Solomon Pili Kahoʻohalahala, known as Uncle Sol, is a member of the Greenpeace International delegation at the International Seabed Authority (ISA) meeting in Jamaica, where governments are gathering to decide the future of deep sea mining. Hawaii is one of the closest territories to the Clarion-Clipperton Zone where the industry is proposing the first ever deep sea mining site. In this blog, Uncle Sol explains why the representation of Indigenous People at the ISA meeting matters.

Government officials have been meeting here in Kingston, Jamaica three times a year to talk about deep sea mining and they are finally realising something that they have never ever contemplated: the connection of people to the deep sea.

At these meetings, governments are seeking to create regulations for deep sea mining which will destroy a place that’s not just the home of Indigenous People of the Pacific, like me, but the place of our creation.

In our culture, there is no separation between us and nature – it is who we are. No matter where we are in the deepest part of the ocean, the surface of the waters, to the land and the mountains and the sky; we are part of all of it. So when industries are plotting to destroy the area of creation and have no regard for that part of our identity, it hurts.

Uncle Sol (center) and Phil McCabe, the DSCC Pacific coordinator, in Kingston, Jamaica for the 28th Session of the International Seabed Authority in March 2023. © Martin Katz / Greenpeace

Uncle Sol (center) and Phil McCabe, the DSCC Pacific coordinator, in Kingston, Jamaica for the 28th Session of the International Seabed Authority in March 2023. © Martin Katz / GreenpeaceThe Metals Company is pushing to apply for a commercial license in the waters adjacent to Hawaii despite so many unresolved issues and no final regulations in clear sight. When I challenged The Metals Company on the absence of cultural considerations in their deep sea mining proposal presentation, they answered that they hadn’t considered it prior to me coming to the ISA. They say they now plan to address this issue, but still do not know how to do so.

That’s why having a seat at the table at negotiations here in Jamaica is important to me. Indigenous knowledge and perspectives have been shut out of negotiations for too long – they should be recognised and we should have the power to influence decisions that directly affect us. This is what environmental justice means to me.

In March 2024, my third time attending an ISA meeting, I could sense that more leaders are recognising the importance of our voices. At the start of the meeting, I asked global leaders to join me in chanting to welcome my ancestors, my Kūpuna, into the room to give me comfort and guidance in a space where important decisions are being made. It gave delegates a chance to think about their ancestors who they’ve inherited the world from, and many representatives told me they appreciated the symbol of respect and cultural practice that they hadn’t experienced before.

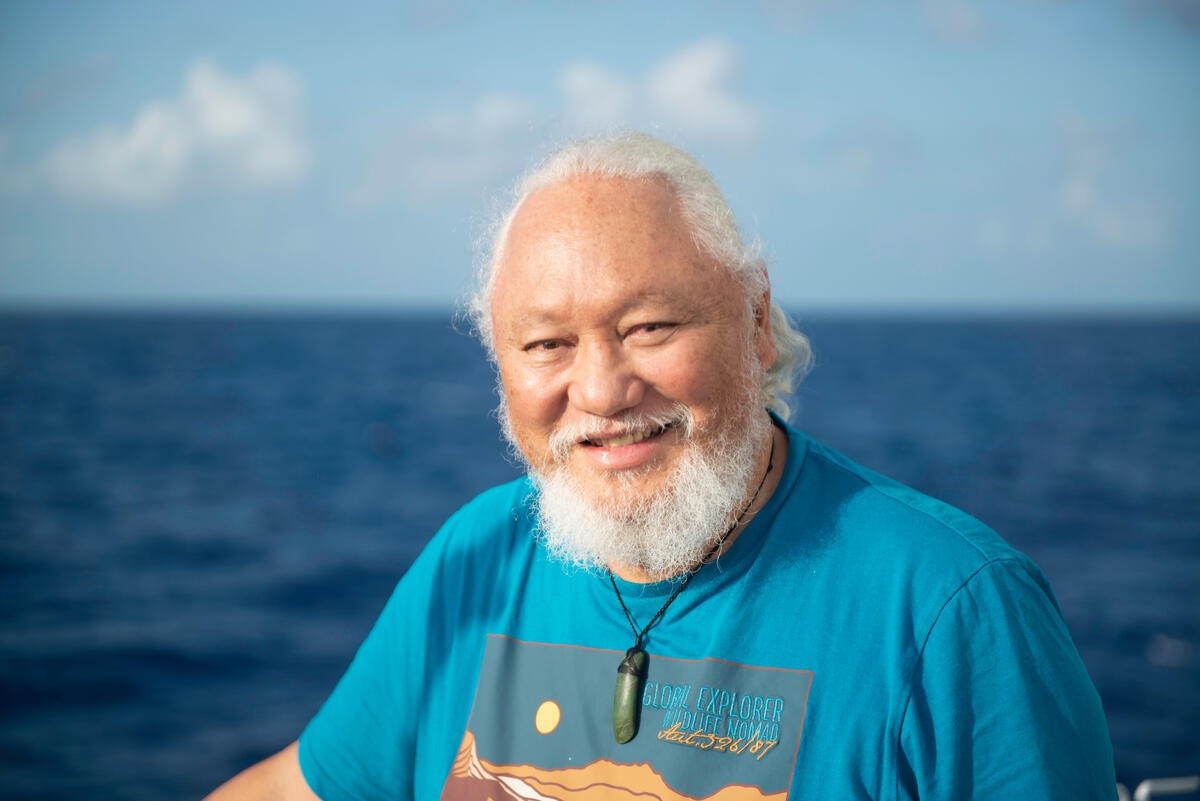

Uncle Sol aboard the Arctic Sunrise, on the day before arrival in Kingston, Jamaica

Uncle Sol aboard the Arctic Sunrise, on the day before arrival in Kingston, Jamaicafor the 28th Session of the International Seabed Authority in March 2023. © Martin Katz / Greenpeace

We are not just here to be participants, we are here because we carry responsibility to protect our world for future generations. Indigenous People of the Pacific have been defending the oceans for centuries and hold the key to protecting it for future generations, just like my Kūpuna have protected it for me. I want my three-month old great grandson, Waioipohapauea, to grow up in a world where he has the same enjoyment, benefits and sustenance that we have had in our generation and past ones.

If there is true inclusion of Indigenous voices at global negotiations, then I feel optimistic about the future – and I need to be positive to fulfill my commitment to be inspired to continue campaigning for a better world for little Waioipohapauea.

7 months ago

88

7 months ago

88