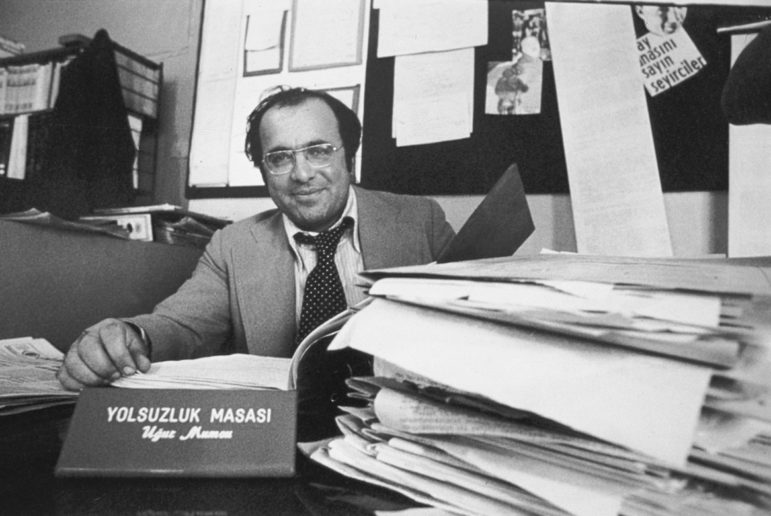

Uğur Mumcu was a legendary Turkish investigative journalist and longtime columnist, whose assassination in 1993 shocked the country. The journalism foundation that bears his name seeks to keep the legacy of watchdog reporting alive in his home country. Image: Courtesy of um:ag

On a snowy day in January, 1993, the residents of Karlı Street in the Turkish capital Ankara were shaken by an explosion. A car was blown up by a bomb placed underneath it. The street filled with blood, the snow turned red.

The assassination of Uğur Mumcu — the standard bearer for investigative journalism in Turkey — was a shock to the whole country.

For years he reported on drug and gun smuggling, fictitious exports, Islamic fundamentalism, and the Kurdish separatist movement, always with endless tenacity, attention to detail, and consistently compelling evidence to back up his stories.

He was also the star columnist of the widely respected Cumhuriyet newspaper for almost twenty years. “Uğur Mumcu’s first big investigation — The Furniture Files — was the most important example of investigative journalism at the time,” says media expert and journalist Can Ertuna. The investigation shed light on the shady businesses of Yahya Demirel, the nephew of the Turkish prime minister at the time, who had received millions of liras worth of tax refunds from fictitious exports.

“My father was receiving constant death threats… for the last three years before his assassination, he was wearing body armor.” — Özge MumcuOf course, defamation lawsuits followed the story’s publication, “but even the prime minister couldn’t change the outcome of the lawsuit because of the extensive amount of evidence Mumcu collected,” Ertuna says. Yahya Demirel was later tried for tax fraud and found guilty.

Mumcu was a prolific writer and his book “The Pope-Mafia-Ağca” is considered to be a masterpiece of watchdog journalism in the country. The book is an investigation into Mehmet Ali Ağca, who shot and wounded Pope John Paul II in 1981 and murdered Abdi İpekçi, the editor-in-chief of Milliyet newspaper.

The book sheds light on many details of Ağca’s ties to the rightwing Grey Wolves (Ülkü Ocakları) organization, and reports that he had links to the Turkish mafia, was involved in drug and arms trafficking, and had ties to various intelligence organizations. Despite constant threats, Mumcu never stopped reporting the facts, dedicating himself to the public good despite the dangers.

“My father was receiving constant death threats,” his daughter Özge Mumcu remembers. “For the last three years before his assassination, he was wearing body armor.”

Before his murder, Mumcu was researching the alleged links between Turkey’s National Intelligence Organization (MIT) and the terrorist organization the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). Even though 30 years have passed since his assassination, the people responsible for Uğur Mumcu’s death have never been brought to justice.

Turkey’s ranking on the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index has fallen nearly 50 places since 2007, to 149th out of 180 in 2022. Image: Screenshot /RSF

In Turkey, journalism was — and still is — a dangerous profession. In 2022, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) ranked the country a dismal 149th out of 180 for press freedom, falling nearly 50 places down the ranking compared to 15 years prior. Under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who became prime minister in 2003 and then president in 2014, journalism in Turkey has been undermined, censored, and attacked in numerous ways. “With 90% of the national media now under government control, the public has turned, during the past five years, to critical or independent media outlets of various political persuasions to learn about the impact of the economic and political crisis on the country,” RSF noted in its latest annual report.

Hope from Despair

After he was killed, Mumcu’s daughter Özge and her family founded um:ag — the Uğur Mumcu Investigative Journalism Foundation — hoping to pass on Mumcu’s investigative approach to new generations and to show the world that “killing is not the end.” Um:ag provides training, workshops, and investigative journalism education through scholarships for young graduates under 25 years old, preparing them to follow and question the news in Turkey and the world.

Özge Mumcu, 41, has a Ph.D. in Political Science and has been working full-time for the foundation for the last 14 years. “It is who I am,” she explains. “They tried to silence him by taking his life, but with this foundation, we are keeping my father’s voice alive and working to make it even louder.”

Her father was often described as a “one-man army” by people close to him because of his fearless fight for the public good. Um:ag aims to train investigative journalists who can carry on that battle, regardless of their political beliefs — a vital task in a dangerously polarized country.

The foundation has already trained hundreds of people — some have even become stars of the genre. Many investigative reporters in Turkey today started their professional careers thanks to um:ag’s training.

Kemal Göktaş is one of them. Just like Uğur Mumcu, Göktaş graduated from the Law School of Ankara University.

Kemal Göktaş is one of many Turkish reporters who has benefited from um:ag’s journalism training courses. Image: Courtesy of Göktaş

“I admired Uğur Mumcu and his work. He was a childhood hero to me,” recalls Göktaş, although he adds that he had very different political beliefs than the slain journalist. “Nonetheless I kept reading him every day. I had enormous respect for the work he was doing.”

That is why he didn’t have high expectations when, one night, his roommate gave him the application form for the six-month-long um:ag journalism course and encouraged him to apply. “I didn’t have much hope, because I thought the foundation would make its choices on an ideological basis,” Göktaş admits.

He was pleasantly surprised to be accepted and in the 20 years that followed his training he has written two books and many investigative reports on political assassinations, terror attacks, conditions in prisons, and women and children’s rights.

The investigation he is most proud of is The Document That Will Shake Turkey. It did what it promised to do. His reporting revealed that Turkey’s National Intelligence Organization (MIT) was taking steps to obtain the transcripts of telephone communications of all telecom companies in the country. This bombshell report caused a huge stir and won him the country’s most prestigious press freedom award. In retaliation, the government tried him for allegedly “acquiring classified information.” (He was subsequently acquitted.)

Göktaş has been granted many other prestigious awards for his investigations and believes that none of this would have happened if it wasn’t for um:ag’s training program.

“If it wasn’t for the foundation, I wouldn’t be a journalist today.” — Turkish investigative journalist Ali Çelikkan“We were given theoretical training for three months and internship opportunities in a media organization for another three months,” he explains. “The training was incredibly substantial and prepared me very well for my career. It provided us with a critical perspective on the media, but it was also very practical.” He thinks that the program should be a model for faculties of communication studies in Turkey.

Ali Çelikkan is another example of how um:ag has shaped a journalist’s career. Now based in Berlin as a freelance reporter, Çelikkan contributes to the German newspaper TAZ among other media outlets. At the beginning of 2022, Çelikkan published his latest investigation, on the activities of the Turkish far-right in Germany. His target? That same extremist group, called the Grey Wolves, that Mumcu once investigated.

“I started journalism thanks to um:ag,” Çelikkan says. “Not only did I learn how to write news there, I also took classes from extraordinary people in many fields, from law to energy policy, from history to politics. If it wasn’t for the foundation, I wouldn’t be a journalist today.”

Serving a Unique Role

Um:ag has a unique position within Turkey. Decades after the foundation was created, it is still training investigative journalists in today’s polarized media environment. Özge Mumcu says the media landscape has changed over the years in Turkey, and many big media outlets have closed, changed hands, or lost their independence and critical stance towards the government. Despite this, she says “um:ag has never changed its essence… it has put investigative journalism at the forefront of every issue.”

That the legacy of Uğur Mumcu continues on through the work of um:ag is that much more important because of how different the press environment inside Turkey is today, Ertuna points out.

“Mumcu was an extraordinary, well-educated, qualified journalist who did not hold back in his investigations and who clearly overcame a wall of fear,” he says. “However, I think it is crucial to mention that he operated in a media climate that provided him with the space he needed. The journalism of his time in Turkey was evaluated by journalists and not yet monopolized and conglomerated by businesspeople.”

Today, reporters in Turkey face limited resources paired with immense pressure from the government and the constant threat of SLAPP lawsuits that are used to silence them. The few remaining independent media outlets are also far from being an oasis for journalists.

“We see that the critical media, just like pro-government outlets, are often unable to produce long research and investigative dossiers,” Ertuna notes. “They stick to routine news. Sometimes this is due to lack of resources, other times it’s due to practices of punishment, restriction, and obstruction.”

He argues that modern-day media outlets in Turkey have become institutions that no longer aim to make a profit, but rather serve as instruments for the interests of large conglomerates in other business fields, and to negotiate with the ruling powers and defend their interests. “In such a political economy, the possibilities of practicing Uğur Mumcu-style journalism in the mainstream media has been a hard task,” Ertuna adds.

A journalism training seminar at um:ag. Image: Courtesy of um:ag

That environment has made um:ag’s role even more crucial in recent years: Teaching a type of journalism that is rapidly disappearing from the mainstream media landscape, and only finds its way into independent media in exceptional cases. In practice, it means teaching young reporters how to read hundreds of pages of judicial cases, public reports, and statements in order to find clues hidden between the lines; showing them how to meticulously collect and archive evidence; how to talk to those on all sides of a story; and how to leave a clear structure for others to continue an investigation.

And um:ag, a GIJN member since 2018, does more than just training journalists. For more than 25 years, it has been creating a space for people to express their creativity with seminars in fields like writing, philosophy, and cinema, providing what the organization calls a “lifelong education.”

The foundation also keeps publishing new editions of Uğur Mumcu’s work. “Even though these are old stories, investigative files that are thought to shed light on a certain period in Turkey, I think that all of these books are a valuable resource, a standard text for anyone who wants to do investigative journalism,” says Ertuna.

Uğur Mumcu’s daughter, Özge Mumcu, co-founded um:ag to continue her father’s legacy. Image: Courtesy of Mumcu

“Today, no matter which of my father’s books you open, you can find traces of an issue that is current in Turkey now,” says Özge Mumcu, adding that the foundation strives to remain independent to carry out their activities. But this is not an easy task in a country with a faltering economy. When asked about the biggest challenge that um:ag faces, Özge Mumcu doesn’t hesitate. “It’s financial difficulties.”

“Personnel costs, heating, maintenance of the building, paper costs of publishing the books… We are in the red on many items,” she explains. “With the economic crisis on top of all that, we are finding it difficult to turn the foundation around financially. That is why we call for donations from time to time.”

Apart from the donations, the foundation is funded by royalties from Uğur Mumcu’s books and the income from their seminars.

Despite all the difficulties, Özge Mumcu is determined to carry on her father’s ideals and further his legacy — to make um:ag a place where investigative journalists can come to work, collaborate, and conduct investigations that hold the powerful to account.

Additional Resources

Editor’s Pick: 2021’s Best Investigative and Data Stories from Turkey

When Media Capture Backfires: Local Elections and Digital Media in Turkey

How Turkey Silences Journalists Online, One Removal Request at a Time

Serdar Vardar is an investigative journalist with a political science degree from the University of Buenos Aires. After living more than a decade in South America he moved to Germany to cover Turkey and global environmental stories for Deutsche Welle. Vardar was part of ICIJ’s global Pandora Papers and Shadow Diplomats investigations.

Serdar Vardar is an investigative journalist with a political science degree from the University of Buenos Aires. After living more than a decade in South America he moved to Germany to cover Turkey and global environmental stories for Deutsche Welle. Vardar was part of ICIJ’s global Pandora Papers and Shadow Diplomats investigations.

The post Uğur Mumcu: The Foundation Continuing the Legacy of an Assassinated Turkish Investigative Reporter appeared first on Global Investigative Journalism Network.

1 year ago

70

1 year ago

70