Five years ago, bulldozers with chains cleared forests and woodlands almost triple the size of the Australian Capital Territory in a single year.

Brazil? Indonesia? No – much closer: Queensland. In 2018-19, truly staggering land clearing, mostly by farmers and cattle graziers, saw around 680,000 hectares of habitat destroyed – more than the preceding 18 years. Even though the state Labor government tightened land clearing rules in 2015, the new rules were riddled with loopholes. If Queensland was a country, it would have been the ninth highest forest destroying nation globally in 2019 – just above China.

Clearing is slowing – but nowhere near fast enough. At the end of 2022, Queensland quietly released its latest figures, showing clearing rates in 2019-20 had fallen to under two Australian Capital Territories that year (around 418,000 hectares). The government celebrated it as a win, as did some farming groups. But it’s nothing to be celebrated.

Yes, it’s better than the worst year in the last two decades. But as our climate and extinction crises worsen and as the Great Barrier Reef teeters on the brink, clearing as usual is no longer good enough.

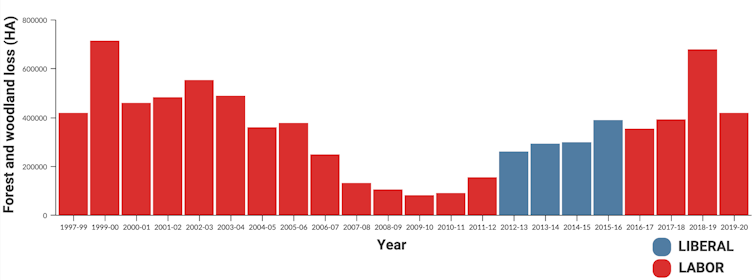

Queensland’s historical forest and woodland clearing rates by political party in power.

Queensland’s historical forest and woodland clearing rates by political party in power.

Why is Queensland still clearing so much – and why does it matter?

In a word, beef. Like Brazil, Queensland tears down its forests and woodlands largely to make way for grass to feed livestock – mainly cattle. The latest 2019-20 figures show 85% of all clearing was done to create new pasture.

You might have heard defenders of land clearing claiming the land being cleared is home to low-value vegetation or trees that regrow easily, such as mulga acacia. This is not true. About 52% of all vegetation cleared in 2019-20 was classified as old growth or older than 15 years. The Brigalow Belt and the Mulga Lands accounted for three-quarters of all clearing. Of the clearing in these regions, 80% was full clearing, meaning bulldozing turned forests or woodlands into areas with less than 10% canopy remaining.

Nature is forced to give up habitat so cattle have grass to eat.

Shutterstock

Nature is forced to give up habitat so cattle have grass to eat.

Shutterstock

This matters, because Queenslanders are the custodians of more biodiversity than any other Australian state, most of which is found in its woodlands and forests.

Queensland’s thousands of unique plant species provide homes and resources for many of Australia’s famous animals. More than 1,800 species of Australian plants and animals are now threatened with extinction – and Queensland’s land clearing is a key threat for many.

It can be hard to connect bulldozers clearing trees and the reality of what it does to the animals relying on them. So we cross-referenced the cleared land with threatened species distribution maps. Approximately 417 threatened species lost some of their habitat, with the worst hit including grey falcon, the newly endangered koala, and squatter pigeon. The clearing is a double blow, as many of these species were devastated by the Black Summer fires.

Read more: Repairing gullies: the quickest way to improve Great Barrier Reef water quality

This large scale destruction also hampers Australia’s ability to meet climate targets. The agriculture, forestry and other land use sector on average, accounted for almost a quarter (23%) of the world’s human-caused emissions. Of these, 45% were from deforestation.

If we leave woodlands and forests intact, they look after our interests too. They improve water quality and availability for our uses and for nature. They control erosion by protecting soils and riverbanks. And they increase the productivity of nearby cropland by hosting pollinators and species which prey on plant pests. Ripping out the forests and woodlands not only reduces the carbon they sequester but also makes the ground immediately warmer, making many parts of Queensland even hotter and more drought prone.

Native vegetation cleared for pasture near Maryborough.

Martin Taylor

Native vegetation cleared for pasture near Maryborough.

Martin Taylor

Destroying old, biologically important woodland and forests at such scale is a terrible idea. It flies in the face of global pledges to end deforestation and maintain the integrity of all of Earth’s ecosystems. Australia is a signatory to both of these.

Cynics might wonder whether the rush to clear pasture is linked to the fact many of our trading partners are looking to import beef not linked to deforestation. In December, the European Union passed laws requiring beef exporters to show their operations haven’t contributed to deforestation. Cattle must not have been raised on land cleared after December 2020. Though the EU is not the largest beef market for Australian farmers, the National Farmers Federation reacted angrily.

Even in Australia, huge companies such as Woolworths and McDonalds have committed to remove deforestation from their supply chains.

Some companies are doing the right thing, but the sheer scale of felling and clearing shows many are not. Both the Queensland and federal governments must fix the problem with better regulation and adequate enforcement, access to data to demonstrate deforestation-free credentials, and incentives for producers to improve their land use to the emerging global standards. In the age of ubiquitous satellite imagery, it’s impossible to hide what you’re doing. One option could be to make the deforestation images publicly available in real time.

Brigalow forest cleared for pastures Central Queensland. Credit Martine Maron.

Brigalow forest cleared for pastures Central Queensland. Credit Martine Maron.

Labor has pledged action federally – but the state Labor government must do more

There’s a strange disconnect developing where Labor, federally, has signalled they want to reverse Australia’s biodiversity crisis, while at state level, their actions are nowhere near enough. Federal Labor recently signed national and international commitments aimed at halting species extinctions, reversing biodiversity loss, and stopping further land degradation. For that to actually happen, though, it will need the states to play ball – especially Queensland.

Lopper removing tree by tree in koala habitat for housing in Springfield Qld. Credit Martin Taylor.

Lopper removing tree by tree in koala habitat for housing in Springfield Qld. Credit Martin Taylor.

Why is Queensland ground-zero for deforestation in Australia? It has water, arable land, and a decentralised population often reliant on farming or mining work outside the major cities. Sugarcane plantations, mango farms, beef cattle, dairy, bananas – it’s hard to shift a long-set path.

But if the state government is unable to close the obvious loopholes such as Queensland’s questionable land clearing Category X and stop rampant land clearing, the environmental, social and economic bill will come due. Extinctions, coral death, climate damages, degraded human health and the reputational risk of becoming a pariah.

It doesn’t have to be that way. By working with farmers and graziers, they can end the policy ping-pong with laws to encourage all food producers to shift to deforestation-free produce. We can get there.

Read more: EcoCheck: can the Brigalow Belt bounce back?

Michelle Ward received PhD funding from the Federal Government. Michelle also works for WWF as a Conservation Scientist.

James Watson has received funding from the Australian Research Council and National Environmental Science Program and receives funding from South Australia's Department of Environment and Water. He serves on scientific committees for Bush Heritage Australia, SUBAK Australia, BirdLife Australia and has a long-term scientific relationship with the Wildlife Conservation Society. He serves on the Queensland Government's Land Restoration Fund's Investment Panel.

1 year ago

85

1 year ago

85