategy. Incredibly, that is exactly what appears to be happening, a fact highly suggestive of collusion among the truck manufacturers.

So what exactly are they doing? Rather than working with dealers as required by the Clean Truck Partnership and as one would expect from a good faith effort to comply with the law, manufacturers are instead enforcing quotas that have absolutely no grounding in either regulation. Manufacturers are requiring dealerships to purchase a specified number of electric trucks before receiving any allotment of diesel-powered vehicles, even in applications for which there is no electric vehicle availability. This behavior, known as ratio-ing, has resulted in massive decreases in in-state truck sales, including (according to the California New Car Dealer Association) an 80 percent year-over-year decrease in Class 8 vehicle sales, the heaviest and biggest on-road vehicles. This ratio-ing behavior is not required by ACT and is instead a choice by manufacturers to manufacture a crisis and build pressure on regulators to delay pollution rules.

Importantly, manufacturers are lying to their dealers about the origin of this artificial product shortage. According to interviews with dealers and manufacturers, sales representatives are telling dealerships that limited product availability is being driven by compliance with ACT regulation. However, representatives from the same manufacturers have explicitly told regulators (accurately) they are well-situated to comply with ACT.

ACT does not require a specific share of any given application be electric—rather, compliance is based on the average of a manufacturer’s entire portfolio. This allows manufacturers to prioritize electric truck sales in the vehicle markets that are most advantageously deployed.

The voluntary decision by manufacturers to withhold sales from its dealers via ratio-ing is simply part of a strict, non-regulatory, and nonsensical business plan.

Truck makers are pursuing high-cost compliance to burden dealerships

Ultimately, it is the manufacturer that determines product availability, and it is critical to re-emphasize that the shortage felt by dealers is a crisis manufactured by truckmakers. This was reiterated by CARB at a recent meeting, and the dealers themselves confirmed this as well through their own testimony about sales restrictions. The lack of available trucks is fully within manufacturers’ control and comes directly as the result of business malpractice.

Manufacturers comply with ACT and the Omnibus through credits. For ACT, there is a minimum number of zero-emission trucks a manufacturer is required to sell—if they sell more than is required, they can bank those credits to offset future obligations, and if they fall short they need to either draw upon any bank they may have built up or purchase vehicle credits from manufacturers that have exceeded their obligations. The Omnibus works in much the same way, but with credits tallied in tons of emissions. Under both rules, there is an excess of available credits, particularly from the growing number of all-electric truck manufacturers that naturally exceed the requirements of both rules.

As we heard repeatedly during the CARB hearing, manufacturers are refusing to engage in the credit market. As in the case of ratio-ing, this artificially increases their costs of compliance but also naturally increases the pain felt by dealerships. Manufacturers are price gouging on the electric trucks they do sell, with costs nearly $90,000 per truck higher in the US than a comparable EV goes for on the European market, and then in markets where such trucks aren’t available, manufacturers are unwilling to compensate by using the flexibilities available. As Trevor Gasper of Thor Industries, an RV manufacturer that looks to truck manufacturers to supply chassis on which to build RVs, “These manufacturers are not interested in purchasing credits to assist the RV industry.”

Exiting an entire market segment because of self-imposed restrictions is certainly a choice, but it’s not a very smart one. And it’s one that flies in the face of industry sustainability commitments.

Truck makers have manufactured a crisis despite product availability

Of course, credits are meant as a temporary fallback—in the long run, it’s more cost-effective to simply comply with the regulations yourself. And in fact, that’s exactly what we see. Manufacturers have used their credit bank to buy time to supply product. While they certainly could have made some of these products available more quickly and, in some cases, have such compliant products available overseas, there is no doubt that manufacturers are preparing right now to comply without credits.

PACCAR was the first to certify its 13L heavy-duty diesel engine to the CARB 2024 standards, but Volvo introduced its own compliant engine shortly thereafter. The reason why they were able to do so is that 2024 compliance doesn’t require massive investment or timelines, as Volvo themselves noted: “Really, the D13 is the same engine on the inside. (The CARB-complaint D13) is more about the turbo and then the enhanced aftertreatment system, and the 48-volt alternator.” Cummins, the largest engine manufacturer, noted in recent comments to CARB that while they have not yet certified a diesel engine to these standards without credits, “This summer we added another engine family to our 50 mg [CARB-compliant] lineup, and we are on track for additional medium- and heavy-duty 20-50 mg engine families in 2025, 2026, and 2027.”

The question of product availability isn’t whether or not manufacturers can meet the rules on the books—it’s how they approach meeting them. And right now they are choosing to ignore all the available flexibilities that lower costs in an effort to undermine the regs themselves, punishing dealers in the process.

Tallying up the harm

If state regulators grant delays in these regulations by capitulating to this manufactured crisis, they are granting truck manufacturers exactly what they have set out to do, and they are doing so on the backs of those who these regulations were meant to protect. Every delay, every carve-out, every weakening made by regulators at the behest of industry has a direct and permanent cost on the health of residents around the country.

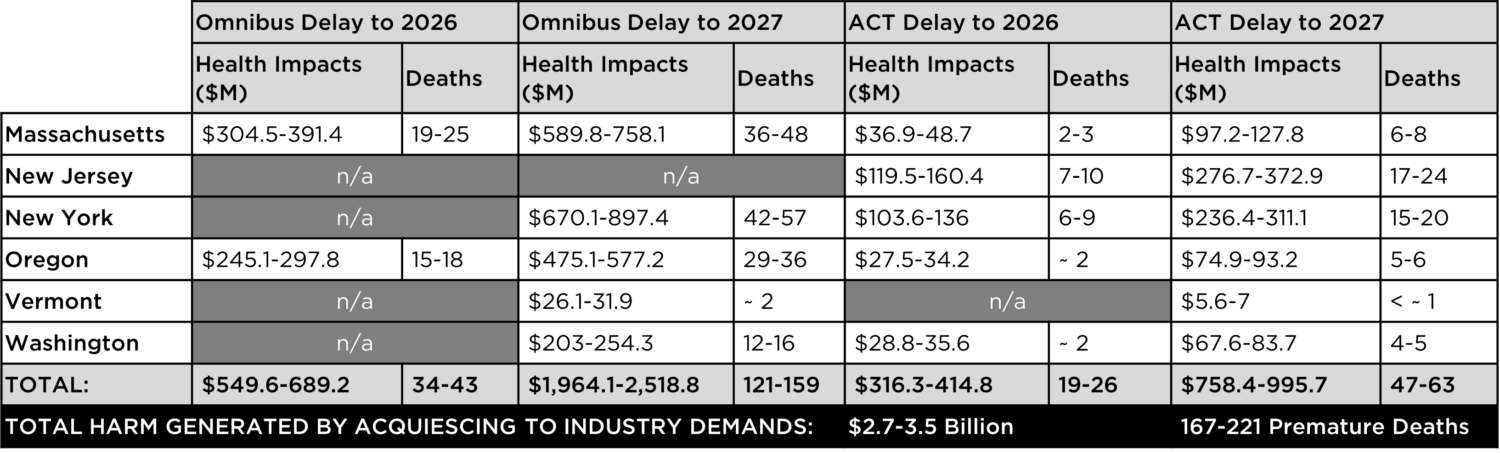

The table below tallies up the harm from delaying these rules, as Oregon and Massachusetts have proposed, as we continue to see industry support for similar action in other locales. There are lives at stake, as evidenced by UCS modeling.

Industry’s push to delay state clean truck regulations until 2027 would result in up to $3.5 billion in monetized health impacts from ER visits, school days lost to asthma, etc. Part of these harms would be the premature deaths of up to 221 individuals, the result of additional pollution from delaying these critical regulations.

Industry’s push to delay state clean truck regulations until 2027 would result in up to $3.5 billion in monetized health impacts from ER visits, school days lost to asthma, etc. Part of these harms would be the premature deaths of up to 221 individuals, the result of additional pollution from delaying these critical regulations.Regulators should ensure communities benefit as intended

Industry has engaged state regulators in a game of chicken, and for the health of communities around the country, it’s critical that regulators not blink. Afterall, trucking industry disinformation is nothing new: this is just the latest example. But, if any agencies choose to weaken these rules through delay or carve-outs, they must ensure those emissions reductions still happen.

There is already a mechanism in place to do this in the Omnibus rule—as part of the Clean Truck Partnership, California negotiated an extension of a “legacy” provision that allows the sale of non-compliant engines in exchange for commensurate emissions reductions through designated projects meant to benefit disadvantaged communities, such as replacing dirty diesel locomotives with cleaner alternatives or deploying electric charging infrastructure. This is a poor replacement for compliance, but it at least makes an attempt to mitigate the harm caused directly by manufacturers, and on their dime.

Manufacturers have broken the rules with artificial caps that undermine the regulations. Regulators should hold firm on these rules to force industry’s hand, but if they’re going to fold, they better make sure industry pays for the harms caused by such market manipulations and ensure the communities suffering from diesel pollution aren’t the ones paying with their health.

3 weeks ago

45

3 weeks ago

45