The solar energy sector is big and getting bigger. That’s a really good thing given the central role we expect and need solar to play in a just transition away from fossil fuels.

But solar’s growth, especially in large arrays, has made it much more visible in communities and landscapes across the country, sparking a lot of conversations about land use, technology options, community engagement, and how best to site the many more megawatts of solar we need.

That’s why it’s great to have a new “collaboration agreement” on large-scale solar, the result of a multi-year effort with scores of experts, nonprofit groups, and solar developers to address issues of siting and technological considerations in the hopes of developing a set of best practices. The agreement, which the Union of Concerned Scientists is a party to, is part of an “Uncommon Dialogue” sponsored by Stanford University that aims to both accelerate large-scale solar in the United States while “simultaneously addressing conservation and community opportunities and challenges.”

Climate, conservation, community

Working on this project has powerfully reminded me how much has changed since I started in the solar energy field more than three decades ago. Back then, my focus was on small (really small) systems, measured in tens of watts. At that time, even the largest solar arrays in the world measured only in the hundreds of kilowatts, enough to generate the equivalent of the electricity needs of just a few tens of thousands of US households. I can distinctly remember how wacky it seemed when I first heard someone propose a one-megawatt (1000-kilowatt) solar array.

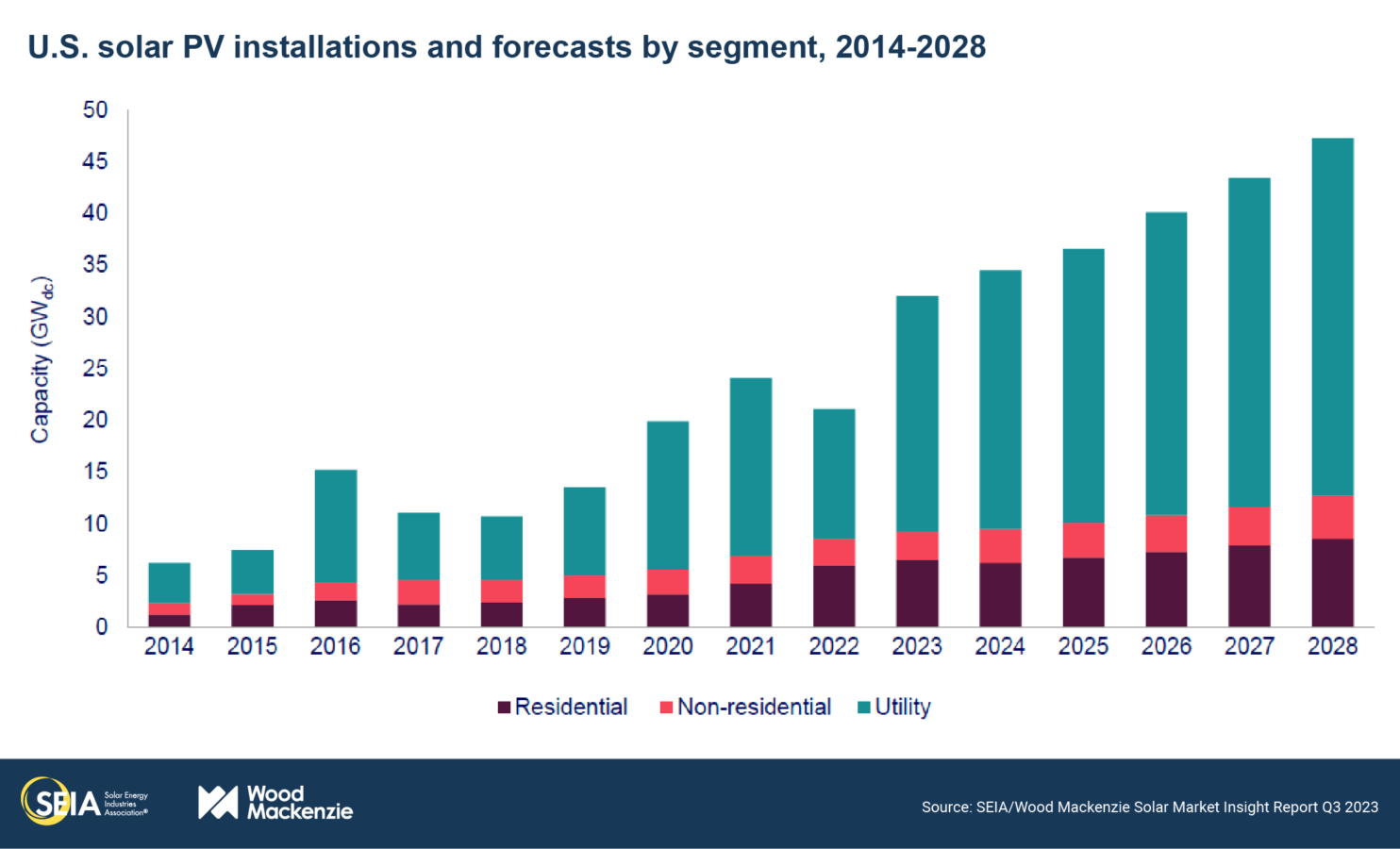

We’ve come a very long way since then: solar costs have come down, solar panels have gotten more efficient, solar arrays and solar farms have gotten much bigger, and solar has grown to be a noticeable piece of US electricity supply. Instead of the 50 watts that was standard in my early days, solar panels now commonly exceed 300 watts each. Single projects can be hundreds of megawatts. Last year, solar accounted for almost 5 percent of US electricity. The industry is projecting the US sector to grow by 32,000 megawatts this year—50 percent more than in 2022, and enough to increase solar’s portion of the US electricity supply to well more than 6 percent.

Rooftop solar is an important piece of the sector’s success. Solar systems now grace the roofs of more than four million US households, institutions, and businesses. Onsite solar allows people to generate electricity right where it’s needed, and, when combined with batteries, it offers reliable backup power.

But solar also has the advantage of being deployable at a range of scales, and that range is another key to solar’s success. And, it turns out, most of solar’s megawatts—both current and projected—are in large-scale systems: in fields, on landfills, or in deserts. Larger systems offer greater economies of scale, and with the ability to optimize performance in terms of orientation and tilt, for example, they can offer increased energy production. Those factors combine to make large solar a very attractive prospect, one that potentially offers the lowest costs for customers.

This graph depicts actual growth in solar installations since 2014 and projections for further growth in the next five years. (GW = gigawatts = 1000 megawatts; utility = large-scale)

This graph depicts actual growth in solar installations since 2014 and projections for further growth in the next five years. (GW = gigawatts = 1000 megawatts; utility = large-scale)The challenge lies in finding sites that work. A site of course needs to offer good sun and the right terrain and access to transmission lines to get the electricity to market at a reasonable cost. But successful siting also needs to take into account other aspects of the environment, such as: whether the land is currently used for crops or grazing, covered with trees, or part of a fragile desert ecosystem. And good siting must also consider the needs and wishes of people nearby—tribal communities, farmers, or other residents, for example.

Hence this uncommon dialogue effort, led by Stanford, the Nature Conservancy, and the Solar Energy Industries Association, to bring together a wide range of stakeholders. Those stakeholders have included solar developers and investors, land conservation and environmental non-profit organizations, tribal nation representatives, agricultural interests, environmental justice and community groups, and government agencies.

Finding common ground through uncommon dialogue

The effort spotlighted some important realities of where we stand today in solar’s development. For example, the United States added more than 20,000 megawatts of solar energy to the grid in 2022—making up more than half of all new electricity capacity that year. By 2033, forecasts cited by the group suggest solar energy will grow to at least 700,000 megawatts of capacity “assuming no new major policy hurdles or commercial challenges”—more than a fivefold increase over today’s US solar deployment.

As for the land implications, the agreement cites the US Department of Energy’s Solar Futures Study, which suggested that a buildout of solar commensurate with the need and the opportunity could involve siting on some 10 million acres, meaning 0.5% to 0.6% of the land area of the contiguous United States. That’s a good deal of land, but it’s notably much less land than is used for, say, livestock grazing or feed production, oil and gas leasing on federal lands, or even for growing corn to make ethanol.

Given the land implications, this new agreement offers suggestions about the best areas for exploration and investment of time and resources to help maximize benefits and minimize conflicts. In particular, the participants identified six areas where working groups might constructively go much deeper in addressing issues and opportunities: community and stakeholder engagement, siting-related risk assessment and decisionmaking, energy and agricultural technologies, information tools, tribal relations, and policy solutions. The idea is to “create best practices that solar companies, local governments, and other stakeholders can use to effectively site solar projects.”

Along with helping to shape the agreement, I was involved in the technologies subgroup, which looked at how technological advances could be brought to bear—specifically, how research, development, demonstration, and deployment of energy and agricultural technologies and practices could help “to advance large-scale solar development while also protecting important working and natural lands.” That group considered, for example, different approaches to integrating solar into a landscape, through “dual-use” solar and agricultural approaches (“agrivoltaics”) or siting on former mining sites (“brightfields”). And it proposed having a greater focus on identifying ways to build and operate solar arrays that offer conservation/ecological and agricultural benefits such as healthier soil.

The agreement, after more than a year and a half of dialogue, offers a launching point for that working group as well as the others to continue their work, and a call for additional parties who might be interested in engaging in one or more of those groups.

Finding the best way forward

Solar is different from the technologies that have dominated our power systems for many decades. Other energy development, in this country and elsewhere, has most often gotten it wrong with respect to local communities and the environment, not to mention climate change. For example, think of the siting of fossil fuel plant smokestacks and their pollution that disproportionately affects Black and Brown neighborhoods, or the many landscapes (and communities) ruined by fuel extraction. With solar, there are no smokestacks, no fuel extraction. Large-scale solar has a chance to be a shining star when it comes to fitting into the landscape too, to avoid perpetuating the injustices of the power sector with strong stakeholder engagement and good siting.

Solar’s growth from my early days in the sector—and particularly in recent years—has led to less power plant pollution. It has also helped to diversify our electricity sources, created more reliable electricity grids, while stabilizing and increasingly lowering electricity costs. Figuring out how to get more solar power in the best way possible—with due consideration of climate, conservation, and community—is very much in our collective best interest. This agreement marks an important step in the right direction.

Related UCS materials:

- Can California Cropland Be Repurposed for Community Solar?

- Where is California Going to Site Its New Solar Power?

- How Much Land Would it Require to Get Most of Our Electricity from Wind and Solar?

- Solar Panels Should Be Reused and Recycled. Here’s How.

- Progress Continues for US Residential Solar: Reviewing the Latest Numbers

- Solar Energy’s Latest Record Breaker: 5 Takeaways

- Climate Justice and the Debate about Community Solar on Farmland

1 year ago

65

1 year ago

65