Whales could always speak for themselves. Humans just didn’t hear them.

Roger Payne changed that with a simple, empathetic act: He listened. And then we all did.

In 1970, Payne (1935-2023) made sure the world finally paid attention to the “Songs of the Humpback Whale.” Payne’s landmark 35-minute album of recorded whale song in the wild deepened humanity’s connection with the natural world, catalyzed the global movement to stop commercial whaling, and had a lasting impact on the growing ecology movement, including Greenpeace.

Payne, who passed away in June at age 88 at his home in Vermont, founded Ocean Alliance in 1971 and was an inspiration and friend to Greenpeace activists during and far beyond the iconic “Save The Whales” campaign that garnered international in the 1970s and played a key role in the adoption of an commercial whaling moratorium in 1986.

Born in New York City, educated at Harvard and Cornell, Payne’s pioneering whale song recordings and decades of study of their communications have arguably done more to dispel the Moby Dick myth of the violent and solitary whale than anything else. His first record of what he described as an “exuberant, uninterrupted rivers of sound,” made with the help of researcher Scott McVay, would go on to sell more than 100,000 copies, making it the bestselling environmental album of all time.

“My idea was, if you can move people emotionally, you can also get them to act,” Payne told Nautilus in 2021. “To see if I was right, I started playing humpback whale sounds to friends and other small audiences, and soon it became very clear that these sounds moved people deeply. In fact, some friends wept when they heard them—they’re that powerful.”

A humpback whale and calf (megaptera novaeangliae) are in the South Pacific Ocean.

©Doug Perrine/Seapics.com © Doug Perrine / SeaPics.com

A humpback whale and calf (megaptera novaeangliae) are in the South Pacific Ocean.

©Doug Perrine/Seapics.com © Doug Perrine / SeaPics.com‘A tool to bring whales into everyone’s living rooms’

Among those deeply moved by Payne’s recordings were present and future Greenpeace activists, including Rémi Parmentier. A founding member of Greenpeace International and campaigner aboard the Rainbow Warrior during the anti-whaling voyages of the 1970s and early 1980s, Parmentier recalls Payne’s first album of whale song being a part of his welcome package.

“When I joined in 1976 the international campaign to protect whales, I was given a cardboard box filled with documents and books for my induction,” Parmentier recalls. “Among them was Roger Payne’s record ‘Songs of the Humpback Whale’ which had been released in 1970 in the U.S., but which had never been marketed in France (and probably not in the rest of Europe either, except maybe a few dozen copies in some rare vintage record shops in London). After listening to whale sounds for the first time I understood how powerful the record was as a tool to bring whales into everyone’s living rooms.”

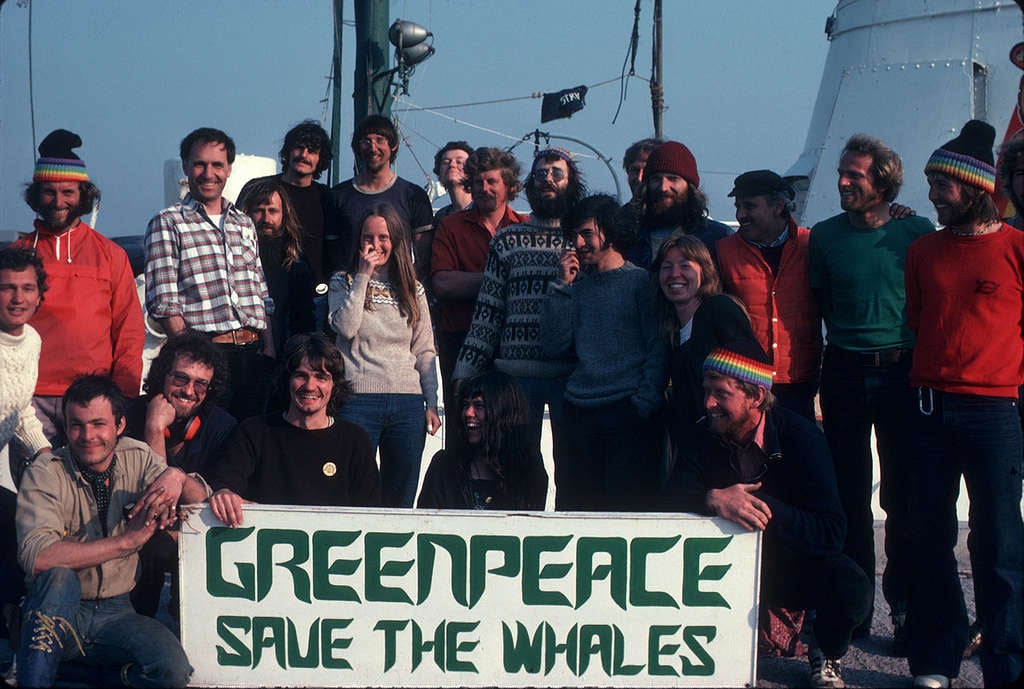

Rainbow Warrior crew holding banner “Save the Whales”. © Greenpeace / Jean Paul Ferrero

Rainbow Warrior crew holding banner “Save the Whales”. © Greenpeace / Jean Paul FerreroNot only was Parmentier personally moved by Payne’s recording, but he quickly became committed to widening its audience.

“So, each time I was invited by a radio station to speak about our campaign for a moratorium on commercial whaling, I’d carry under my arm my copy of Roger Payne’s record, and it blew the journalists’ minds and their audience’s. Just after we bought the Rainbow Warrior in 1977, ready to set sail in 1978 to stop whaling fleets in the Atlantic Ocean, I called the CEO of the French subsidiary of Capitol Records and proposed that they release the record in France,” Parmentier says.

“Maxime Schmitt was his name and I was lucky that he espoused the project wholeheartedly. He asked me to write in French the cover, back cover and a leaflet which was inserted inside the record envelope, featuring Greenpeace and the Rainbow Warrior mission to ban commercial whaling. Dozens of thousands copies were sold in French record shops and on the Greenpeace-France merchandise catalogue in 1978 and in the following years.”

For Parmentier, the release and impact of the record remains a key part of the whaling campaign — as does Payne.

“The record was reprinted time and time again as a key campaign icon, until finally, the International Whaling Commission gave us reason in 1982 and endorsed the proposed moratorium on commercial whaling,” he remembers. “Roger Payne was present at that meeting of the International Whaling Commission, and I remember we celebrated together that evening after the vote was passed.”

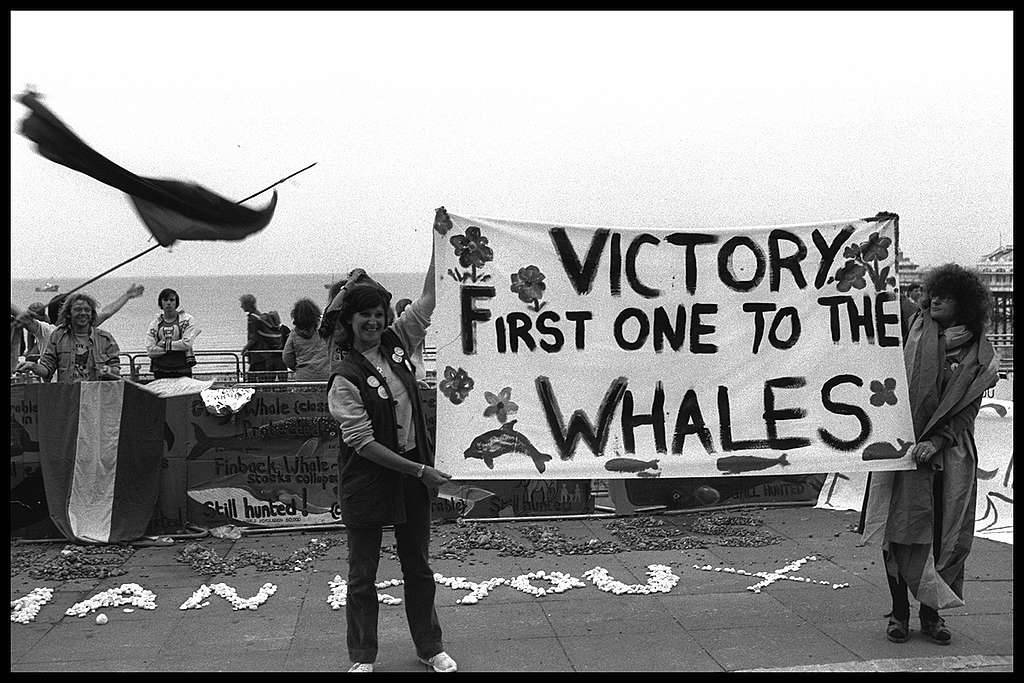

Greenpeace activists holding banner that reads: ‘Victory First One To The Whales’, on the floor mussels read the words: ‘Thank You’, Brighton, UK. Demonstration outside the International Whaling Commission Meeting held in Brighton. © Greenpeace / Pierre Gleizes

Greenpeace activists holding banner that reads: ‘Victory First One To The Whales’, on the floor mussels read the words: ‘Thank You’, Brighton, UK. Demonstration outside the International Whaling Commission Meeting held in Brighton. © Greenpeace / Pierre Gleizes‘Roger made me feel like I was doing incredibly important work’

It wasn’t just the sounds of whales that caught Payne’s attentive ear. His willingness to listen to those humans, like Kelly Rigg, who asked for his help also made him a beloved figure in the environmental movement for decades. Rigg, who started her Greenpeace journey in 1982 with Greenpeace USA campaigning against offshore oil drilling, recalls initially reaching out to Payne and being uncertain if she’d even hear back.

“Our relationship began when I was just starting at Greenpeace, coordinating a campaign to save Georges Bank from offshore oil and gas development,” Rigg says. “This region is home to the North Atlantic right whale, which is highly endangered (there are only about 350 of them left). Roger was living in Massachusetts at the time so knew the area well although his studies were focused on the southern right whale population.

“I got in touch with him, not knowing if this extremely well-known person would even take a call from a junior campaigner, but he did and I got him to come testify at a local hearing in which he made a very compelling case about the similarities in geography between Cape Cod and the area he was studying, and why drilling there would be a very bad idea.”

Humpback whale off the Atlantic coast. US. © Greenpeace / Pierre Gleizes

Humpback whale off the Atlantic coast. US. © Greenpeace / Pierre GleizesIn her 20 years at Greenpeace, Rigg’s work included leading the international campaign to save Antarctica and establishing the World Park Base on the ice. She would go on to serve as Executive Director of the Global Call for Climate Action, coordinate the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, and is the founding director of The Varda Group. All these years later, after working with so many colleagues on so many campaigns, she still holds Payne in high esteem — and still treasures the way that he showed her the utmost respect from the very beginning.

“You know that old saying that you may not remember what a person said or did, but that you remember how he made you feel? As a very young campaigner, Roger made me feel like I was doing incredibly important work, and I always loved him for that,” Riggs says.

Active Listening

At Greenpeace, we have, over the years, talked about the importance of giving the fragile earth a voice. But thanks to Roger Payne, we have a poignant reminder that the earth can often speak for itself.

We just have to listen.

1 year ago

80

1 year ago

80

6 of 9

6 of 9 Schmitt asked me to write in French the cover, back cover & a leaflet which was inserted inside the record envelope, featuring the Greenpeace Rainbow Warrior mission to save the whales. It became a blockbuster in French record shops & on the Greenpeace-France catalogue.

Schmitt asked me to write in French the cover, back cover & a leaflet which was inserted inside the record envelope, featuring the Greenpeace Rainbow Warrior mission to save the whales. It became a blockbuster in French record shops & on the Greenpeace-France catalogue.