Ever wondered who’s behind the ads you see on websites and apps? ProPublica national reporter Craig Silverman has carved out an investigative niche trying to answer that very question.

Ads for a brand appearing in an unlikely or controversial place could be the start of a story.This year alone, Silverman’s investigations in digital advertising have yielded stories on right-wing websites running ads containing fake celebrity endorsements and sites collecting ad revenue from Google despite violating its advertising policies .

Global internet advertising revenue is forecast to reach $723.6 billion in 2026. A lot of money is changing hands in a system that can be difficult to understand or deliberately opaque. Digital advertising is rife with fraud, scams, waste and deception, Silverman told attendees at the at the 13th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (#GIJC23). “People need to look into it,” Silverman said. “The way the system has been designed allows people to hide and allows money to flow into places it shouldn’t be.”

Know Your Digital Ads

Understanding the different types of online advertising and the different business relationships involved is a good starting point. Banner ads on websites or ads within the copy of an article on a news site are likely to be programmatic ads. With these ads, brands are buying access to an audience, rather than the prestige of being featured in a particular publication.

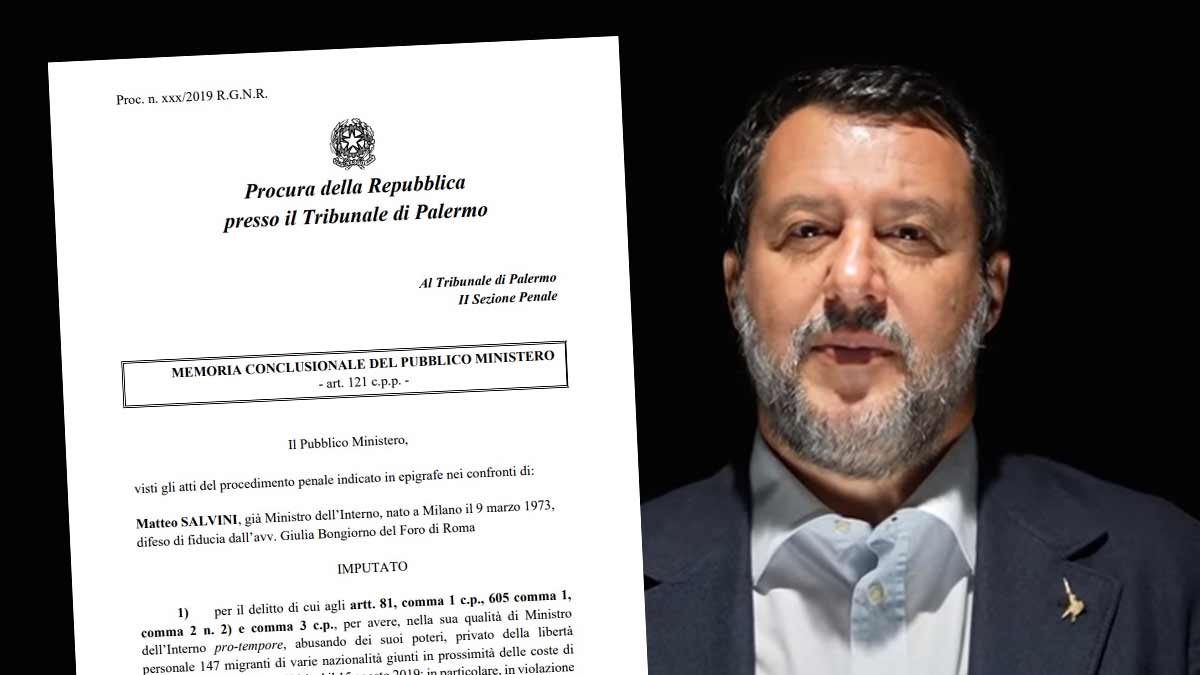

Craig Silverman is national reporter for ProPublica. Previously, he was media editor at BuzzFeed and the head of BuzzFeed’s Canadian division. Image: Wikipedia, Creative Commons

The sale of programmatic ads happens in milliseconds, meaning brands may have no idea where their ads appear. “If you’re spending a decent amount of money you could be appearing on thousands and thousands of apps or websites,” he explained. Ads for a brand appearing in an unlikely or controversial place could be the start of a story.

Native or content advertising, frequently served through platforms such as Taboola or Outbrain, refers to the often clickbait content that is advertised at the end of online articles. For these ads, money only changes hands when a website user clicks on the content.

You can gather a fair amount of information within seconds of looking at an ad on a page, said Silverman. Display ads typically have a triangle symbol marked AdChoices or an information icon that can show you what ad network or platform has placed the ad. Native ads will likely display a logo that indicates which platform is involved.

For direct advertising (ads that come directly from a brand) and affiliate ads (where a third-party receives commission for sales or clicks on the links it promotes) hover over the ad and inspect the URL it links to. This will also help you detect if it’s programmatic, for example if it features Google in the URL.

Understand Affiliates

There are lots of scams running through affiliate advertising including for false healthcare products and services, explained Silverman. Each affiliate has an ID number, typically shown in the link from the affiliate ad — sometimes you can spot these in the URLs of direct ads too, meaning it has been sold by an affiliate. This will help you to keep track of the affiliates involved in a deal or scam.

Journalists can use Affbank or ClickBank to see the different products being offered to affiliate marketers, including ads for false healthcare claims or crypto schemes.

Delve Into Ads.txt

Ad libraries on Meta, Google, and TikTok are a treasure trove for investigative journalists.Ads.txt is a text file that publishers host on their servers listing the other organizations authorized to sell their products or services. It’s also a voluntary industry standard and ad platforms like Google are not supposed to work with sites that don’t use ads.txt.

It can be found by adding “ads.txt” to the domain name of a website. A publisher’s ads.txt file gives you details on the nature of an advertiser’s relationship with a publisher, for example whether they are a direct advertiser or reselling ads on behalf of someone else. Each of these links in the advertising chain will have their own ID.

Ad networks are supposed to publish their own list of advertisers too, and these details should match those listed by publishers in their ads.txt files. If there are discrepancies between these two lists, it could be a lead, said Silverman. For example, scammers have stolen ad revenue from publishers by pretending to be the Guardian and Financial Times on ad networks.

The site Well-Known presents ads.txt data in a simplified, more structured form and allows journalists with a free account to search advertising data for other examples of seller and advertiser IDs. It’s a good way to map out who a publisher or advertiser is working with to earn money and any apps or other sites run by them. “It’s a window into their business model,” said Silverman, who shared more examples of how to use Well-Known in his workshop.

Study Ad Platforms’ Policies

“You need to be systematically looking at these [ad] libraries and running searches… An ad may run for just a day.” — ProPublica’s Craig SilvermanFamiliarity with the advertising rules of Meta, Google, and TikTok will help you identify ads that shouldn’t be appearing, said Silverman. Google, for example, has specific rules about specific content it should not be placing ads next to, including false claims about climate, health, and elections.

ProPublica has published several stories based on violations of ad platforms policies, including identifying websites making ad revenue from websites publishing false COVID-19 claims.

Check Out Ad Libraries

Ad libraries on Meta, Google, and TikTok are a treasure trove for investigative journalists. They are searchable databases of ads run on these platforms. In compliance with platforms’ transparency commitments, political and social issues ads are likely to be archived for longer periods – as long as seven years in some cases — with more targeting data available in the library.

Other ads may disappear from ad libraries as soon as a campaign stops. “You need to be systematically looking at these libraries and running searches,” recommended Silverman. “An ad may run for just a day.”

Meta’s ad library allows you to filter ads by country and ad category (such as political advertising), and to search by keyword. The search works across both Instagram and Facebook ads. Google’s ad library doesn’t allow keyword searches, but will return results for image, text, and video ads. The results are limited to verified advertisers, however, which is a voluntary process. “Anyone who is sketchy will not go through this,” said Silverman, so it won’t appear in the library.

TikTok’s policy says it doesn’t accept political ads, but there have been instances of influencers receiving money from political groups to promote messages. Its ad database is searchable by keyword. The platform also offers useful tools aimed at marketers that journalists can use to view trending or popular ads by country or topic.

More Tools

- Adbeat: helps you see the ads being run by and on websites (limited free version). Note: It has a US and Western bias.

- Blacklight: from The Markup can show the ad tracking running on a website.

- Adalytics.io and Checkmyads.org: Research website Analytics and advocacy site Checkmyads run their own investigations into digital advertising and share tools and data on the market.

10 months ago

51

10 months ago

51